Facebook is playing a cat-and-mouse game with Russian censors

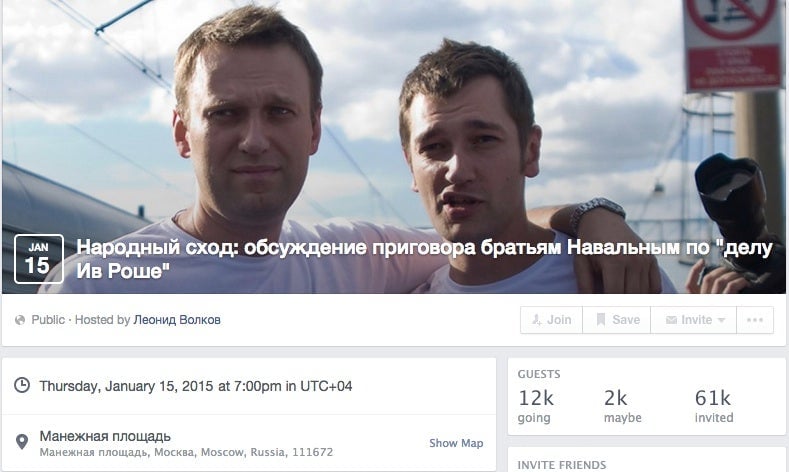

On Saturday (Dec. 20), Facebook blocked access to an event page in Russia. The page calls for a demonstration on Jan. 15, the day that opposition activist Alexei Navalny and his brother Oleg are due to be sentenced on what their supporters say are trumped-up embezzlement charges. The page (below), which had already attracted over 12,000 responses, is still online, but people in Russia can’t see it.

On Saturday (Dec. 20), Facebook blocked access to an event page in Russia. The page calls for a demonstration on Jan. 15, the day that opposition activist Alexei Navalny and his brother Oleg are due to be sentenced on what their supporters say are trumped-up embezzlement charges. The page (below), which had already attracted over 12,000 responses, is still online, but people in Russia can’t see it.

However, other versions of the page quickly popped up, including this one, which, I confirmed with friends in Russia, is still visible, and has over 17,000 people promising to attend.

Facebook declined to comment for this article, but the national telecoms regulator, Roskomnadzor, reportedly ordered the company (link in Russian) to block access to the page because it calls for an “unauthorized mass event.” A law passed last February allows the regulator to do this without a court order, and it’s been applied several times this year against both Facebook and its Russian competitor VKontakte. Facebook, like Google and Twitter, has to comply with local laws, and publishes information about the takedown requests it gets from governments around the world—though it’s come under fire recently for being too ready to comply. (Indeed, as some critics noted, it bowed to Roskomnadzor’s latest request even faster than VKontakte did.)

So why are the new pages still not blocked? Well, it seems Roskomnadzor can’t just tell Facebook to take down anything relating to the protest; it has to specify the actual pages, according to the law (link in Russian), which requires the regulator to send an offending website

…a notice, in electronic form in Russian and English, of a violation of the rules on dissemination of information, specifying the domain name and web address that identify the site on the network “internet” on which the information resides that constitutes a call to mass disorder, extremist activities, [or] participation in mass (public) events carried out in violation of regulations, and also identifiers of pages on the site on the network “internet” that permit the identification of such information… [my emphasis]

So as long as the authorities play within these rules, preventing new pages from popping up is going to be an endless game of a whack-a-mole. Roskomnadzor may be trying to come up with a better tactic.

But Facebook is also treading a fine line. On Jan. 1, a new law comes into force requiring internet firms to store data on their Russian users in Russia. Google recently said it was moving its Russia-based engineering team out of the country. The request to block the Navalny protest page may just serve as a reminder to Facebook that, increasingly, it operates in Russia only on sufferance.