We’re about to find out what the future of HBO will look like

Update October 15: HBO announced it will begin selling standalone subscriptions over the internet, without cable, starting next year.

Update October 15: HBO announced it will begin selling standalone subscriptions over the internet, without cable, starting next year.

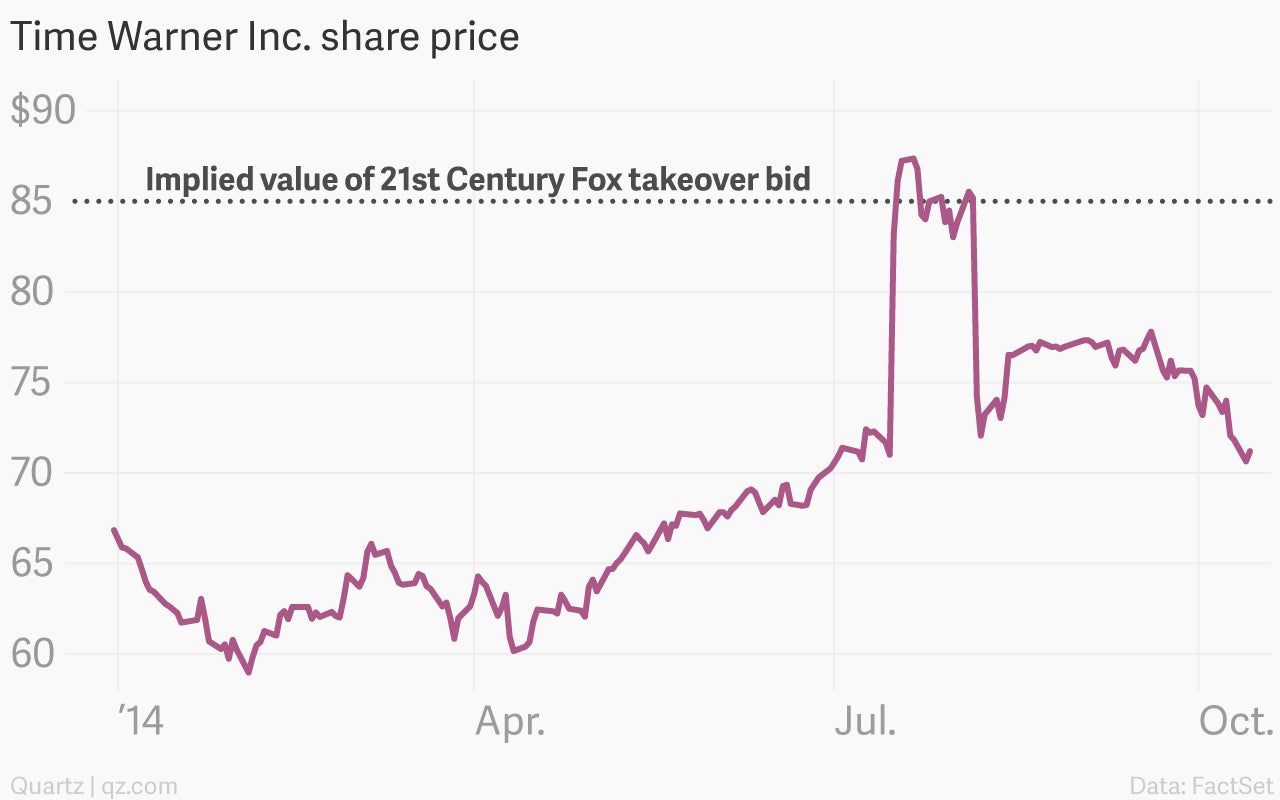

Tomorrow marks exactly three months since news surfaced that Rupert Murdoch’s 21st Century Fox had bid $80 billion for Time Warner, the owner of HBO, CNN, and various other film and TV assets. Fittingly, tomorrow also is when Jeff Bewkes, Time Warner’s CEO, will face investors and explain why he rejected the approach.

Bewkes officially knocked back the offer, worth $85 per share at the time, because he believes his own strategy will create more sustainable value for shareholders. Yet, job cuts aside, we still don’t really know what his plan involves. On the eve of an investor meeting that will be webcast on the company’s website, Time Warner’s stock price has now fallen back to the levels where it was trading before news of the Murdoch approach first emerged.

But Bewkes does have one ace up his sleeve, in the form of HBO.

Many feel the premium channel, with its seemingly endless stream of insanely popular shows, still has plenty of room for growth. At the moment, it’s straightjacketed by the fact that is still only accessible (legally) with some form of pay TV subscription. But last month, Bewkes said he was “seriously considering” the idea of offering HBO’s streaming product, HBO Go, à la carte, effectively splitting the online service from cable TV subscriptions.

Todd Juenger, an analyst at Bernstein Research, reasoned in a research note last month that unchaining HBO Go in the US could lead to huge growth in the number of paying customers. ”The most obvious opportunity Time Warner has to argue for earnings upside is at HBO,” he wrote.

But the strategy also would involve substantial costs. For example, HBO Go (which has suffered notable outages during high-profile episodes of hit shows) would have to invest heavily in its streaming infrastructure and secure favorable agreements with internet service providers to pump out its content smoothly to users. (The latter is something Netflix has struggled with).

Alternatively, Time Warner could work with more pay TV companies to promote slimmed-down packages that still include broadband access and HBO. Such packages, aimed at blunting the “cord-cutting” trend, already are being offered by Comcast and AT&T. This strategy would eliminate many of the costs associated with a full-fledged, direct-to-consumer offering, but could hurt viewership for Time Warner’s other cable channels.

Another option—the one with “the most certain upside and least risk,” Juenger argued—would be for HBO to use the threat of going direct to consumers to glean more fees out of cable (and satellite or telecom) TV providers, who at the moment have exclusive rights to sell the channel. Pay TV operators “make a lot of money from selling HBO. They are better off paying a bigger share to HBO than losing their cut altogether,” he wrote.

That might be an uninspiring option from a consumer perspective; whether investors could get excited about it is another matter completely. If Bewkes and Time Warner disappoint with their plans for HBO, pressure from shareholders over their rejection of Fox may begin to mount. And that could provide Fox with an opening to return with another bid, even if Murdoch has downplayed the possibility of further pursuit.