This very scary chart reveals the risky business of China’s bull market

China’s out-of-the-blue stock market run-up may finally be screeching to a halt. The Shanghai Composite Index’s nosedive in the last half-hour of trading this week wiped out a 3.4% gain from earlier in the session, as fears of a worsening economic picture surfaced.

China’s out-of-the-blue stock market run-up may finally be screeching to a halt. The Shanghai Composite Index’s nosedive in the last half-hour of trading this week wiped out a 3.4% gain from earlier in the session, as fears of a worsening economic picture surfaced.

It was a rare, sobering moment for an index that has leapt more than 30% since October (and is still up 2% so far this year)—and a reminder of new vulnerabilities at work in the market.

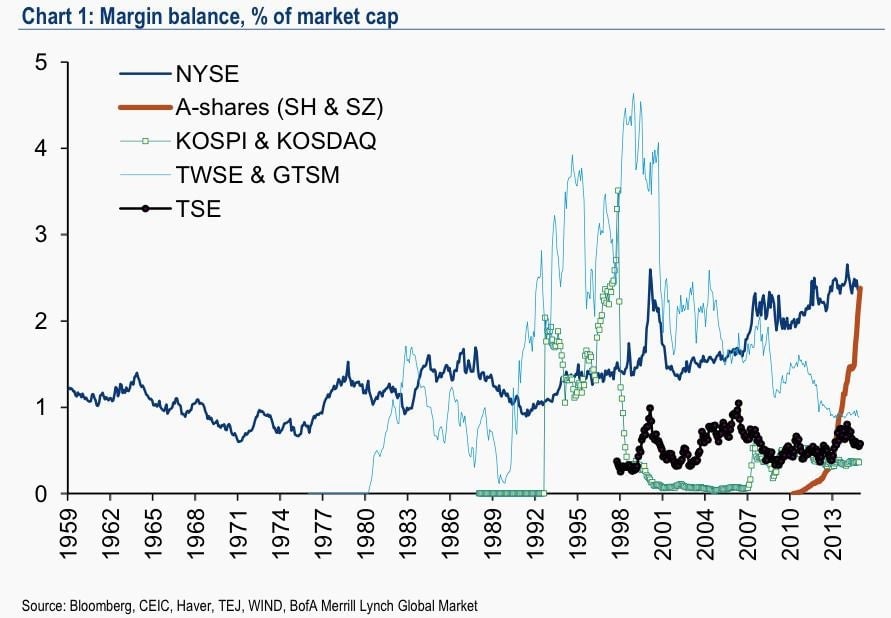

China’s corporate profits are probably not what has been driving China’s stock streak. They’ve been dismal; research firm GaveKal expects them to fall between 5% and 10% in 2015’s first half. Along with the government’s encouragement, a major factor—as we argued in December—is likely the recent rule change that now allows margin trading, meaning stock bets boosted by borrowing from brokers. But words don’t really do that observation justice. This chart, courtesy of David Cui, strategist at Bank of America/Merrill Lynch, shows the balance of margin-trading funds as a percentage of total market capitalization on different exchanges:

That nearly vertical line in burnt umber shows the ratio of the margin trading balance to the total value of China’s two markets, in Shanghai and Shenzhen. With leveraged funds making up about 2.4% of overall market cap, that puts China about even with the New York Stock Exchange. But as Cui points out, it took the NYSE 13 years to reach that point; China’s investors managed the feat in just 17 months.

That speedy take-up could prove problematic. Chinese investors aren’t experienced enough with margin trading to know what happens when the market drops, says Cui. When falling markets force investors to sell out of their margin positions, they find themselves suddenly owing much more than the money they initially invested. While China requires a relatively high downpayment ratio, says Cui, that inexperience could cause an overreaction that makes liquidity disappear quickly.

That would be bad for the market, of course. It could also be disastrous for the economy, where tight liquidity makes sudden cash squeezes dangerously easy to trigger.