Will American companies spoil Europe’s party in Cuba?

Earlier this year, the European Union opened a new round of diplomatic negotiations with Cuba, aiming to strengthen the sometimes testy relationship between Brussels and Havana. Reaction to this potential deal was considerably more muted than the hoopla that accompanied the US announcement this week, for good reason.

Earlier this year, the European Union opened a new round of diplomatic negotiations with Cuba, aiming to strengthen the sometimes testy relationship between Brussels and Havana. Reaction to this potential deal was considerably more muted than the hoopla that accompanied the US announcement this week, for good reason.

Although the EU, led by Spain, is currently the communist island nation’s largest trading partner and external investor, the potential for free trade between Cuba and the US puts this in the shade. Some analysts reckon that removing the American embargo on Cuba could unlock trade worth more $10 billion a year between the countries. Last year, Cuba’s total trade was worth $20 billion, dominated by business with Venezuela’s sympathetic socialist regime:

Although relations between Cuba and the EU are strained, many individual member states—namely Spain, Cuba’s former colonial master—maintain a more or less normal bilateral relationship with the island. Diplomats in Madrid, Brussels, and beyond have welcomed the move towards normalizing US-Cuba relations, but for European companies that do business in Cuba, it is a mixed blessing.

France might lose a market for its wheat imports if the US agricultural juggernaut is allowed to sell to the Ohio-sized country just off the coast of Florida. But Spanish hoteliers could be in for big gains (link in Spanish)—indeed, Madrid-listed Meliá Hotels saw its shares soar in the wake of the US announcement. The company has operated on the island for more than 20 years, and now runs 27 hotels there.

