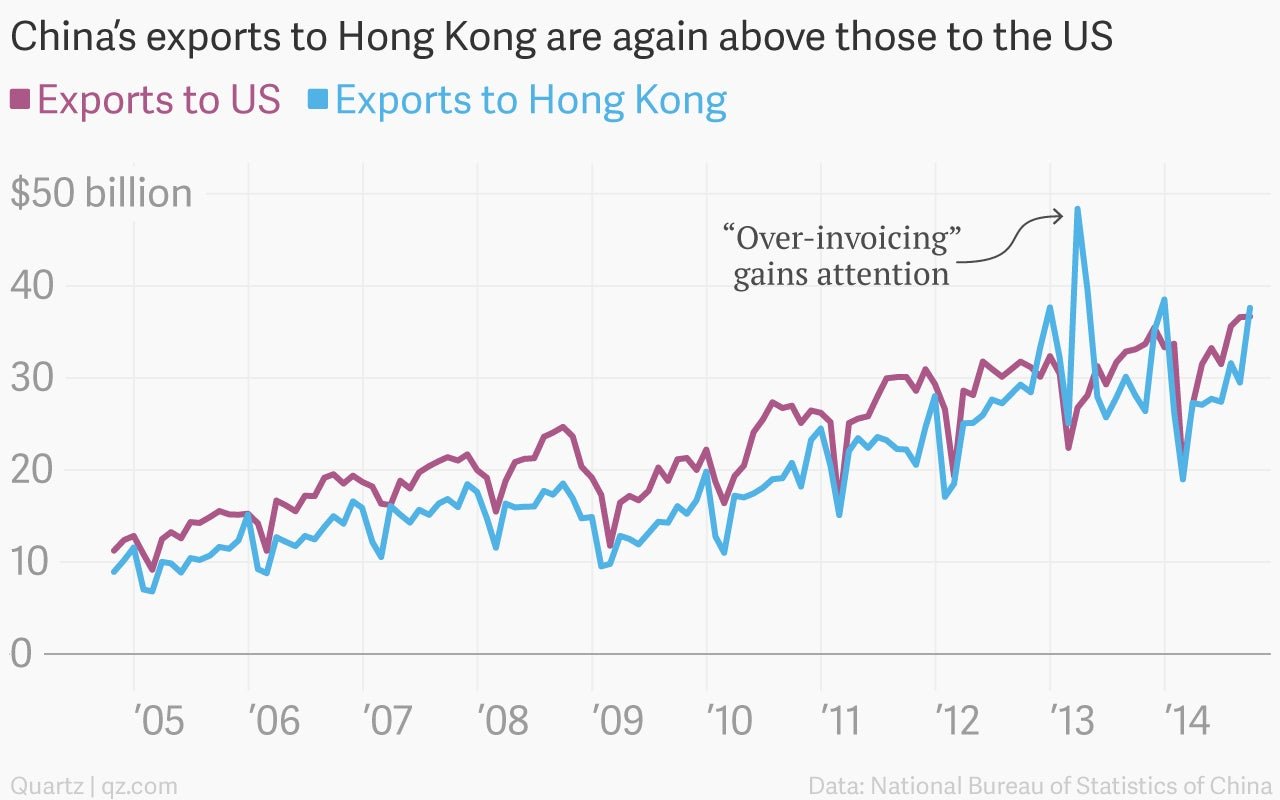

Uh-oh, those shady “exports” from China to Hong Kong are back

Last Spring, Chinese exports to Hong Kong mysteriously exploded. Actually, it wasn’t that mysterious. Many observers put the surge of exports to Hong Kong from the mainland down to a phenomenon known as “over-invoicing.” Essentially, money was flowing into China as payment for fictitious goods. Why? Because it was one of the few ways for investors to sneak their capital into the tightly controlled Chinese market, where a relatively fast-growing economy is like catnip to global investors.

Last Spring, Chinese exports to Hong Kong mysteriously exploded. Actually, it wasn’t that mysterious. Many observers put the surge of exports to Hong Kong from the mainland down to a phenomenon known as “over-invoicing.” Essentially, money was flowing into China as payment for fictitious goods. Why? Because it was one of the few ways for investors to sneak their capital into the tightly controlled Chinese market, where a relatively fast-growing economy is like catnip to global investors.

The ridiculousness of the data in the Spring of 2013 prompted the Chinese government to crack down on the practice. For much of the last year, the traditional pattern reasserted itself.

But in September, Chinese exports to Hong Kong again rocketed higher, rising 34% compared to the same month last year. So what’s going on? Analyst have suggested a number of explanations, including the fact that regional Chinese policy makers are attempting to meet end-of-year growth goals, though little actual evidence of such a phenomenon exists.

But if “over-invoicing” really does reflect shadow capital flows into China, one has to consider that the Chinese economy is looking increasingly weak. And the government is taking a number of steps to ease financial conditions, from easing short-term lending rates to injecting billions in cash into large Chinese banks in the form of short-term loans. Against such a backdrop, it’s worth considering whether Chinese policy makers might be more willing to allow foreign inflows of capital—in the form of fictitious exports—in an effort to shore up growth.