Burying bad news: China banks’ bad debts keep rising, regulator says on day country gets new leaders

All eyes were on China on Thursday as the country unveiled its new Politburo Standing Committee. Beijing’s entire foreign press corps and quite a few parachuted-in journalists were hanging around the Chinese capital’s Great Hall of the People to get a glimpse of the new leaders, then spent the day filing their analyses of what the new lineup meant. What a good day, then, for China’s banking regulator to release bad news about the declining health of China’s state-owned lenders. Coverage was, unsurprisingly, very scant.

All eyes were on China on Thursday as the country unveiled its new Politburo Standing Committee. Beijing’s entire foreign press corps and quite a few parachuted-in journalists were hanging around the Chinese capital’s Great Hall of the People to get a glimpse of the new leaders, then spent the day filing their analyses of what the new lineup meant. What a good day, then, for China’s banking regulator to release bad news about the declining health of China’s state-owned lenders. Coverage was, unsurprisingly, very scant.

Bad debts at Chinese banks rose by $4 billion in the third quarter of this year, the Chinese Banking Regulatory Commission said Thursday. This was the fourth consecutive quarter the figure has grown, and the longest period of quarterly increases in bad loans since 2004. The cause of the rising bad debts is the massive economic stimulus the Beijing government unleashed in 2009-2010, which involved banks lavishing record amounts of credit on borrowers such as local governments and property developers, which in turn built unviable projects, such as ghost towns and empty shopping malls.

It is the ongoing trend of rising bad loans that should be of interest here. Economists do not pay much attention to CBRC’s calculation of the amount of bad loans in the Chinese system—which the regulator puts at just 0.95% of total assets—because Chinese lenders are notorious for under reporting bad debts and flattering their balance sheets by restructuring and evergreening loans.

Chinese lenders are generous with themselves about how they classify other bad debts. The 0.95% figure the CBRC reports only accounts for the worst, most toxic hopeless loans on the banks’ books. They follow international accounting standards and classify their loans as either ”pass,” “special-mention,” “substandard,” “doubtful” or “loss.” But their classification is not conservative. As the influential and independent Chinese financial magazine Caixin notes here, the CBRC gives Chinese lenders “considerable leeway in determining whether a loan is toxic or not. Classifying a loan as one notch above NPL status, referred to as ‘special mention,’ allows banks to suppress the level of bad loans and avoid drawing extra reserves for potential loss.”

Economists differ on what the real bad debt figure might be in the Chinese banking system. Charlene Chu of credit ratings agency Fitch, who has probably scrutinized the Chinese banks’ balance sheets more than any other analyst, noted in a mid-October presentation to clients that non-performing loans and special mention loans in the system added up to around 3-6% of gross loans. That does not sound too bad for an emerging market.

But Chinese banks may not have the cash to bail themselves out. The real problem, Chu said in her presentation, is that Chinese lenders are thinly capitalized. She forecast that if bad and special mention loans rise to 10% of gross loans and stay there for the next two years, this would “burn through the [banking] sector’s entire pre-provision profit for both years, as well as half its equity.”

Some Chinese lenders have raised their bad loan provisions since Chu issued this forecast. The nations’ biggest banks are increasing provisions by a massive 20-48 percentage points, it emerged in late October.

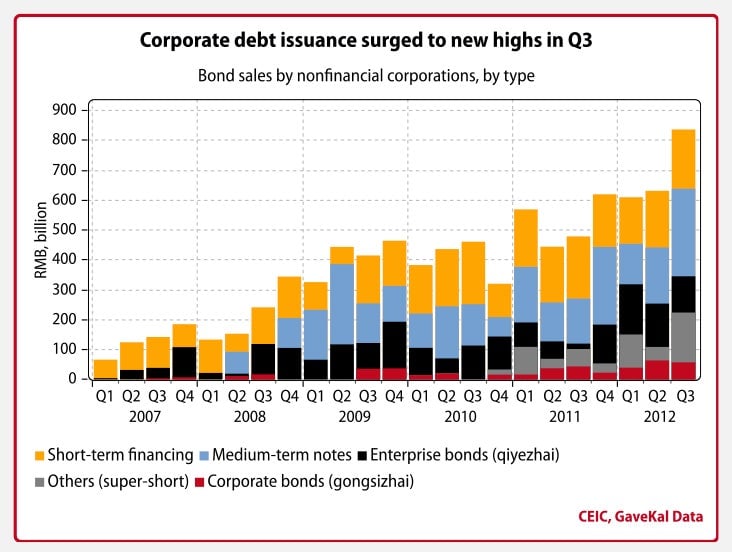

But the provisions are only growing alongside the increasing risk of new bad debts. The banks are still working through the toxic loans they made in 2009-2010. And now the central government has started another round of stimulus spending and credit is exploding again. For example, the Ministry of Railways is going to spend $32 billion by the end of this year, even though passenger demand for its new high-speed train service is weak because of a deadly accident last year that was caused by design flaws. Ministry of Rail and other infrastructure projects are increasingly being funded by bonds instead of bank debt, as the below chart shows. But as China watcher and financial author Fraser Howie says here (paywall), the state-owned banks are the main buyers of corporate bonds anyway.

Here is an illustration of China’s most recent credit explosion, this time in the bond market and courtesy of economics consultancy Gavekal:

Does any of this matter? Analysts, for over two years, have been predicting Beijing will need to recapitalize its banks at some stage. That could dilute existing shareholders. So stock prices in the sector, such as that of China’s largest lender ICBC, have not been doing well. There is also the possibility that the weakness of Chinese banks could hobble the economy. As bad debts rise, it may become harder for Chinese banks to lend cash or buy bonds, which could choke growth. A pervasive argument is that Beijing can always tap the country’s $3 trillion-plus of dollar reserves. However some argue that may not be possible.

China may have a huge inflation problem if it tries to use its vast piles of forex reserves to save the banks, Carl Walter and Fraser Howie explain in the Wall Street Journal (paywall). Because China’s currency is non convertible, the central bank cannot simply reach into an offshore dollar account, pluck out some forex reserves and hand these to ailing banks to recapitalize them. This final thread of the bank bailout argument is difficult to follow. The short argument is that a bank bailout from forex reserves could cause monster inflation. Here is the long – and difficult – version of that argument:

The issue is that China’s capital account is closed and the yuan is non convertible.Walter and Howie write that while the People’s Bank of China can give banks dollars, that is not much help. The yuan is not freely convertible. So all the lenders can do with the dollars is stick them in an offshore account. What the banks will need is Renminbi (also called yuan). The holes in their balance sheets will have been caused by a shortfall in the domestic currency because borrowers are not repaying their yuan loans.

But because China’s currency is not freely convertible, each time the central bank buys dollars from exporters to add its forex reserves, it has to issue yuan to give back to the exporters. So if Beijing’ wanted to give its forex reserves to the banks in dollars, it could. The lenders, however, would then have to return to the central bank and sell these for yuan. And the central bank would have to buy the dollars from the banks again. And print more yuan to pay for it. As Walter and Howie outline in their WSJ article:

“No matter how such a transaction is structured—as a straight loan, as an option or as a currency swap—it is inherently inflationary in an economy with a non-convertible currency.”

China’s economic planners can mitigate this outcome, however, by forcing the banks to swap their forex bailout dollars for yuan slowly over a prolonged period so as not to cause a sudden inflation shock. But still, while huge forex reserves can protect countries against external debt crises, it is not certain they are much use in a domestic bank crises. As Michael Pettis of Peking University reminds us here, Japan built up huge dollar reserves in the 1980s, and then had a financial crisis in the 1990s from which it is still recovering.