The oil price collapse just claimed the world’s biggest shipping oil company

“You only find out who is swimming naked when the tide goes out,” Warren Buffett once quipped in one of his folksy shareholder letters.

“You only find out who is swimming naked when the tide goes out,” Warren Buffett once quipped in one of his folksy shareholder letters.

In other words, sharp, unexpected market downturns have a way of revealing less-than-top-notch market practices.

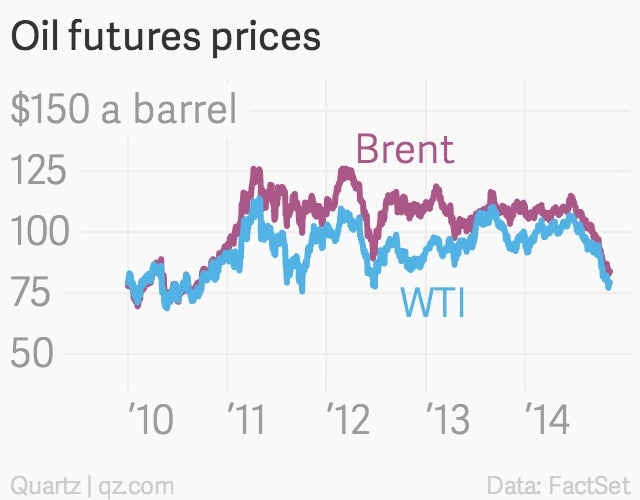

Such a vertiginous drop is now playing out in the global oil markets, as a resurgent dollar, slowing emerging market economies and surging US oil and gas production hit crude oil prices hard. (US benchmark oil prices are down more than 19% this year, and the European benchmark—Brent crude—is down nearly 24%.)

Clearly, not everybody saw this coming. Especially not the world’s largest supplier of “bunker,” or fuel for the global shipping industry, a Danish outfit by the name of OW Bunker. Last week, the company informed the public that its senior management had just learned of a fraud committed by senior employees of a Singapore-based subsidiary Dynamic Oil Trading. The company put initial estimates of that loss at roughly $125 million.

But beyond that, OW Bunker spotlighted shortcomings in its own risk management practices—essentially its fuel hedging activities—that had cost the company roughly $150 million, on a mark-to-market basis. Surprised by such gaping losses, creditors pulled back funding from the shipping giant, making continued operation impossible. OW Bunker filed for bankruptcy on Friday, leaving the global shipping fuel markets in disarray

Will there be broader fallout? No, not really. Some investors will take losses, as they should. But more broadly, the saga of OW Bunker underscores the intense difficulty anyone outside a trading desk has discerning the difference between “hedging”—that is taking market positions designed to mitigate risk—and proprietary trading positions aimed at boosting returns, by essentially gambling on market moves.

“We kept asking them if the hedging was a profit center or just clean hedging, and then it turns out they’ve been taking up massive market positions,” said Jesper Langmack, chief investment officer at Danish pension company PFA Pension, an investor in OW Bunker, told Bloomberg reporters. “When we asked before the IPO, we were left with the impression all they did was more or less clean hedging and now it turns out they were gambling.”

Identifying those differences and policing them is a problem neither investors nor financial regulators have managed to solve.