HP strayed from its strengths long before its recent dysfunction

Finally! HP did what everyone but its CEO and board thought inevitable: It spun off the commoditized PC and printing businesses. This is an opportunity to look deeper into HP’s culture for roots of today’s probably unsolvable problems.

Finally! HP did what everyone but its CEO and board thought inevitable: It spun off the commoditized PC and printing businesses. This is an opportunity to look deeper into HP’s culture for roots of today’s probably unsolvable problems.

The visionary sheep of Corporate America are making a sharp 180º turn in remarkable lockstep. Conglomerates and diversification strategies are out. Focus, focus, focus is now the path to growth and earnings purity.

As reported in last week’s Monday Note, eBay’s John Donahoe no longer believes that eBay and PayPal “make sense together,” that splitting the companies “gives the kind of strategic focus and flexibility that we think will be necessary in the coming period.” This week, Symantec announced that it will spin off its storage division (née Veritas) so that “the businesses would be able to focus better on growth opportunities including M&A.”

And now Meg Whitman tells us that HP will be “a lot more nimble, a lot more focused” as two independent companies: HP Inc. for PCs and printers, Hewlett-Packard Enterprise for everything else.

Spinning off the PC and printer business made sense three years ago when Léo Apotheker lost his CEO job for suggesting it, and it still makes sense today. But this doesn’t mean that an independent HP PC company will stay forever independent. In a declining PC market that it once dominated, HP has fallen behind Lenovo, the company that acquired IBM’s PC business and made the iconic ThinkPad even more ubiquitous. HP Inc. will also face a newly-energized Dell, as well as determined Asian makers such as Acer and Asus. That Acer is losing money and Asus’ profits have fallen by 24% will make the PC market even more prone to price wars and consolidation. It doesn’t take much imagination to foresee HP Inc. shareholders agitating for a sale.

Many think that Hewlett-Packard Enterprise’s future isn’t so bright, either. The company’s latest numbers show that the enterprise business—which competes with the likes of IBM, Oracle, and SAP—isn’t growing. As with the PC business, such an unexciting state of affairs leads to talk of consolidation, of the proverbial “merger of equals.”

Such unhappy prospects for what once was a pillar of Silicon Valley lead to bitter criticism of a succession of executives and of an almost-surreal procession of bad board decisions. Three years ago, I partook in such criticism in a Monday Note titled “How Bad Boards Kill Companies: HP.” This was after an even-older column, “The Incumbent’s Curse: HP,” where I wistfully contemplated the company’s rise and fall.

I’m fascinated by the enduring power, both negative or positive, of corporate cultures, of the under-the-surface system of emotions and permissions. After thinking about it, I feel HP’s current problems are rooted more deeply and started far earlier than the board’s decisions and the sorry parade of executives over the past 15 years.