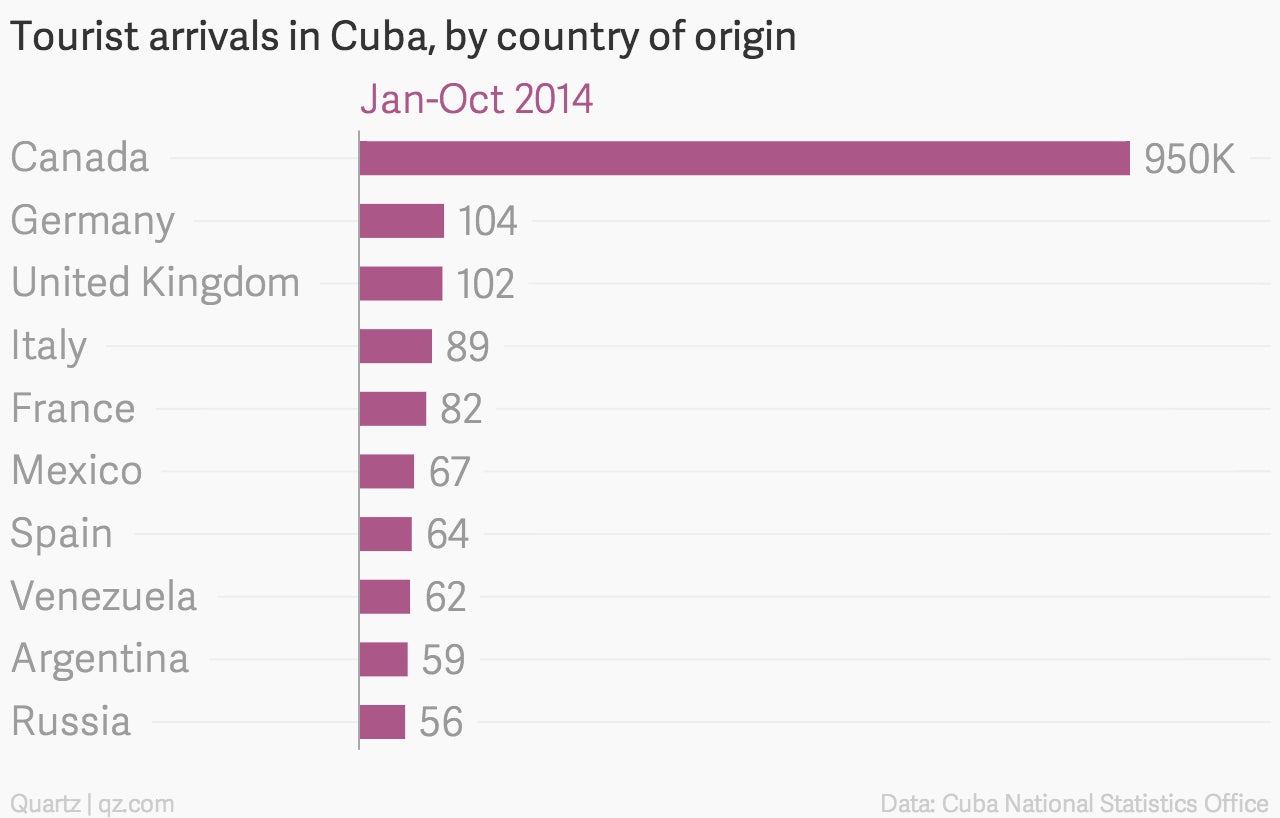

If American tourists are anywhere near as keen on Cuba as their Canadian neighbors, the opportunity is indeed enormous:

And even before a potential American influx, Cuba’s tourist industry could get a jolt from Canadians and Europeans rushing to experience the romanticized notion of a country untouched by modern commerce (and American holidaymakers).

Despite the risks for some European companies in Cuba getting muscled out by American rivals, on the whole “everybody is going to win,” Antonio Moreno, an economics professor at the University of Navarra in Spain, tells Quartz. Some of the current trade with Cuba might be a zero-sum game (American wheat replaces French wheat), but, mostly, a lifting of the US embargo will grow the overall pie, so even if the Europeans have to share with the Americans, the individual slices will still be bigger than before.

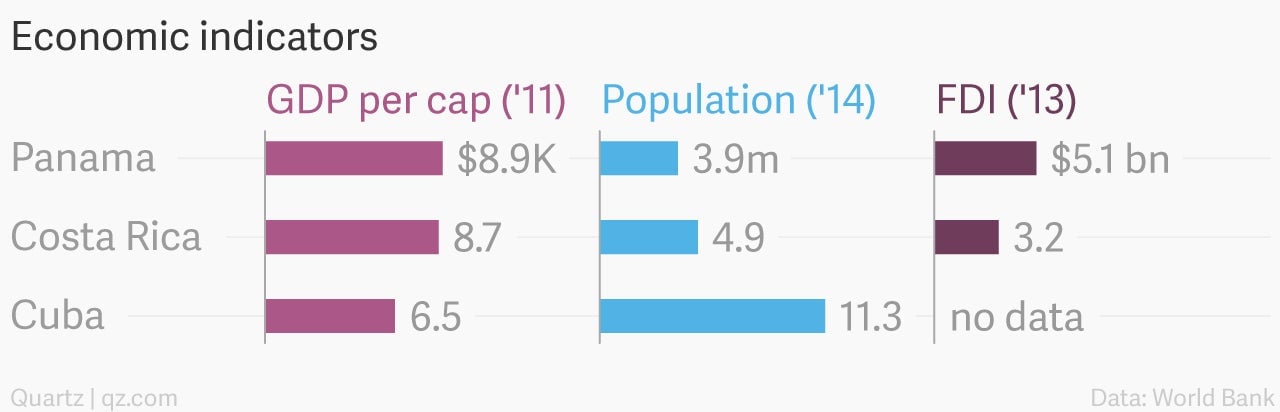

The best-case scenario, Moreno says, is that the US and EU will interact with Cuba in a similar way to Panama. Others have cited Costa Rica as a potential model for modernizing Cuba’s economy. Both of the Central American countries have liberalized their markets to varying degrees, adopting national strategies to boost tourism and creating special economic zones to attract companies.

Whatever the case, Moreno is bullish on Spain’s prospects in Cuba, which are improving at a particularly opportune time for the ailing euro zone economy. In addition to tourism, Spanish firms’ experience in real estate and transport infrastructure will come in handy if—or when—Cuba truly opens up. And Spain’s cultural ties to Cuba give it an edge over rival exporters in Europe.

But whether that’s enough to overcome stiff competition from eager American firms on Cuba’s doorstep is an open question. As an analyst told the Inter Press news agency even before Washington’s historic announcement, the signs suggest that there isn’t much time for European firms already in Cuba to dig in ”before the onslaught of business from the United States.”