Did UK energy companies pull a LIBOR?

UK regulators are investigating claims that energy companies in Britain have rigged wholesale gas prices similar to the way banks manipulated the London interbank offered rate (LIBOR) to their own advantage.

UK regulators are investigating claims that energy companies in Britain have rigged wholesale gas prices similar to the way banks manipulated the London interbank offered rate (LIBOR) to their own advantage.

On Sept. 28, energy reporter Seth Freedman noted something strange. Freedman, who works for ICIS Heren, which publishes energy reports upon which suppliers base wholesale prices, realized that dealers were making unrealistic bids. They appeared to manipulate the closing price to suit their own trading positions. Sept. 28 wasn’t any ordinary day either. It marks the end of the gas financial year and heavily affects future prices.

The UK’s Financial Services Authority (FSA) and Ofgem, which regulates the electricity and gas markets in the UK, were alerted and are investigating. Today Energy Secretary Ed Davey is expected to make a statement in the House of Commons.

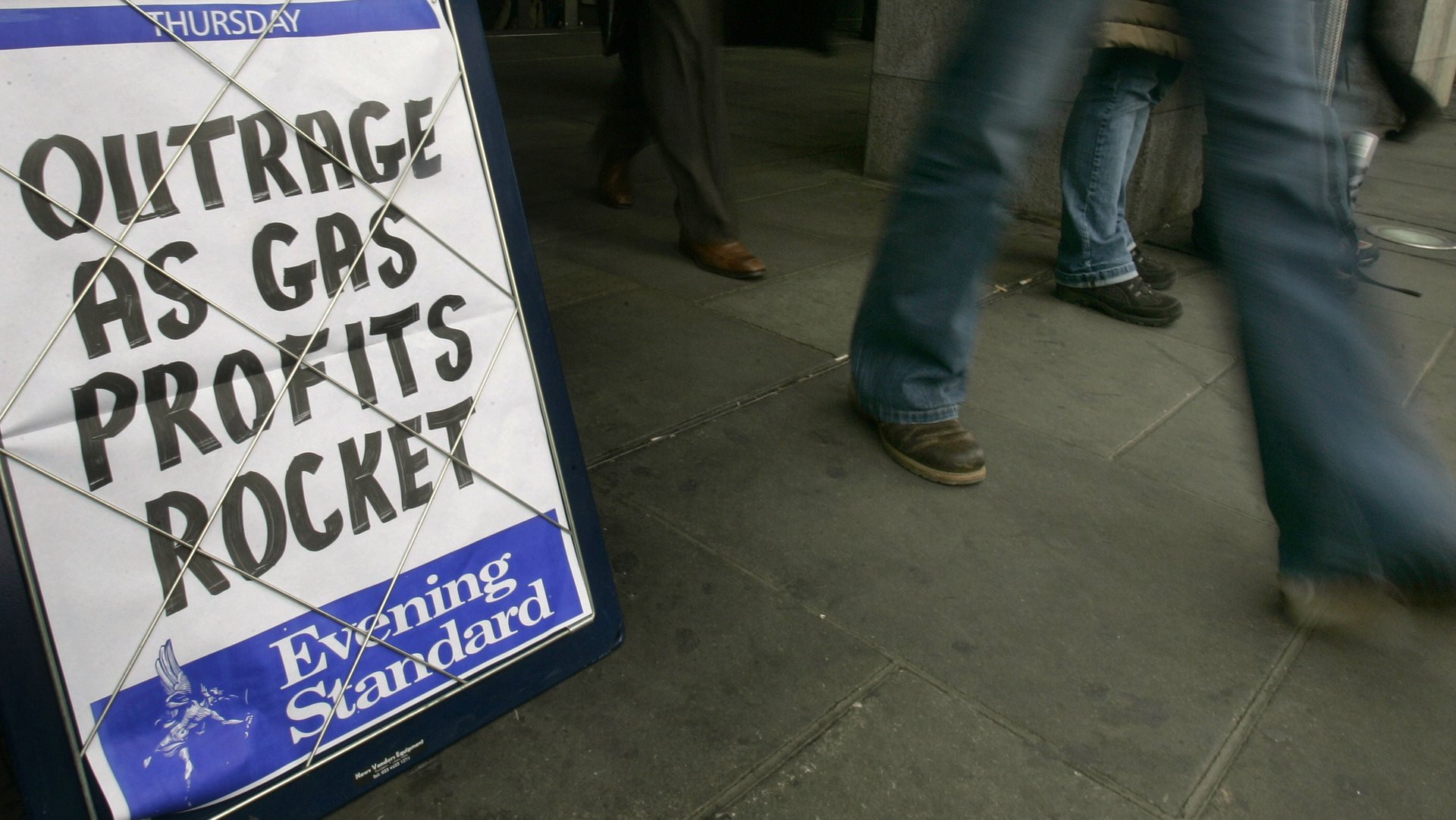

And so now the press is abuzz with claims that the £300 billion ($477 billion) wholesale gas market may have been rigged like LIBOR.

Like with LIBOR, prices are based on reported figures from the industry. As Freedman has told media, at 4:30pm each weekday, he would survey a sample of traders to learn where the “day-ahead” contract (an influential contract) was trading, at exactly that moment. Some traders report numbers over the phone, others send screen shots from their computers. Like LIBOR, it operates on an honor system. The numbers are used to help set a benchmark price, upon which wholesalers base their long-term supply contracts. On Sept. 28, Freedman says low bids outside the bid and offer range, set off alarm bells. Although the difference was a fraction of a penny, the wholesale price of gas can be affected by millions of pounds.

Similar to LIBOR, the reporting comes from the industry. The relationship is suspiciously cosy. Price reporting agencies (PRAs) like ICIS Heren are funded through subscriptions sold to energy companies, which trade in financial products based on prices set by traders and analysts working for energy companies.

Experts say energy prices are easier to rig than bank rates because the trades are mostly made between companies rather than through an electronic trading system, making trades more opaque. David Hunter, an analyst at M&C Energy Group said:

This sort of trading is less transparent than a fully fledged market. Hypothetically someone could seek to artificially lower the price by making small trades below the prevailing market price that may benefit them.

Freedman separately tipped off the Guardian newspaper, saying “some of the big six” energy providers were involved in fixing prices to either raise or lower wholesale gas prices. He said that traders told him that the practice was an “open secret” and that benchmarks (ICIS Heren is not the only publisher of figures upon which prices are set) were unreliable as “traders regularly put price reporters under pressure to change prices they disagree with.”

With energy prices set to rise again in Britain, Arlene McCarthy, a UK member of the European Parliament and a committee member for Internal Market and Consumer Protection, stirred up tensions by saying:

For some time I have feared there is an extensive cartel culture of market-rigging and price-fixing in the commodities markets. Companies guilty of abuse must face the full force of penalties and sanctions and jail for criminal behavior.

Four of the UK’s biggest six energy suppliers have denied involvement.