There are only 97 of these adorable porpoises left. In four years there will be none

Not much is known about the vaquita, a sleek mammal unique to the Sea of Cortez, other than that it is the smallest and most endangered porpoise in the world. Scientists believe there are only 97 vaquitas left, and if the population keeps declining at its historical rate of 18.5% a year, the species will be extinct by 2018.

Not much is known about the vaquita, a sleek mammal unique to the Sea of Cortez, other than that it is the smallest and most endangered porpoise in the world. Scientists believe there are only 97 vaquitas left, and if the population keeps declining at its historical rate of 18.5% a year, the species will be extinct by 2018.

Scientists are basing their estimates of the vaquita population (vaquita is Spanish for “little cow”) on sophisticated acoustic monitoring rather than visual sightings. Because they are shy and few in number, vaquitas have not been seen alive by many. More often they are found dead in fishermen’s nets.

In a recent article raising the alarm about the vaquita’s population crisis, the Washington Post’s Darryl Fears noted that the vaquita wouldn’t be the first marine mammal driven to extinction by humans—that unfortunate title goes to the Chinese river dolphin, which was declared extinct in 2006.

Somehow the global whaling industry managed to deliberately slaughter hundreds of thousands of whales over multiple centuries without actually extinguishing any species. By contrast, in the new millennium, cetaceans are dying out as a by-product of other industries. No one hunted the Chinese river dolphin, and no one is hunting vaquitas.

The Chinese river dolphin likely died out due to a combination of factors; if the vaquita goes extinct there will be one thing to blame: gill nets.

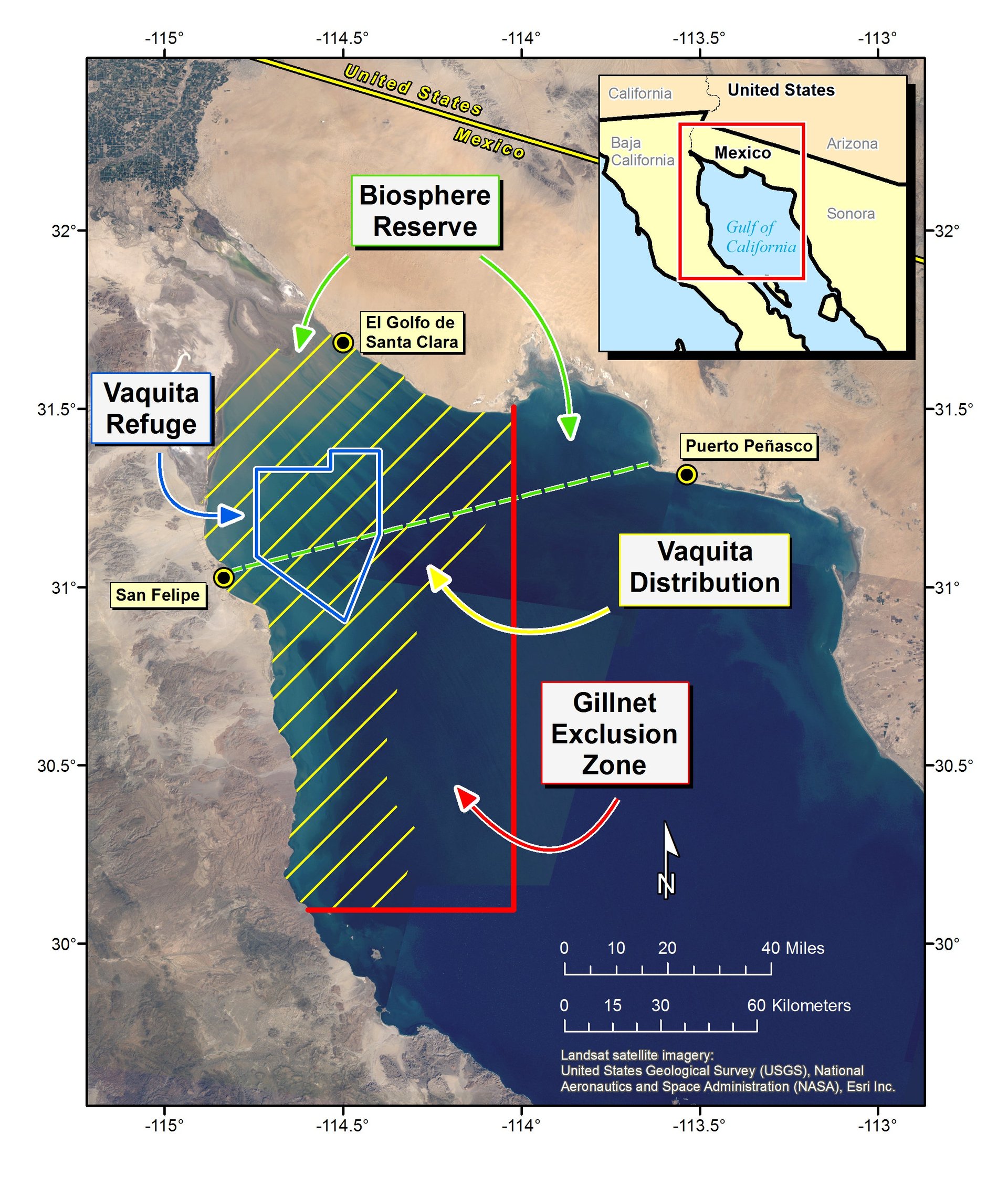

Marine biologist Barbara Taylor, who works for the US Southwest Fisheries Science Center and is a member of the international team that’s trying to save the vaquita, tells Quartz that nearly all of the fishing activity in the vaquita’s range—a small section of the upper Gulf of California, the body of water between Mexico’s mainland and the Baja California peninsula—involves gill nets.

The legal portion of this fishing activity involves casting nets for jumbo blue shrimp. The illegal activity, which has been surging in recent years, involves casting larger nets to capture totoaba, an endangered sea bass that’s about the same size as a vaquita and for which there is a lucrative black market. Totoaba bladders sell for as much as $5,000 a pound in China.

Porpoises are highly susceptible to becoming entangled in all of these nets, blindly swimming into them and, after a body roll or two, finding themselves unable to swim away or to reach the water’s surface. Like humans, porpoises (and dolphins and whales) cannot breathe underwater. If a porpoise gets trapped in a net, it drowns—and becomes “bycatch,” a superfluous and frequently unvalued part of a fisherman’s haul.

Mexico established a vaquita refuge in 2005, declaring a portion of the animal’s range off-limits to all commercial fishing. How well that rule has been enforced is perhaps reflected in what’s happened to the vaquita population since, and sheds doubt on how successful the total gill net ban that conservationists are pushing for would be anyway.

Taylor says the international network that’s trying to save the vaquita has been expecting Mexico to announce a two-year ban on gill nets in a larger swath of the upper Gulf—during which the government would pay fishermen, who would be sacrificing their incomes completely, and help them develop more vaquita-friendly fishing methods.

“We understand that the government of Mexico is working very hard on this,” says Taylor.

But time is running out for the vaquita.