Growth is stagnant and deflation is looming. What is Mario Draghi waiting for?

The devil is in the details, Mario Draghi learned today.

The devil is in the details, Mario Draghi learned today.

At a press conference, the European Central Bank president said little about his efforts to stave off deflation by boosting the balance sheet—the base of the money supply—of the central bank. Many believe that the ECB needs to buy up at least €1 trillion ($1.26 trillion) in bonds and other securities to make a difference to the euro zone’s economy. No numbers were forthcoming.

Of course, Draghi said little beyond that he was willing to do “whatever it takes” to defend the euro zone from collapse back in 2012. That succinct statement alone took the heat off of countries on the brink of default, with a steady and sustained decline in borrowing costs since then eased the pressure on member of the euro zone’s beleaguered “periphery.” These countries are now slowly—very slowly—getting their fiscal houses in order.

But more than two years after that famous promise, the pace of actual action at the ECB remains glacial. Today, traders looked to Draghi for details of a major bond-buying program he previewed last month. (That was when the ECB said it would buy asset-backed securities and mortgage-backed bonds from banks across the euro zone in hopes of freeing up funds to lend to hard-up small businesses and other cash-strapped borrowers.)

The traders were largely disappointed. The main announcement today concerned a few details about ECB plans to buy junk bonds from Greece and Cyprus, but that’s about it. Draghi only said that the “potential universe” of things the ECB would consider buying was €1 trillion. There were no indications of a plan to buy from the bottomless well of government bonds, like in the US, UK, and Japan.

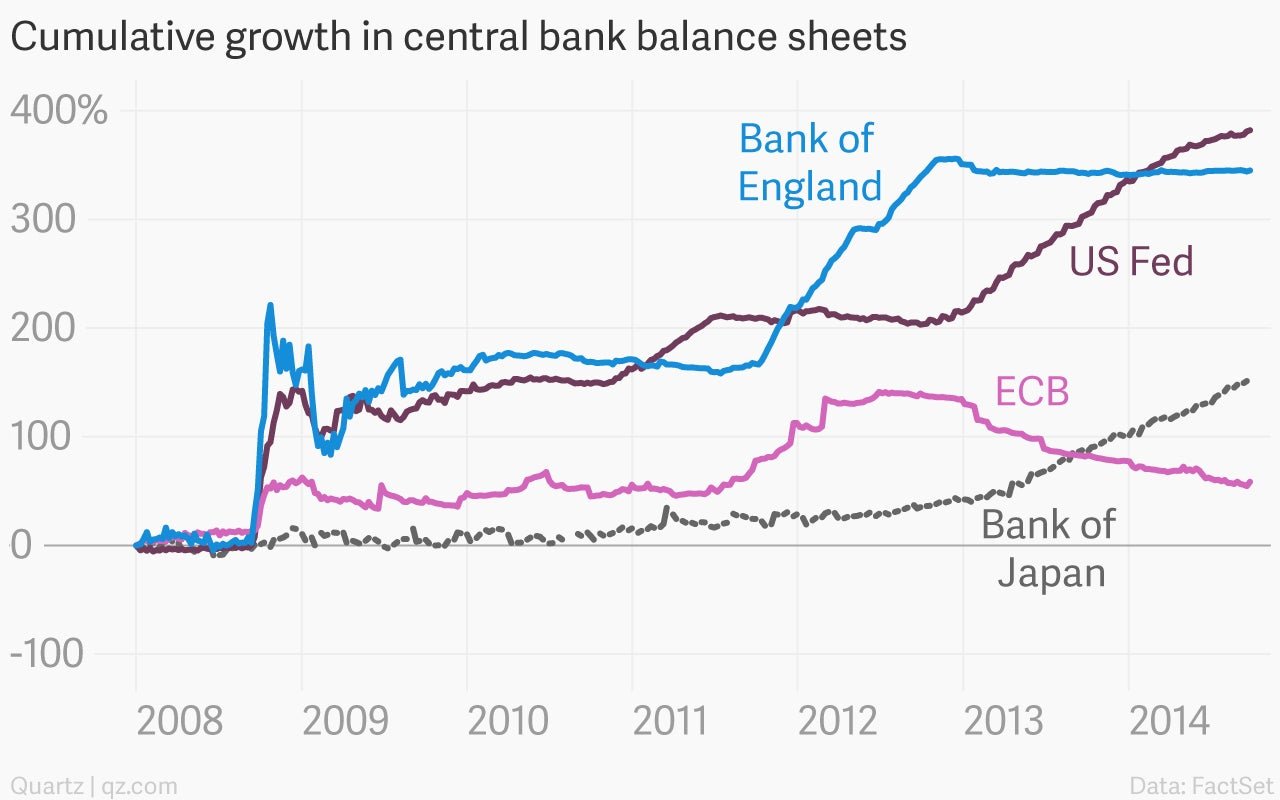

Many think such a plan is necessary if the ECB is to actually expand its balance sheet enough to offer material support to the economy. The ECB hasn’t been nearly as aggressive as other major central banks, even as the euro zone economy struggles mightily:

For this reason, analysts’ notes published after today’s meeting mostly played on the “Draghi disappoints” theme. The normally mild-mannered president showed some exasperation himself. “I understand your desire to have very precise figures for everything,” he told the press pack. “That makes life perhaps easier.” (For his part, Draghi’s life will get easier next year when the ECB plans on holding fewer press conferences.)

