Why Intel’s next CEO should come from Israel

With the impending retirement of Intel’s current CEO, Paul Otellini, the logical question is: who is next? Where can a company that could be ruined by its failure to get ahead of mobile find someone who is prepared to bust up its relatively conservative, navel-gazing internal culture?

With the impending retirement of Intel’s current CEO, Paul Otellini, the logical question is: who is next? Where can a company that could be ruined by its failure to get ahead of mobile find someone who is prepared to bust up its relatively conservative, navel-gazing internal culture?

There are plenty of company men and women in the upper echelons who could be the next CEO, but that was, in a way, Otellini’s problem—he’d been at Intel for 40 years. To find someone capable of reversing Intel’s declining fortunes, the company ought to look further afield—to Intel Israel, which is one of the country’s largest private-sector employers.

In the early 2000’s Otellini did do one thing right—he made a “right turn” in Intel’s processor strategy that set the company on a path to producing processors that did more with less power, rather than continuing an older trend of pumping so much electricity into Intel’s processors that they required elaborate cooling systems and were unsuitable for laptops.

It’s a move that saved the company. But, as outlined in the book Start-Up Nation, by Dan Senor and Saul Singer, Otellini and the old guard at Intel’s Santa Clara headquarters had to be bullied into making this change by the engineers at Intel Israel.

[Intel’s team in Israel] saw that Intel was headed for the “power wall.” Instead of waiting to ram into it, the Israelis wanted Otellini to avert it by taking a step back, discarding conventional thinking, and considering a fundamental change in the company’s technological approach.

That “fundamental change” was the move away from the “megahertz wars.” Chip companies, and the equity analysts who wrote reports on them, were obsessed with the “clock speed”, the number of operations a chip could carry out per second, measured in megahertz (and today in gigahertz). Intel Israel had been working on a more subtle design philosophy that emphasized making a chip handle instructions more efficiently, so it could process more of them for each watt of power. But one engineer quoted in Start-Up Nation described them as innovations that “no-one wanted.”

Yet those same designs now account for almost half of Intel’s revenue. What changed during the reign of Otellini is that every one of Intel’s customers suddenly got serious about the need to do more with less electricity.

Power became one of the the dominant costs in the data centers that are the computing infrastructure of Apple, Google, Microsoft, Yahoo, Amazon and every other company with a serious investment in the cloud. Meanwhile, as desktop PCs turned into laptops and people did more and more of their computing on mobile phones and tablets, batteries simply could not keep up. That’s the “power wall” that Intel would have smacked into had Intel’s Israeli engineers not made so many (20 hour) trips to Santa Clara that they were nearly ubiquitous. From Start-Up Nation:

The executives in Santa Clara were ready to strangle the Israeli team, according to some of those on the receiving end of Intel Israel’s “pestering.” … One point the Israelis tried to make was that while there was risk in abandoning the clock-speed doctrine, there was even greater risk in sticking with it. Dov Frohman, the founder of Intel Israel, later said that to create a true culture of innovation, “fear of loss often proves more powerful than the hope of gain.”

That “fear of loss,” the sense of anxiety about looming catastrophe that is, perhaps, uniquely Israeli, is precisely why Intel’s Israel division was so far ahead of the company’s US headquarters in perceiving a threat to Intel’s core business. Just as important, according to Senor and Singer, was Intel Israel’s culture of spirited debate, which included meetings in which engineers and management would scream at each other until they were red in the face.

Intel is a company in need of a mass slaughter of its sacred cows. Who better to accomplish that than someone from the team that has been pushing it toward power-sipping chips for mobile devices?

