The psychology of big personalities will determine our global course in 2015

The world looks more unruly than in recent memory: oil prices are in free fall, and stock markets are gyrating; brutal rebel armies have created broad swaths of mayhem—in eastern Ukraine, northern Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria; the US is disinterested in taking charge, and no recognized figure has stepped in to take its place.

The world looks more unruly than in recent memory: oil prices are in free fall, and stock markets are gyrating; brutal rebel armies have created broad swaths of mayhem—in eastern Ukraine, northern Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria; the US is disinterested in taking charge, and no recognized figure has stepped in to take its place.

Against this backdrop, conspiratorial and self-interested actors have shaken up what seemed decided. Last year, we learned from Russian president Vladimir Putin that European borders can still be changed by fiat, and from Saudi Arabia we discovered that hitherto mighty OPEC can be crumpled up like a wad of paper and tossed in a bin.

Momentum alone ought to signal that 2015 will bring new confusion, fresh surprises, and more shredded history. But while the year will deepen our disorientation, and include horrendous tragedies like last week’s massacre in Paris, the surprises are by-and-large likely to be smaller.

The main driver of events will be unusually high stakes in countries that are the domain of outsized personalities (see below.) The Big Personality Rule for predicting geopolitical outcomes that we’ve outlined before explains that the presence of certain individuals in an event—a Churchill, a Stalin, a Lyndon B. Johnson—can utterly change the dynamics. In the case of today’s big personalities, look for the stakes as they perceive it—the desire for power and legacy—to produce the most consequential action of the year.

Some examples:

—US president Barack Obama desperately wants to leave office as a progressive and hero on a grand scale.

—Putin is working to nail down his abiding aim to be remembered on the same Russian plane as czars Peter and Catherine.

—Iran’s Ali Khamenei faces an unprecedented challenge to the 36-year-old revolution that he is sworn to uphold.