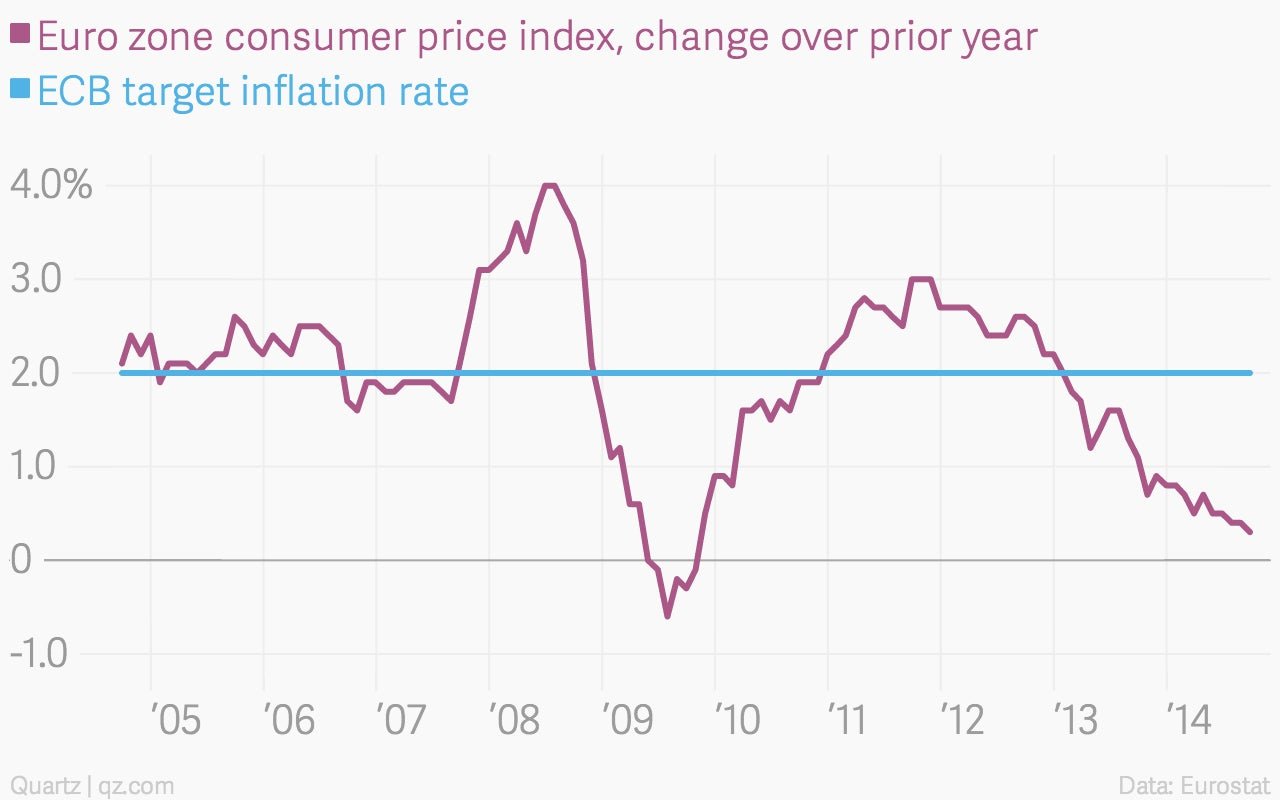

But if Draghi believes the press corps are the only ones eager for answers, he’s mistaken. The euro zone is dangerously close to slipping into a deflationary spiral, a malaise that has proven economically debilitating to Japan for decades.

In the short term, the central bank is the entity best able to counter that trend. But turning around huge economies takes time. Unlike after previous press conferences this year, the euro held firm on Draghi’s comments, which won’t help the ECB fight against low and falling inflation.

Azad Zangana of Schroders wrote in a note that the vagueness around the bond-buying plan, which will be rolled out in stages starting later this month, reflects an understanding at the ECB that it won’t be able to meet the market’s lofty expectations, or possibly that not all of its governors are comfortable with even a modest expansion of the bank’s balance sheet. Instead, the ECB is in “wait and see mode,” he says. But how much longer can it rely more on words than deeds?