What China’s 2014 internet memes said about the country’s hopes and fears

In 2014, Chinese president Xi Jinping’s crackdown on corrupt officials and activists grew harsher. Pollution, food safety worries, the threat of a real estate collapse, and a slower growing economy remained high on everyone’s list of worries. And if you look closely, the memes and slang that have emerged from Chinese social media this year reflect some of those concerns.

In 2014, Chinese president Xi Jinping’s crackdown on corrupt officials and activists grew harsher. Pollution, food safety worries, the threat of a real estate collapse, and a slower growing economy remained high on everyone’s list of worries. And if you look closely, the memes and slang that have emerged from Chinese social media this year reflect some of those concerns.

One consistent theme seems to reflect a growing dissatisfaction with the country’s growing inequality, not just in terms of wealth but also politically and socially. ”Memes in China continue to show a preoccupation with members of the privileged upper class and those who are so unburdened as to live their lives in this way—[for example], the privileged pretty boy who is to be absolved from all worldly worries,” Marcella Szablewicz, an assistant professor in communications at Pace University in New York, told Quartz.

Daddy Xi

A nickname for Chinese president Xi Jinping, Xi dada “习大大,” or literally “Xi Big Big” first originated on China’s Weibo microblog last year. The moniker, which can also be taken to mean Uncle Xi in northern Chinese dialect, eventually broke through to the mainstream, becoming a common term used by Chinese state media and regular citizens.

The term gives Xi an air of accessibility—something he’s been going for since the beginning of his tenure as head of the Chinese communist party—but also a kind of paternalistic authority. ‘‘‘Uncle’ or ‘Daddy’ Xi,’’ after all, portrays him as something of a patriarch of the Chinese people, just as the emperor in imperial times was regarded as ‘father and mother of the people,’’Daniel Gardner, a history professor at Smith College in Massachusetts, told the New York Times blog Sinosphere.

The term is also being used unfavorably. Bloggers have started using a phrase, wuxing quedie, “to have everything but daddy” to refer to a lack of privilege or elite connections. (The phrase is a play on Chinese astrology and the earth’s five elements.) The phrase is similar to another meme that began in 2010, when the drunk son of a Chinese official hit two pedestrians in his car, killing one of them. When police came to arrest him, he allegedly yelled, “Sue me if you dare. My father is Li Gang.” One Weibo user, frustrated with government corruption, wrote in November, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of having everything but daddy.”

Little Apple

A retro-sounding dance hit by two former Youku stars, the Chopstick Brothers, is China’s version of “Gangnam Style.” The song xiao pingguo, or “Little Apple,” is irreverent, annoyingly catchy, and bizarre, with a politically incorrect music video featuring the two male singers, seemingly naked except for blonde wigs, as they pose as Adam and Eve, scenes from the Korean War, and a young girl’s plastic surgery gone nightmarishly wrong.

The song has inspired homage videos across China and is something of a point of pride for those seeking to exhibit China’s “soft power” influence over pop culture, which has lagged that of its neighbors like Japan’s J-pop or South Korea’s K-pop. The song has even been used as a recruitment video by the People’s Liberation Army:

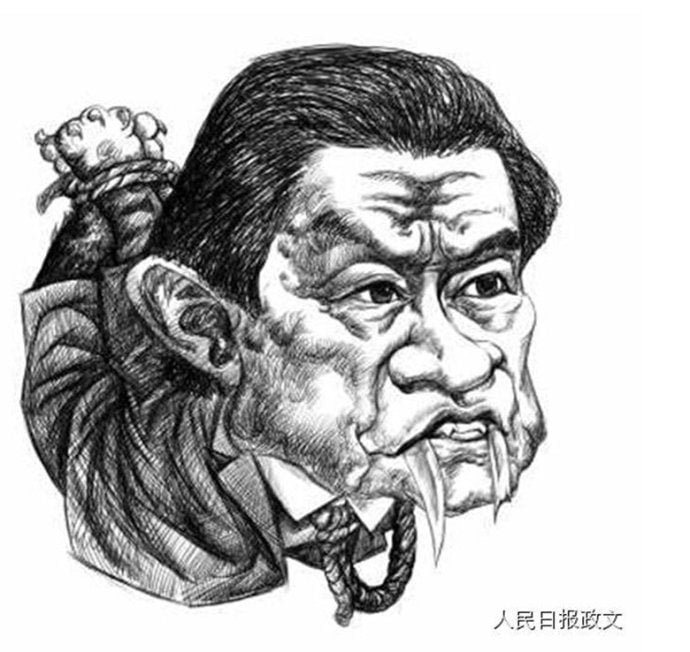

Master Kang

Master Kang, 康师傅, is the nickname of China’s former security czar Zhou Yongkang and comes from a popular brand of instant noodles. Zhou, one of the “tigers” in Xi’s anti-corruption campaign against both high-level and low-level officials, was detained in July . All references to Master Kang as well as his name were censored on Weibo, leading bloggers to refer to Kang as simply fangbianmian, “instant noodles.”

