What everyone is missing about today’s wild ride in the markets

Financial markets snapped back and forth today. (Stocks, bonds, commodities, currencies all got pretty lively.) But how much new information did the kerfuffle provide to investors about the prospects for prices, profits, and economic growth? Incredibly little, actually.

Financial markets snapped back and forth today. (Stocks, bonds, commodities, currencies all got pretty lively.) But how much new information did the kerfuffle provide to investors about the prospects for prices, profits, and economic growth? Incredibly little, actually.

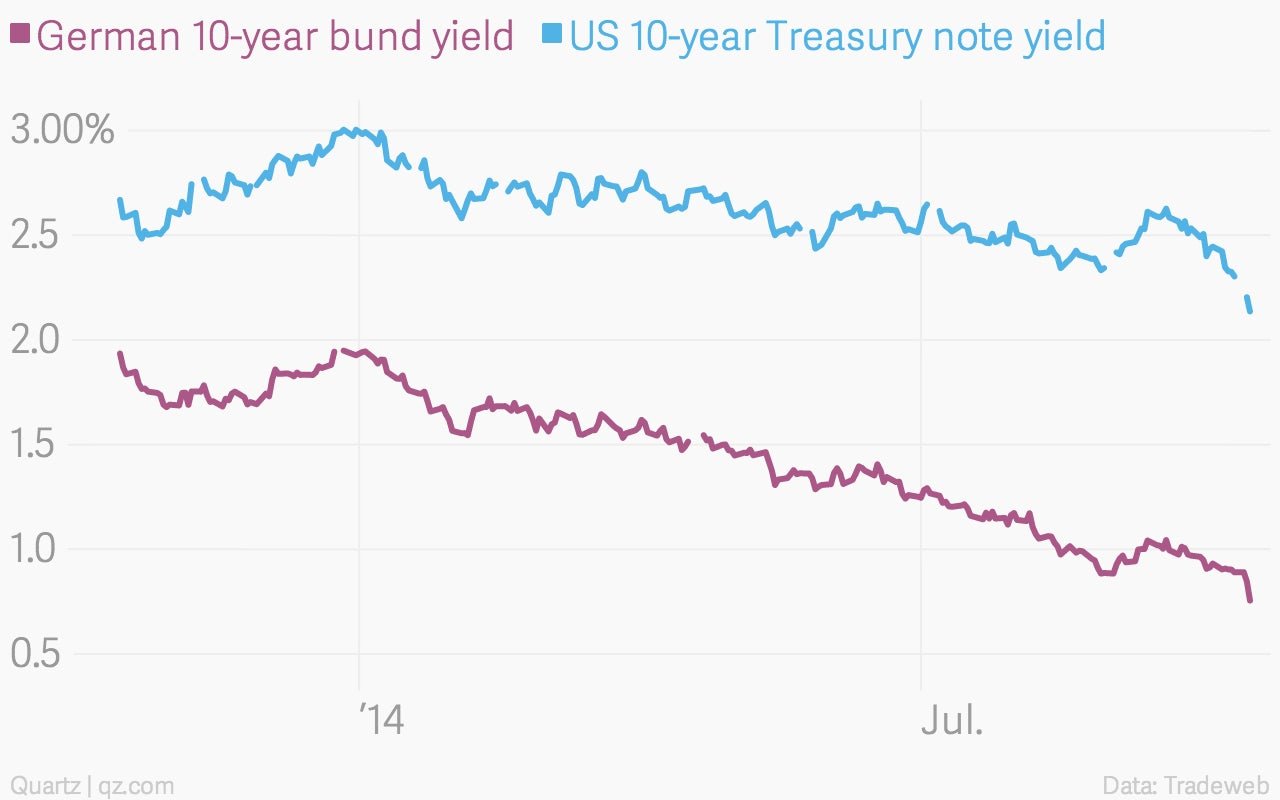

For weeks now, the markets have been showing signs of growing concern that a persistent slowdown in price growth could turn into outright deflation, a dangerous economic situation that can persistently undermine economic growth. Bond yields have been falling in Asia, Europe, and the US, as investors have shown a growing risk aversion. (Risk averse investors buy government bonds, pushing up prices, and pushing down yields.) The the decline today was quite sharp, but the trend has been in place for a while now.

