American lawmakers will put their rubber stamp on global profit-shifting

All those Dutch sandwiches, double Irishes and Luxembourg, uh, lunchboxes that US multinational companies use to defer taxes and shift profits abroad are expected to be re-empowered today when the Senate votes to enact a one-year tax extension package.

All those Dutch sandwiches, double Irishes and Luxembourg, uh, lunchboxes that US multinational companies use to defer taxes and shift profits abroad are expected to be re-empowered today when the Senate votes to enact a one-year tax extension package.

Included in the package is a renewal of two breaks, one called controlled foreign corporation look-through and the other called the active financing exemption.

Together, they allow a US company’s foreign subsidiary to be invisible to the IRS for tax purposes, allowing them to defer taxes on “passive income” like royalties, interest and dividends that would otherwise be taxed.

That gives companies the ability to shift intellectual property overseas and construct complicated networks of loans between related subsidiaries, all to lower their tax bill.

“If there was not that exception, every time Apple paid royalties to its Bermuda subsidiary or Cayman Island subsidiary for using the Apple logo, and every time the Irish subsidiary paid those same royalties for using the Apple logo, it would immediately be taxable in the US,” says Rebecca Wilkins, the senior tax counsel at the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

These tax breaks—which together cost $80 billion over 10 years—are prized by the multinationals that take advantage of them to dramatically lower their tax rates, from Google to GE to Apple. Many companies note in their financial reports that failure to renew the breaks would significantly impact their earnings, and say they are necessary to compete in countries with lower corporate tax rates.

The existence of these loopholes has politicians in Ireland and other states that are criticized for their tax policy crying hypocrisy: It takes two to tango.

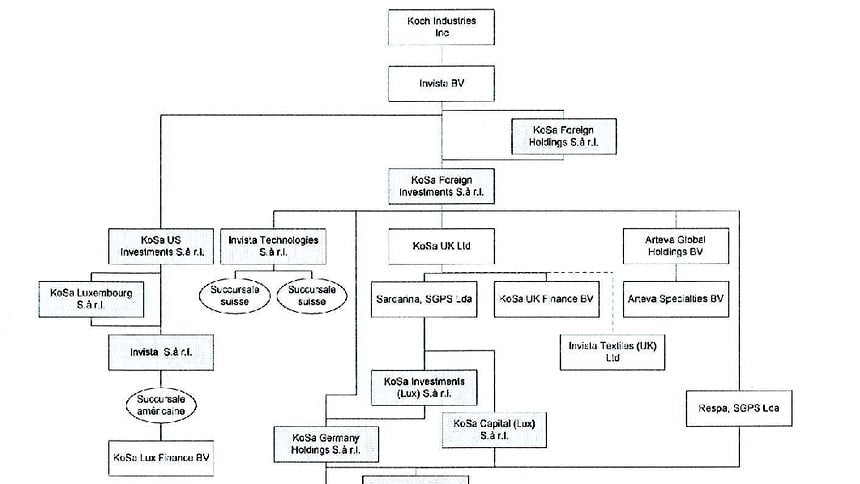

Sure, companies like Koch Industries, the petroleum conglomerate owned by major conservative donors David and Charles Koch, made back-room deals with Luxembourg to avoid corporate taxes.

But in the US, politicians from both parties will publicly sign off on offshore profit-shifting for any multinational firm, leaving domestic companies, individual taxpayers, and public borrowing to pick up the slack.