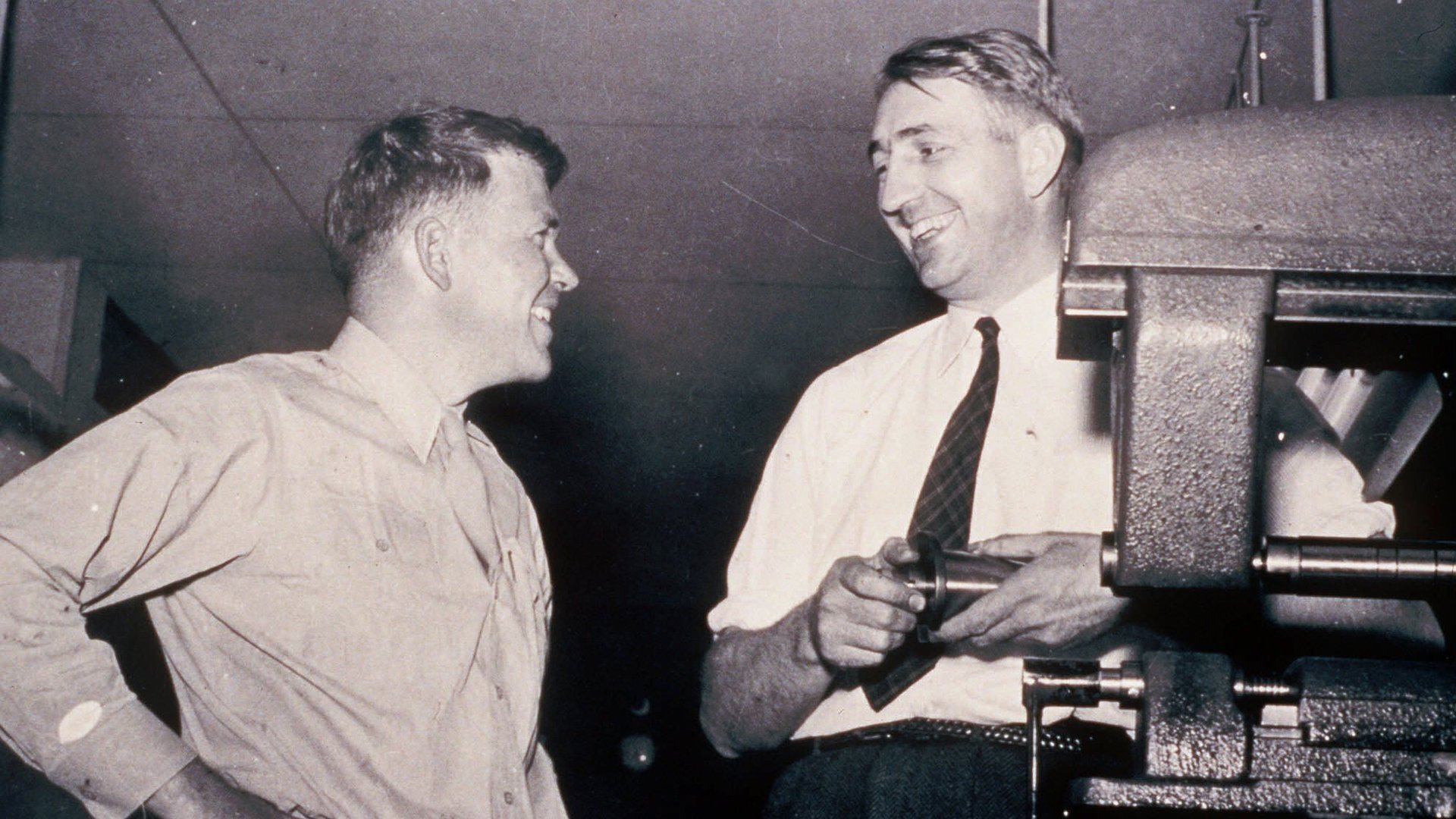

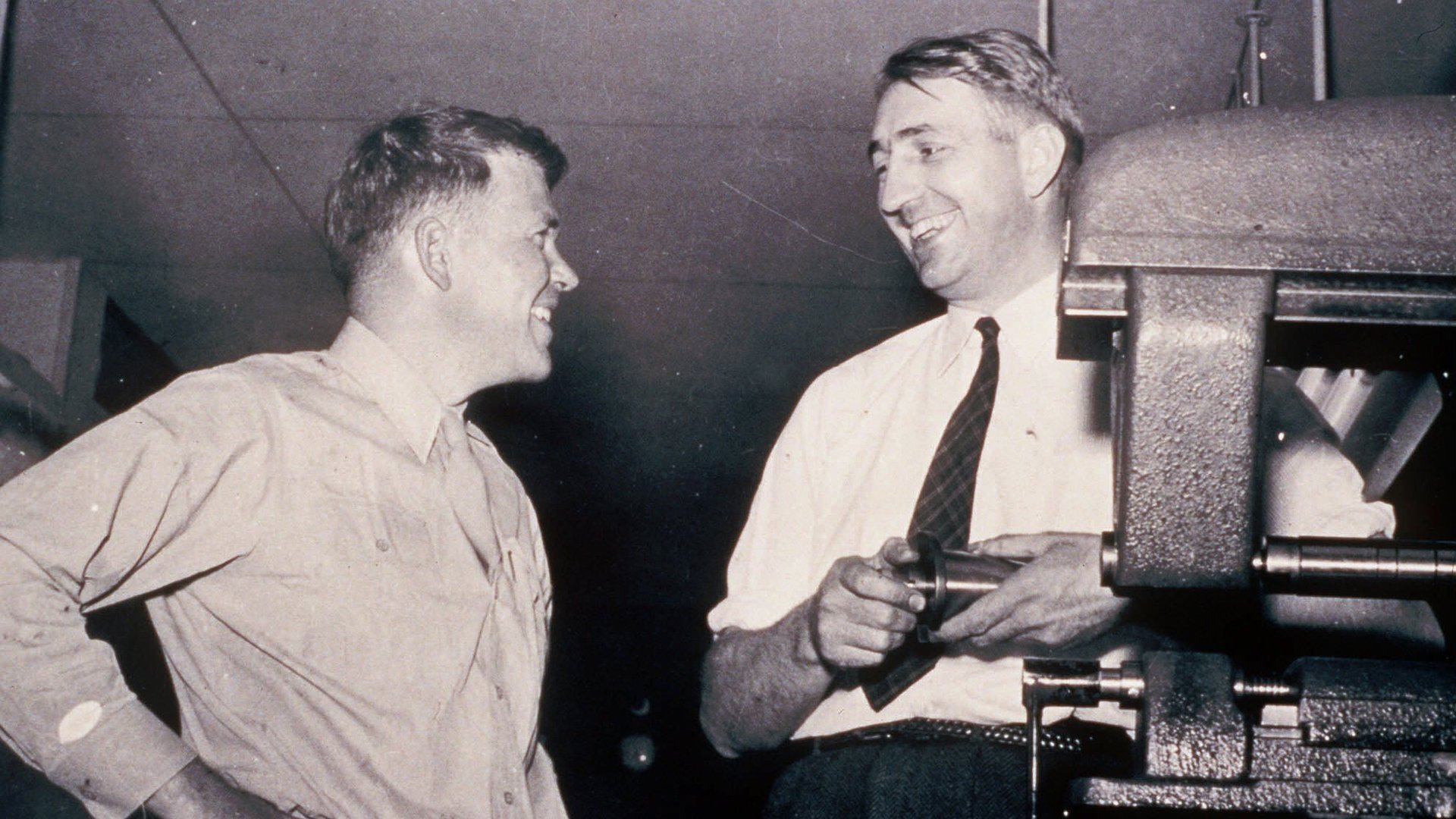

Founded in 1939, HP spent a quarter century following one instinct: Make products for the guy at the next bench. HP engineers could identify with their customers because their customer were people just like them…it was nerd heaven.

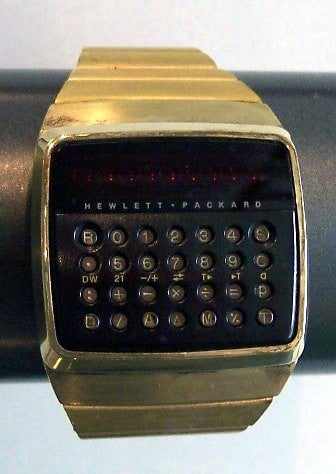

HP’s line of pocket calculators is the exemplar of a company following its instincts. They worked well because they appealed to techies. The amazingly successful HP-80 was a staple of the financial world; its successor, the HP 12-C, is still sold today.

But HP’s initial success bred a strain of “Because We Can” that led the company into markets for which its culture had no natural feeling. I’m not just referring to the bizarre attempt in 1977 to sell the HP-01 “smartwatch” through jewelry stores…

No, I’m referring to computers. Not the technical/scientific desktop kind, but computers that were marketed to corporate IT departments. In the late ’60s, HP embarked on the overly ambitious Omega project, a 32-bit, real-time computer that was cancelled in 1970. The “Because We Can” impulse of HP engineers wasn’t supported by a reliable internal representation of the customer’s ways, wants, and emotions. (A related but much more modest project, the 16-bit Alpha, ultimately led to the successful HP 3000—but even the HP 3000 had a difficult birth.)

Similarly, when 8-bit microprocessors emerged in 1974, HP engineers had no insights into the desires of the unwashed hobbyist. They couldn’t understand why anyone would embrace designs that were clearly inferior to their pristine 16-bit 9800 series of desktop machines.

By the late ’70s the company was bisected into engineers who stuck to the “guy at the next bench” approach, and engineers who targeted the IT workers that they mistakenly thought they understood. Later, in 1999, the instrument engineers and products—the “real” HP to many of us—were split off into Agilent, a relatively small business that’s not very profitable. The company’s less than $7 billion in revenue is nothing compared to the more than $100 billion in yearly revenues for the pre-split HP.