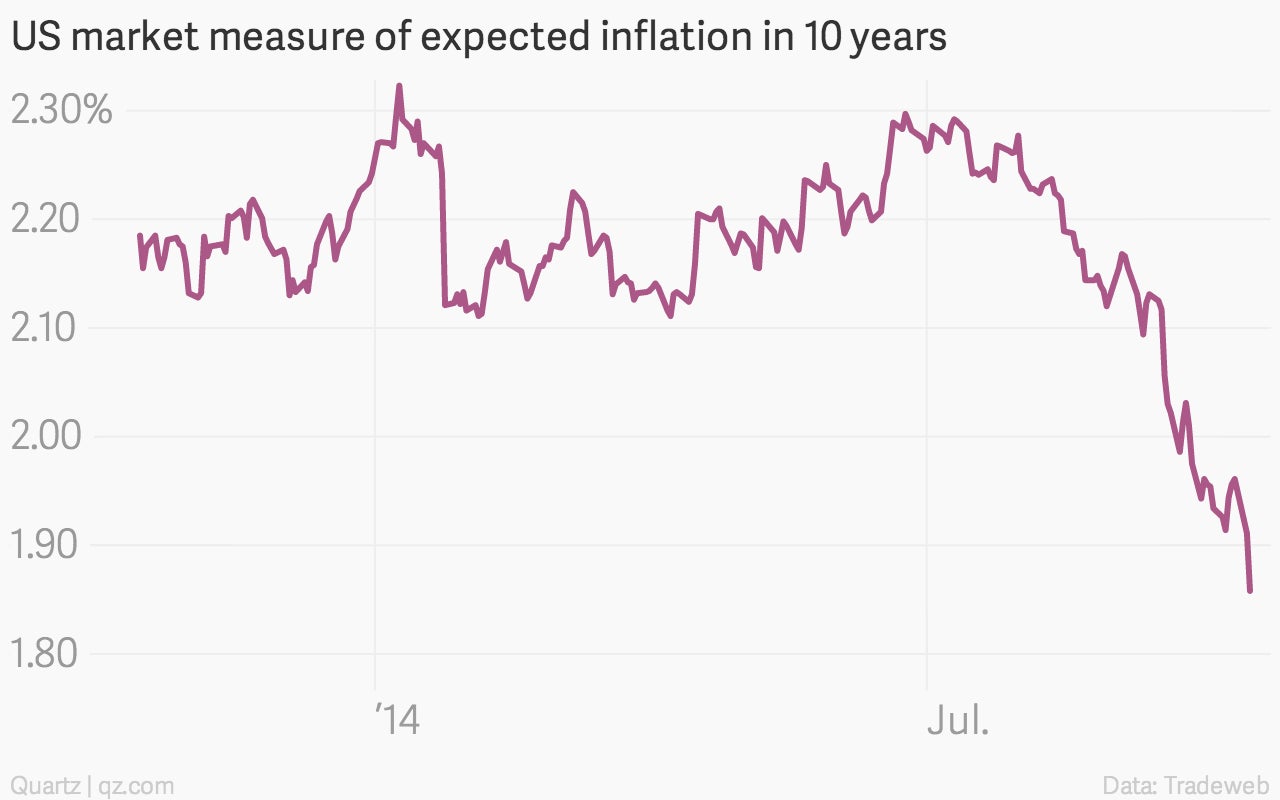

Market measures of inflation expectations, such as ten-year break-evens, have also been moving lower, suggesting investors don’t see inflation as remotely likely. Break-evens, too, fell sharply today. But, again, we already knew there was little risk of inflation and rising risks of deflation.

So was there any new economic data or information that arrived that informed investor decisions? Nope, not really. We’re in the slim pickings segment of the monthly economic data calendar. Sure, US retail sales fell and producer prices were a bit worse than expected. What about outside the US? Still, no big numbers. Weak Chinese inflation? Strong Brazilian retail sales? These aren’t major, market-moving reports. And they surely don’t explain this.