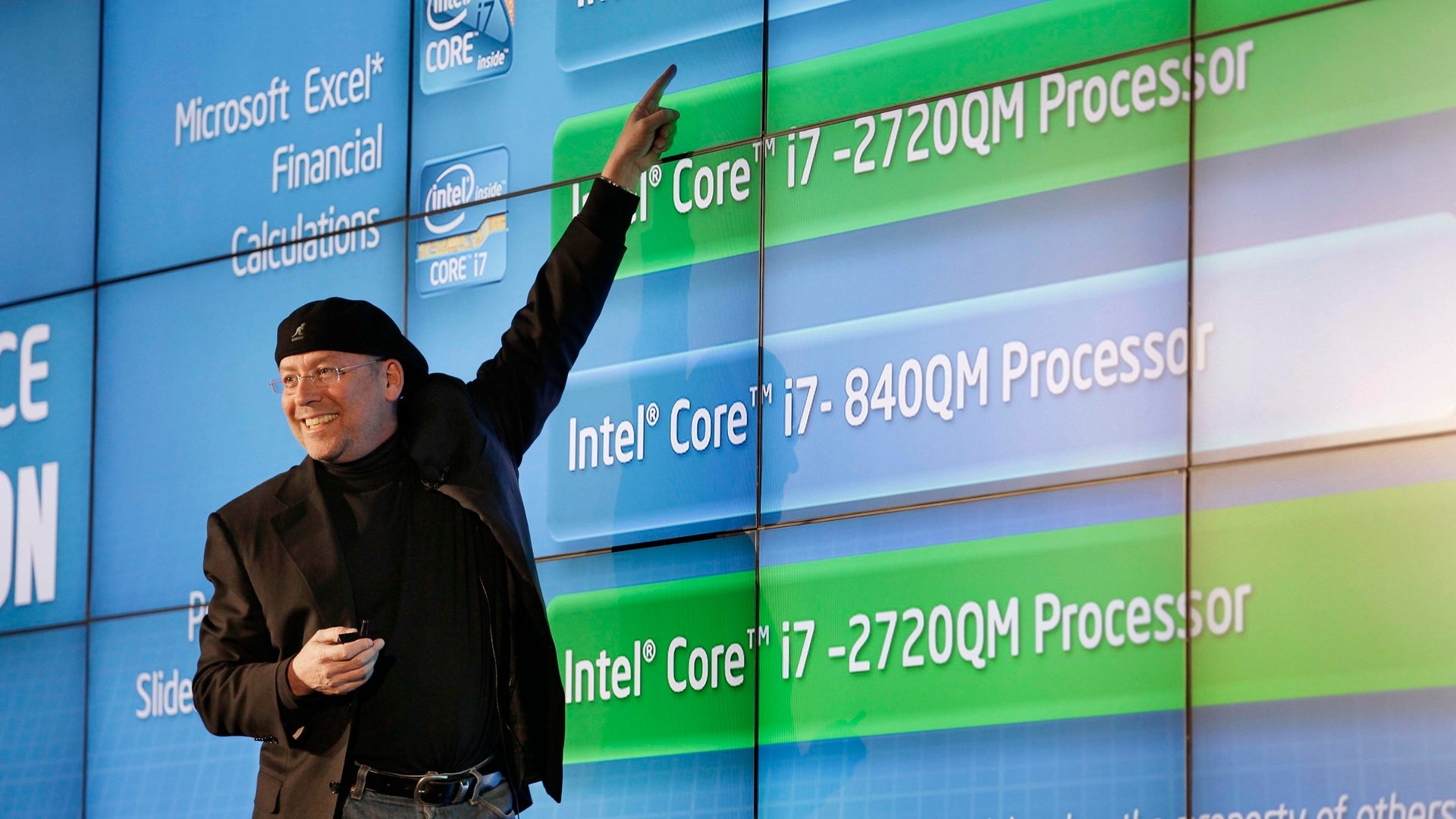

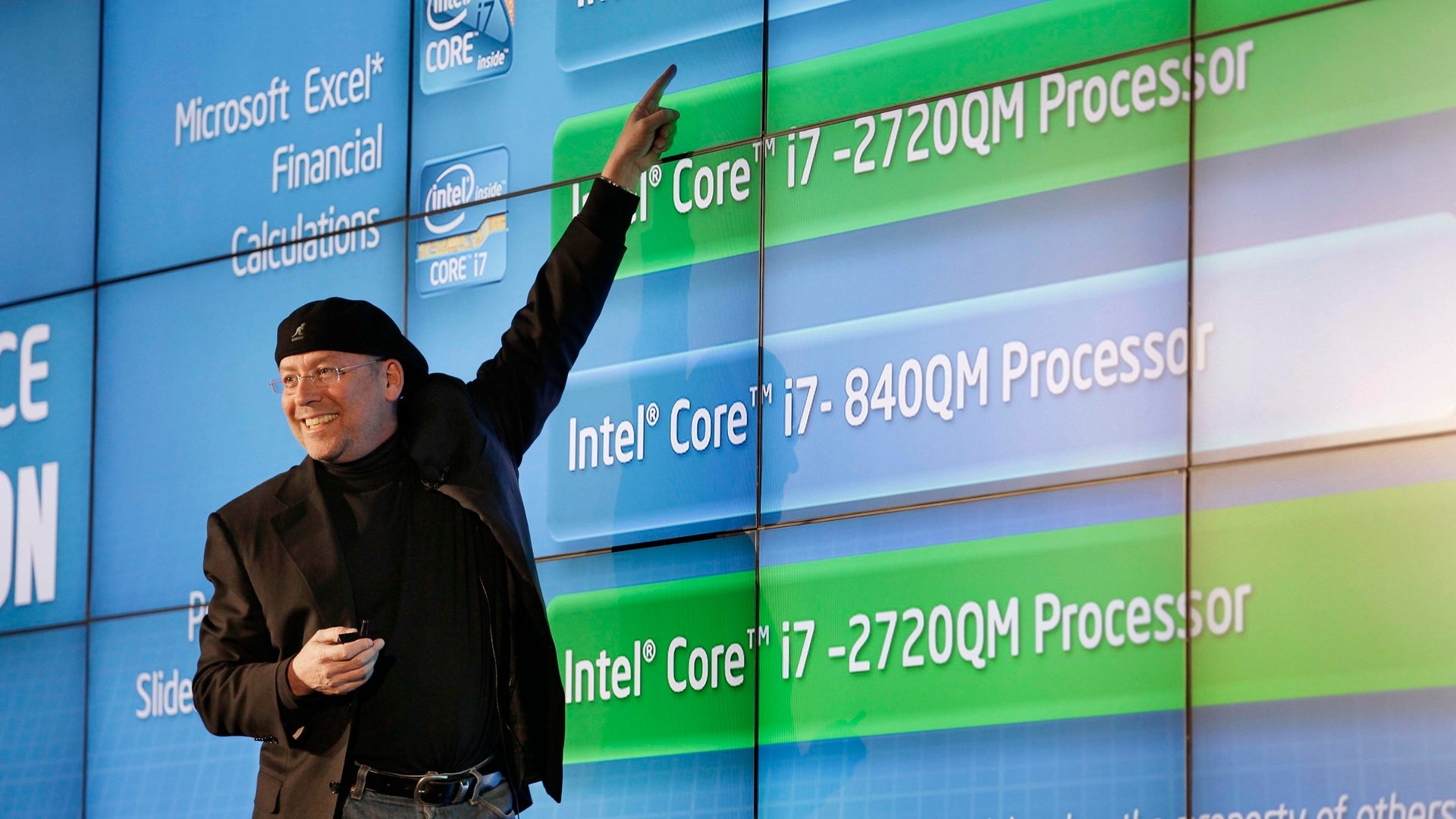

Which means the real dark-horse candidate for the position of Intel’s next CEO is the current head of Intel Israel, Shmuel “Mooly” Eden. (David “Dadi” Perlmutter, Intel’s current chief product officer, also came up through Intel Israel, and is considered to be one of Otellini’s possible successors; but he’s apparently Intel’s “Mr. Inside,” which means he’s good at running things but is seen as less suited to be the public face of the company.) In 2012, Forbes declared Eden one of its 10 brilliant technology visionaries. His team headed up development of Intel’s most advanced commercially-available microprocessor architecture to date. The one snag is that in January of 2012, after nine years in the US as vice president in charge of Intel’s PC business, Eden returned to Israel at his own request, to head up Intel Israel.

While head of the PC business at Intel, Eden also championed Intel’s effort to sell ultra thin, Macbook Air-like laptops called ultrabooks, which have sold only half as many units as Intel had hoped. That said, Eden is one of the few people at Intel capable of articulating a vision for the company as something other than an also-ran in the mobile chip space. In September, Eden told Israeli business site Globes that a future in which mobile devices are expected to power augmented-reality style eyeglasses, and process voice and gesture commands in real time, will demand the superior performance that Intel’s chips could be uniquely suited to provide.

Intel’s race to remain relevant is far from over. The company claims that its next generation chip architecture, called Haswell, will achieve a 20-fold improvement in performance per watt. If that’s true, it could finally put the company on an equal footing with ARM, which leads the market for mobile-device chips. Intel needs someone with a sense of urgency about mobile at the head of the company, and Eden, or someone else steeped in the combative, mobile-first culture of Intel Israel, could be just the right candidate.