In all industries, some companies manage to stick to their story, while others drift from the script. I’m thinking of Volkswagen and its 40-year old Golf (not the misbegotten Phaeton) versus Honda’s sprightly 1972 Civic hatchback that later lost its soul and turned into today’s banal little sedan. (To be fair, I see the Civic as alive and well in the Honda Fit.)

In the tech world, Oracle has kept to the plot—no doubt because the founder, Larry Ellison, is still at the helm after 37 years. Others, like Cisco, make bizarre acquisitions: Flip, a consumer camera company that it quickly shut down, and home networking company LinkSys (purchased at a time when CEO John Chambers called the home his company’s next frontier.) And now Cisco is going after the $19 trillion (trillion!) Internet of Things.

The now dysfunctional Wintel lost the plot by letting the PC-centric intuitions that worked well for so long blind them to the fact mobile devices aren’t “PCs— only smaller.”

I have a personal feeling of melancholy when I see that the once-mighty HP has drifted from its instincts. The company hired me in June 1968 to launch its first desktop computer on the French market. After years in the weeds, this was the chance of a lifetime for this geeky college drop-out. At the time I joined, HP’s vision was concentrated. It rarely acquired other companies…why buy what you can build yourself? That all changed, and in a big way, in the ’90s.

To this day, I’m grateful for the kindness and patience of the HP that took me in. It was the company that David Packard describes in The HP Way, not today’s tired conglomeration.

You can read more of Monday Note’s coverage of technology and media here.