What would music sound like if record labels went out of business?

When you think about highly capital-intensive industries, music doesn’t usually spring to mind.

When you think about highly capital-intensive industries, music doesn’t usually spring to mind.

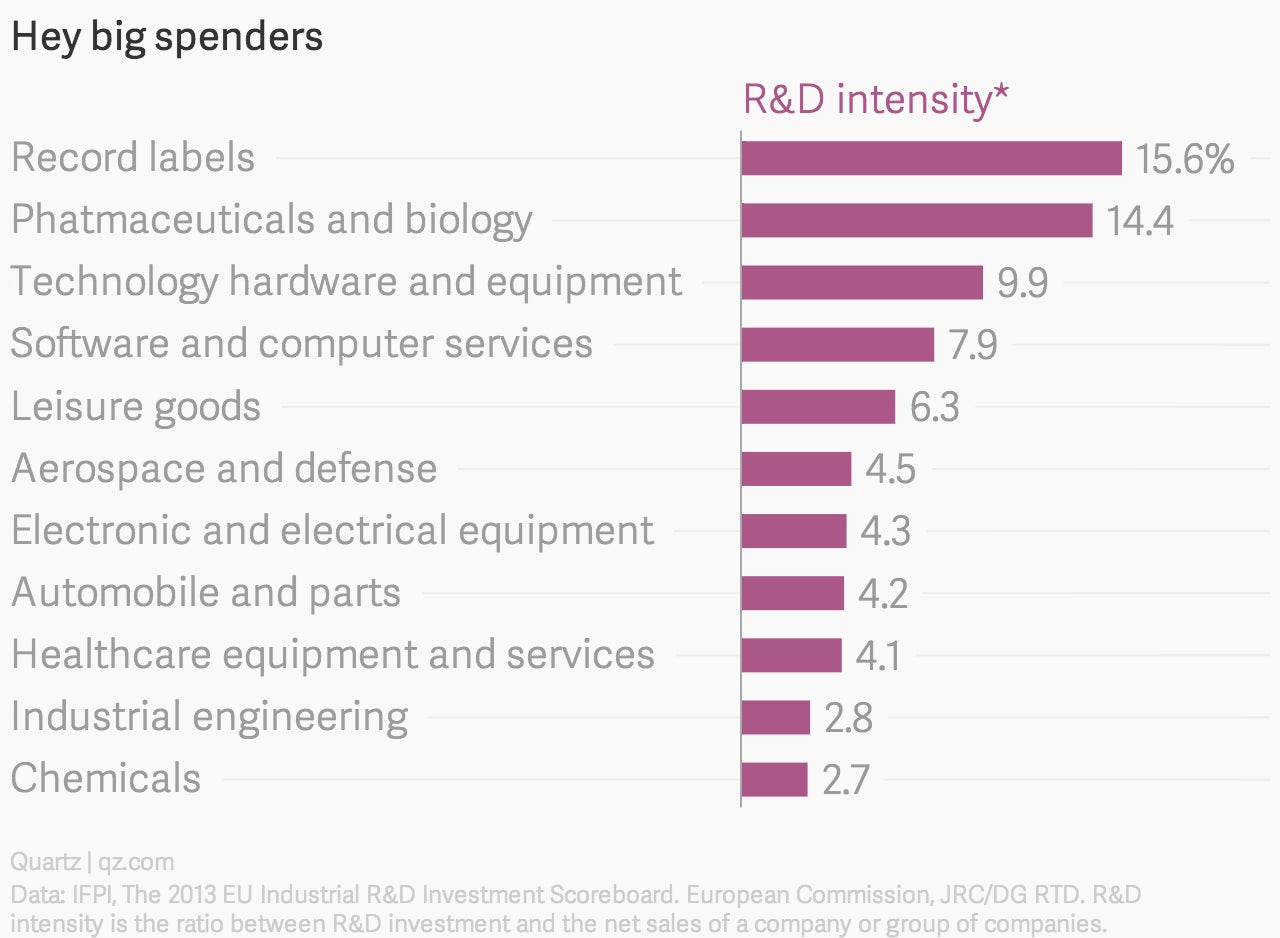

Yet billions of dollars are spent each year by record labels on scouting and developing artistic talent. In fact, as a percentage of revenues, labels spend more than many other investment-heavy sectors do on research and development.

Or so they say. The data in the above chart comes from a recent report by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, a trade association for record labels. (The music industry is notorious for its long history of dubious accounting methods but we’ll take this one on face value).

The report is important because it comes at a time when the relentless impact of the internet is forcing a major rethink about the future of the music business. Physical sales and downloads are in freefall as streaming music services (which generate smaller royalties for labels and artists) continue to grow in popularity, if not yet profits.

And if the royalty pie is shrinking, doesn’t it make sense to cut out the middleman? Why do bands or artists need a record label when they can build a viral following on the internet and reach fans directly though YouTube, SoundCloud, Pandora, and so many other avenues? How valuable is their financial support, now that recording music is so cheap to do, and funding for it can also be obtained through services like BandCamp and Kickstarter? Consider Macklemore, last year’s big music sensation, who had a number one hit and won a Grammy without the explicit support of a label.

Unsurprisingly, IFPI argues that labels remain essential.”Investors in music are vital to the work of artists,” Placido Domingo, one of opera’s “Three Tenors” and, strangely enough, the current chairman of IPFI, said in the report. “They are the risk-takers who win if an artist is successful, but lose if they are not.”

But historically, a lot of the “investment” in music has actually been borne by artists. Steve Albini, the legendary Nirvana and Pixies producer, for example, has railed against the “accounting trick called recouping,” a widespread practice where every cost associated with making and promoting a record is actually paid for not by the label, but by the band or singer, through forgone royalties.

Still, record labels spent $4.3 billion in 2013 on A&R (for artist and repertoire, which basically means scouting and developing talent) and marketing last year. But if all of this investment in music disappeared, what would we be losing, exactly? The bulk of the money from labels is spent on marketing and promotion, with only a fraction spent on actual recording. Any true music fan knows the most heavily hyped acts often are the most infuriating ones. Now labels are investing lots of time (and presumably money) analyzing data from services like Shazam and Spotify to try and better predict hits—a move that is actually making pop music even more repetitive and derivative. Without their interference, the recorded music that remains might very well offer the listening public an upgrade in overall quality.

Whether streaming music services will accelerate the decline of record labels or actually help them survive remains to be seen. But if worst comes to worst for the labels, it might not be so bad for music as an art form (or even a career choice). In any case, we might not have to wait too long to find out.