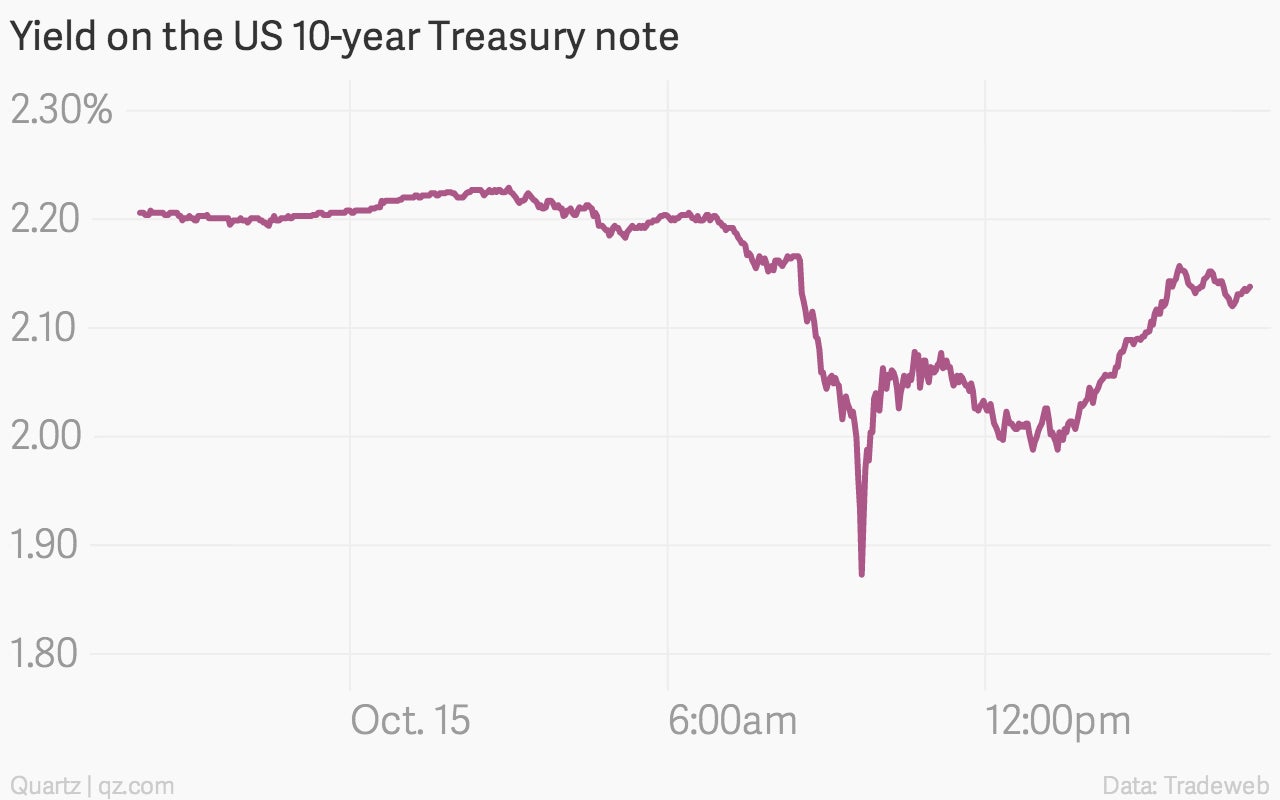

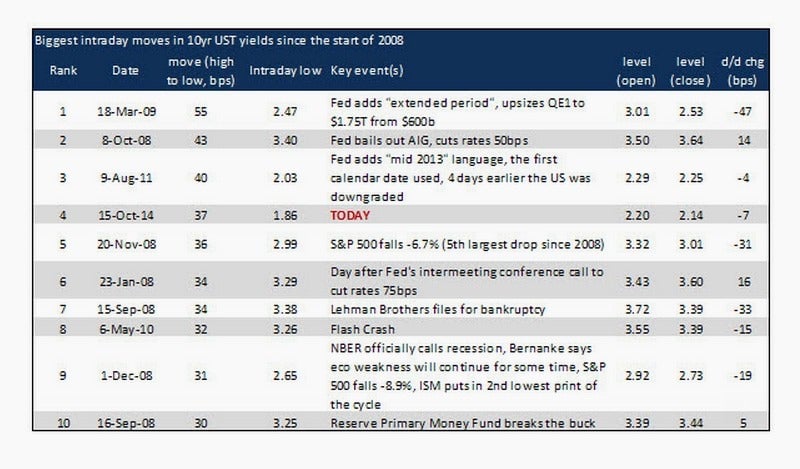

At around 9:40am New York time, prices for US government bonds surged sharply, pushing yields down. If you don’t follow the bond market, it might not look like much, but the yield on the US Treasury note fell by 0.37 percentage points from peak to trough today. That is an absolutely massive move, the kind of thing that, in recent years, we’ve only seen in moments of outright market panic. This terrific chart from market analysts at RBC Capital shows where today’s Treasury action ranks.

