Where to focus if you want to fix traditional media

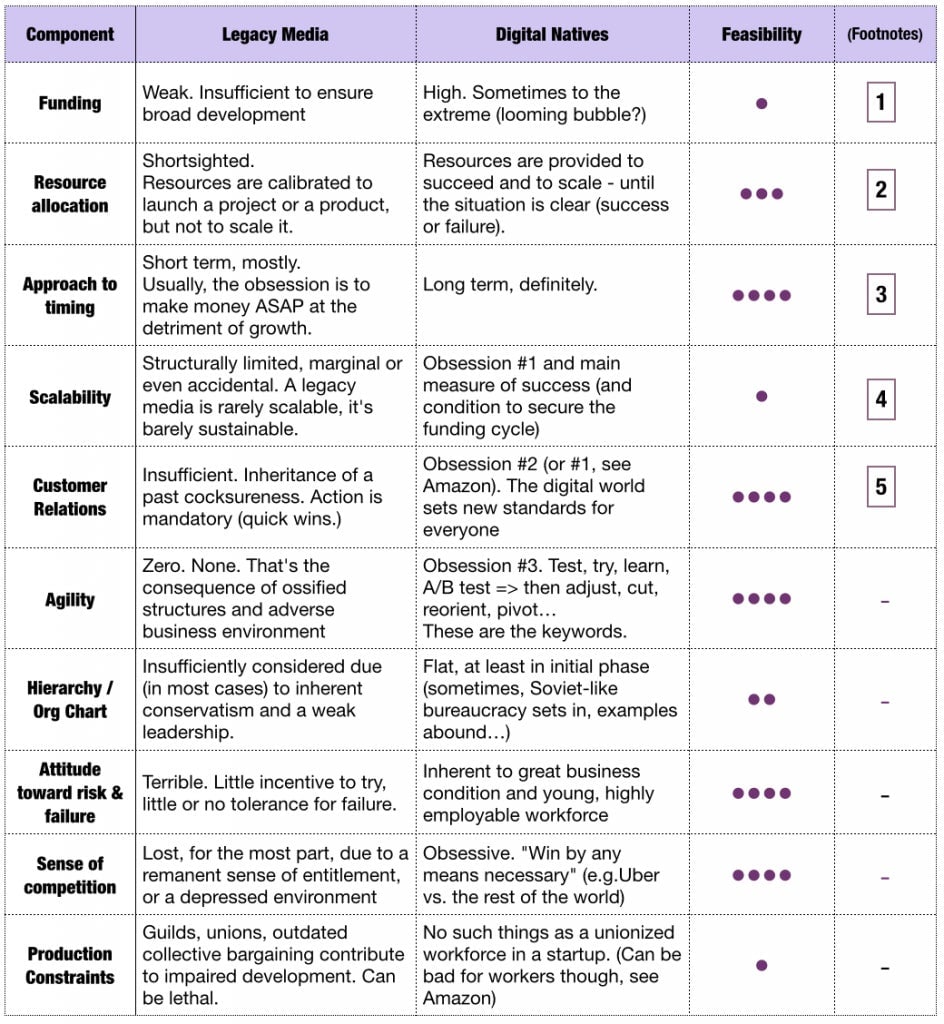

From valuations to management cultures, the gap between legacy media companies and digitally native ones seems to widen. The chart below maps the issues and shows where efforts should focus.

From valuations to management cultures, the gap between legacy media companies and digitally native ones seems to widen. The chart below maps the issues and shows where efforts should focus.

At conferences and workshops in Estonia, Spain, and in the US, most of my recent discussions ended up zeroing in on the cultural divide between legacy media and internet natives. About 15 years into the digital wave, tectonic plates seem to drift farther apart that ever. On one side, most media brands—the surviving ones—are still struggling with an endless transition. On the other, digitally native companies—all with deeply embedded technology—expand at an incredible pace. Hence the central question: can legacy media catch up? What are the most critical levers to pull in order to accelerate change?

It’s not a matter of a caricatural opposition between fossilized media brands and agile and creative media startups—the reality is far more complex. I came from a world in which information had price and cost; facts were verified; seasoned editors called the shots; readers were demanding and loyal—and journalists occasionally autistic. I came from the culture of great stories, intense competition (now gone) and the certitude of the important role of great journalism in society.

That said, I had the luck to be in the right place at the right time to embrace the new culture: at one of the small companies starting on a blank slate, with the unbreakable faith and systemic understanding that combine to create a vision of growth and success—all wrapped-up in the virtues of risk-taking. I always wanted to believe that the two cultures could be compatible—in fact, I hoped the old world would be able to morph swiftly and efficiently enough to catch the wave and deal with new kinds of readers—with a wider set of technologies and shape-changing competition. I still want to believe this.

In the following chart, I list the most critical issues facing media today, and pinpoint the areas of transformation that are both the most urgent and the easiest to address. My allocation of purple dots (feasibility) illustrates the height of hurdles facing large, established media brands.

Footnotes:

1. Funding: This is the main reason why newcomers are able to quickly leave the incumbent in the dust. When venture firms compete to provide $160 million to Flipboard, $61 million to Vox Media, or $96 million to BuzzFeed, the consequences are not just staggering valuations. Abundant funds translate into the ability to hire more and better qualified people. Just one example: Netflix’s recommendation system—critical to ensure both viewer engagement and retention—can count on a $150 million yearly budget, far more than the entire revenue of many mid-sized media companies. Fact is: old media companies in transition will never be able to attract these levels of funding due to inherent scalability limitations (it is extremely rare to see a legacy media corporation suddenly jumping out of its ancestral business).

2. Resource Allocation: Typically, the management team of a legacy media organization will assign just enough resources to launch a product or service, and hope for the best. This deliberate scarcity has several consequences: From the start, the project team will be in the fight/survival mode, even internally (competing with other projects or “historical” operations); secondly, in the (likely) case of a failure, it will be difficult to find the cause: Was the product or service inherently flawed? Or did it fail to achieve “ignition” because the approach was too cautious? The half-baked, half-supported legacy product might stagnate forever, without making enough money to be seen as a success, nor losing enough to justify a termination. By contrast, a digitally native corporation will go full throttle from day one with scores of managers, engineers, marketers and sufficient development time for tests, market research, promotion, etc. The idea is to succeed—or to fail, but fast and clearly.

3. Approach to timing. The tragedy for the vast majority of legacy media organizations is that they no longer have the luxury of long-term thinking. Shareholder pressure and weak P&L demand quick results. By contrast, most digital companies are built for the long term: Their management is asked to grow, conquer, secure market positions and then monetize. It can take years, as shown by many companies—from Flipboard to Amazon (which might have pushed the envelope a bit too far.)

4. Scalability vs. sustainability: Many reasons—readership structure, structurally constrained markets—explain the difficulty legacy media faces in attempts to scale up. At the polar opposite, disrupters like Uber or AirBnB, or super-optimizers such as BuzzFeed or The Huffington Post are designed and built to scale—globally.

5. Customer relations: Here, the digital world has reset the standard. All of a sudden, legacy media companies appeared outdated when it comes to customer satisfaction, from poor subscription handling to the virtuous circle of acquisition-engagement-retention of customers.

Many components remain extremely hard for established media companies to move–I personally experience that on a daily basis. But there is no excuse for not taking better care of customers, not rewarding the risk-taking of committed staffers, failing to assign resources in a decisive manner, or not instilling a better sense of competition.

You can read more of Monday Note’s coverage of technology and media here.