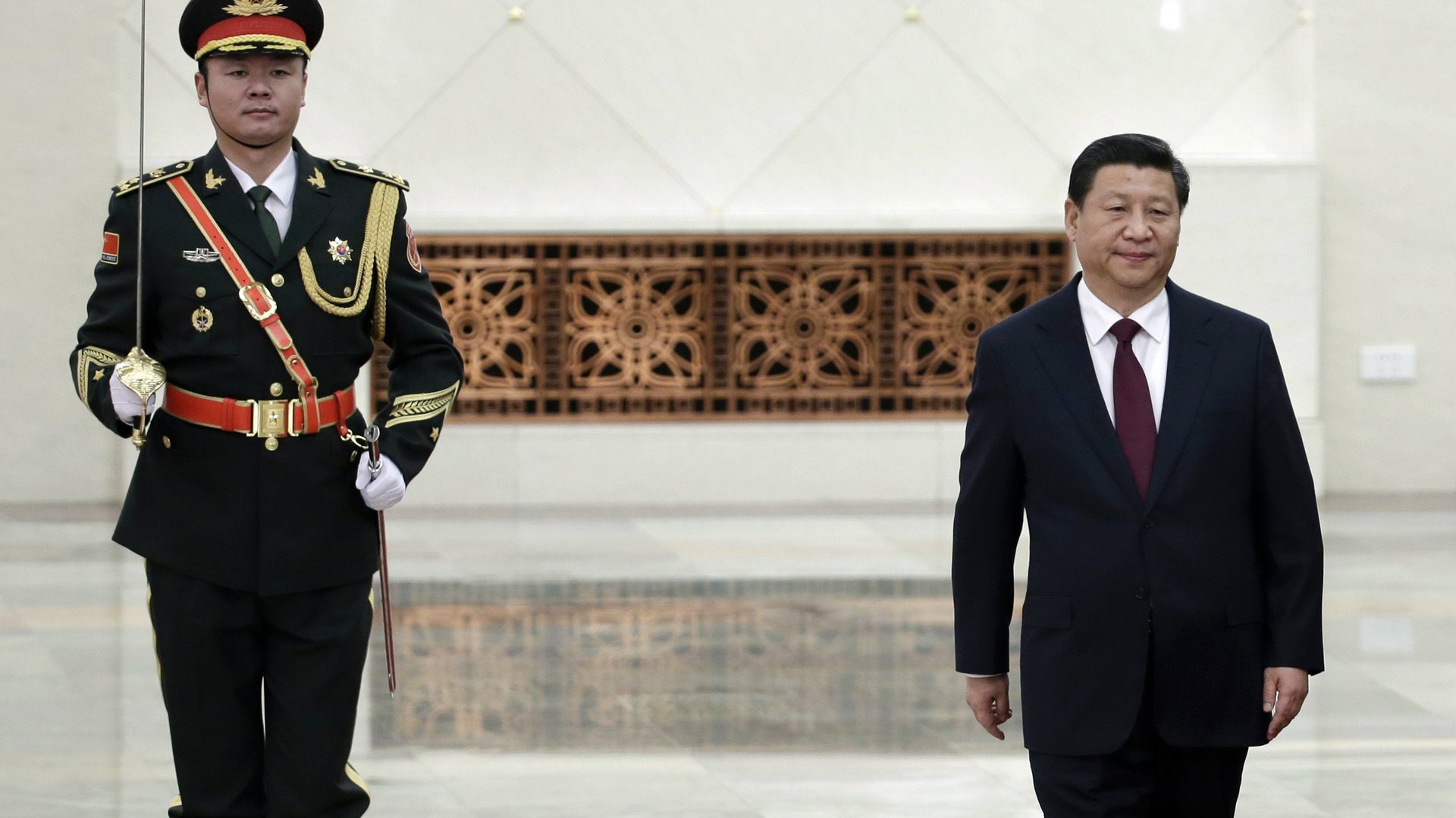

—China’s Xi Jinping is on a path to eclipse Deng Xiaoping as his country’s most powerful and consequential post-revolutionary leader.

The forces acting on these world leaders will pull them in competing directions. Below, we examine which route they are likely to choose. As always, we are guided by the Quartz algorithm, 12 common-sense rules of thumb that illuminate the direction of geopolitical events. (You can read more detailed descriptions of the 12 rules in our original discussion of them.)

Oil will roil everything

There’s a very good chance that we have already seen more or less the average price of oil for the year—$50 to $60 a barrel. (I’ve made a wager with colleagues on the energy beat that Brent crude will end 2015 at $57.75 a barrel.)

We have already weighed in on how these prices will shake up geopolitics this year: In brief, OPEC’s richest countries—Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar—will suffer a hit, regardless of their current game faces, but have no choice other than to see their low-price strategy through to its conclusion. This strategy seeks to drive higher-cost rival producers out of the business—those in the US shale oil patch, Canadian oil sands, and Brazilian deepwater crude. The strategy is guided in large part by the Stay in Power Rule, which states that political leaders, regardless of their locality, will do what it takes to keep their jobs. In this case, the longer that shale producers in particular are permitted to build market share, the greater the threat to incumbent drillers in the Persian Gulf.

But along the way, these rich countries will be bruised by the loss of income and draining down of their prodigious cash reserves. Saudi Arabia in particular claims it’s prepared to withstand cut-rate prices for up to five years, but this reeks of bravura: If sub-$90 oil persists for two years—and possibly before—look for much nervousness and a change of tactics even in Riyadh.

As for the poorer OPEC members—such as Iran, Nigeria, and Venezuela—they have barely any cash reserves about which to become agitated. Nigerian officials specifically have observed the Getting Rich Rule all these years, feeding from the trough while large swaths of the population have gone without electricity.

But now that the commodity boom is over, Staying in Power will guide the behavior of these lesser OPEC producers. Low oil prices and tightened government spending can lead to public unrest, in line with the Injustice Rule, which explains the public reaction under conditions of perceived economic and judicial unfairness. Look for a combination of reactions: an initial impulse by governments to crack down on unrest, but eventually—the longer that prices stay low—a move to greater fiscal discipline and economic diversification. What not to expect: utter collapse. This is because, even in times of desperation, nations tend to Muddle Along.