A few days before Zhou’s dismissal from the party, the People’s Daily posted various ways of cooking noodles, which Weibo users presciently joked was a veiled way to discuss the investigation into Zhou. One blogger wrote, “After cooking for all these months, the instant noodles finally seem ready!” Sure enough, Zhou was expelled from the party on Dec 5.

Zhou’s downfall is the biggest scandal to have rocked the CCP since Bo Xilai, former party chief in Chongqing, was convicted for charges of corruption and imprisoned for life. For Xi to go after Zhou, the party’s no. 3 during the previous generation of leaders, was unprecedented. According to some critics, it suggests that Xi’s anti-corruption campaign may just be a cover for a power grab at the upper-most echelons of the party.

Coincidentally, the fallen official shares the name as Hong Kong’s pro-democracy student protester and leader Alex Chow, or Zhou Yong Kang in Mandarin, whose name has also been censored in Chinese search results and social media.

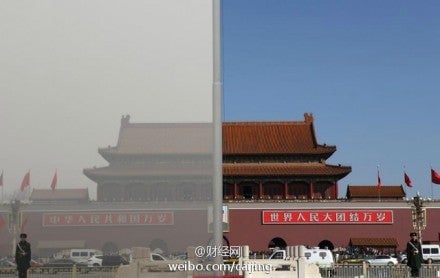

APEC blue

When China pulled out all the stops to ensure that leaders attending the the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation summit last month in Beijing would enjoy clear skies, Beijing residents criticized the effort, seeing it as evidence that Chinese officials have the capability to clean up the city’s noxious air pollution, but lack the will except when world leaders come to town. APEC has a new meaning among Chinese netizens: “Air Pollution Eventually Controlled.”

Now “APEC蓝” or “APEC blue” is used to symbolize the government’s unwillingness to do things for its own people, with a secondary meaning as anything that is beautiful but ephemeral. One Weibo user explained the term this way: “He’s not really that into you. It’s just an APEC blue.” Beijing smog, on the other hand, refers to something unattractive but long-lasting. ”He is so into you. It’s like a Beijing smog on a Saturday in December,” the blogger wrote.

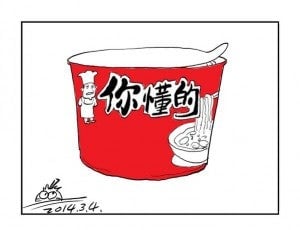

You know what I mean.

The short phrase ni dongde (你懂的) was first used by a government spokesman responding to a reporter’s question this March on whether Zhou Yong Kang (see above) was under investigation for corruption. While avoiding directly answering the question, the official essentially confirmed everyone’s suspicions, saying: ”Our serious investigation and punishment of party members and cadres, including some senior officials, indicates that what we stated was not empty words. I can only say so much so far. You know what I mean.” (Others translate it as “Enough said” or just, “You know.”)

The term quickly morphed into a way for bloggers to express anger or dissatisfaction with the government without explicitly saying what they mean. It is used in place of any comment that may be censored. For example, one blogger wrote, “Why can Beijing’s sky be blue during APEC? You know.”

BYOG: Bring-your-own-grain

“Bring your own grain,” abbreviated to just BYOG, or ziganwu (自干五) is a phrase bloggers reserve for pro-government propagandists who unconditionally support the Chinese government, and ask for no payment in return. The phrase draws a distinction between the “50 Cent Party” of online commentators who are allegedly paid 0.50 yuan for every pro-government comment, and those who write such comments for free—i.e. bring their own grain.

The Chinese government has tried giving the term a positive spin. In an article recently published in Guangming Daily, BYOGs are described as “the determined practitioners of the core values of socialism.” Still, most Chinese would rather not be seen as BYOG. One blogger wrote in response to the article, “ I also love my country, but why would I separate myself from the BYOGs? Because they confuse the country with the party. I will criticize forced demolitions, poisonous foods, medical systems while they just turn a blind eye to bad social situations.”