Interest rates, we’re told, are set by the markets based on big, slow-moving macroeconomic factors such as the outlook for economic growth, demographics and expectations about inflation and monetary policy. Clearly the prospect for US economic growth and inflation didn’t deteriorate precisely at 9:40am (and then quickly improve).

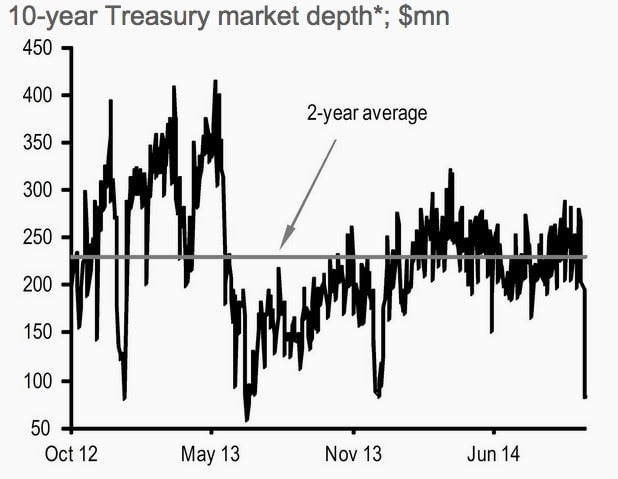

So what happened? Well, what seemed to be happening was actually pretty remarkable. The giant ocean of liquidity that is the market for US Treasury securities—the world’s deepest and most liquid market—suddenly looked a lot like the shallow end of the pool. J.P. Morgan analysts grabbed the snapshot at right. It’s a gauge of market depth, which they define as the average average size of the top three bids and offers—basically the size of the standing orders to buy and sell—in the Treasury market.

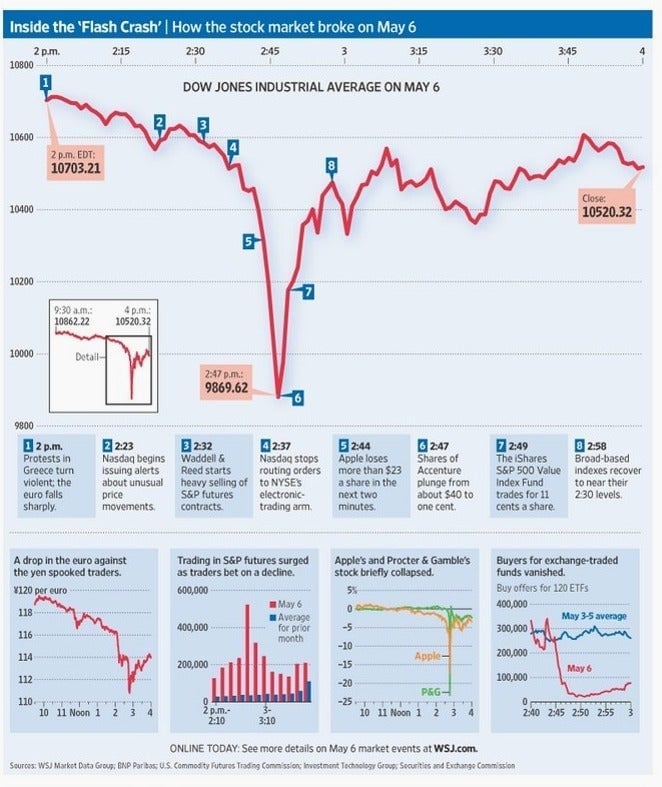

Analysts at Credit Suisse called the sudden dry-up a “liquidity event.” But it’s something akin to what the equity markets experience during the so-called “flash crash” on May 6, 2010. Actually the chart of that Flash Crash looks sort of similar to today’s Treasury market situation. Here’s the Wall Street Journal’s graphic depiction of how that went down back in 2010:

Now, these kind of things happen from time to time. But they’re not supposed to happen in the market for US Treasurys, which appeal to investors precisely because of the unparalleled depth and liquidity. Depth and liquidity—and of course safety—are effectively the brand of US Treasury market. And anything that damages that reputation is really important, as it forces the world’s reserve managers—like, you know, China—to rethink whether they want to park their giant surpluses in US Treasurys and the US dollar.

That has implications for the manner in which the United States finances its persistent current account deficits, the health of the dollar, the functioning of US monetary policy, and financial conditions for millions of Americans. (Not to mention millions around the world, where US Treasurys also serve as an important benchmark of risk.) I have no idea why Treasurys suffered a mini-flash crash today. But somebody—Congress—really needs to get to the bottom of it.