Obama will rise to his full height

Since his party was trounced in the mid-term polls in November 2014, we have witnessed a very different Obama. He is no longer the conciliatory politician of the first six years of his presidency. In his first term and after, the Republican Party deliberately rejected all or most of Obama’s initiatives with the zeal of True Believers. He accused them of ignoring the results of the elections he won; they replied that their very presence in office was proof that the people wanted them to gum up the works. Now, the tables are explicitly turned. It is the Republicans who want to make a splash. You see where this is going: It is payback time.

In a twist on the Law of Averages, Obama intends to do big things by executive order—such as permitting five million illegal immigrants to stay in the US, and setting out to finally close the Guantanamo detention center. (On the latter, look for Obama to transfer sufficient numbers of prisoners this year that the prison’s closure becomes a fait accompli.).

At the same time, Obama will continue to veto as much of the Republican agenda as he feels like. In both cases—the executive action and vetoes—Obama will be looking at his legacy.

On the international stage, too, Obama intends to get done what he can. The world seems particularly unmanageable at the moment, but in the post-election period he has already imposed new sanctions on Russia and North Korea, normalized relations with Cuba, and signed a climate change accord with China. Can he do a deal with Iran (see below)? Help Israel and the Palestinians to settle their differences? Marginalize ISIL? Look for him to push harder on all three.

Since much of this agenda is abhorrent to Republicans, they will respond in the courts. There is precedent for that—under president Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Supreme Court rolled back several of his signature New Deal initiatives. Some of Obama’s most cherished actions may face the same fate. If so, that would be another twist on the Rule of Averages.

Khamenei will allow a nuclear deal

Iran started out the year by conveying conflicting futures: president Hassan Rouhani suggested that he was prepared to go further to meet the demands of western-led negotiators seeking to prevent Tehran from obtaining a nuclear weapon. Iran’s aims are not “linked to a centrifuge, [but] … to our heart and to our willpower,” he said on Jan. 4. To throw off hard-liners, he proposed handing the issue to a public referendum. It was a nervy move considering that Rouhani lacks the power to schedule referendums and that not he but supreme leader Khamenei holds decisive influence over security concerns.

Khamenei was not amused. On Jan. 7, he rebuked Rouhani, whose remarks he called “wrong and uncalculated.” Rather than trust the US, Iranians, Khamenei said, should immunize themselves against sanctions. In other words, moderation may make economic sense, but the old guard isn’t necessarily prepared (paywall) to achieve such gains at a possible cost of giving up the revolution.

This clash in the power structure is not new. In our 2013 and 2014 forecasts, we predicted an Iran deal (we went 50-50; the former was correct and the second not). Our reasoning in both was that Khamenei, while being a True Believer whose judgment is driven by ideology, was also subject to the Staying in Power and Local Power rules. He is cognizant of the 2009 and 2013 presidential elections, in which the Iranian public made plain its unhappiness with the status quo and desire for reforms, and would not want to risk a new uprising. He would also be guided by the Precipice Rule, which states that nations and their leaders will squawk and threaten but ultimately stop short of actions that could send themselves over the precipice.

Yet last year, as discussed above, the Conspiracy Rule confounded this reasoning. That is, Khamenei is so blindly furious with the US that he may not recognize his own conspiratorial mind nor even be able to clearly appraise the terms on offer to him (or that, after 2016, a new US administration, particularly if it is Republican, could make a deal much harsher.) In addition, he knew that, absent a nuclear deal, Iran would not collapse—the Muddle Along rule would carry it through.

But there is something new—it is low oil prices. In November, when Iran stepped away from an accord, sub-$100-a-barrel prices were only a bit over two months old. Economic suffering was notional. But six months from now, the hurt will be tangible and perhaps, from the street, even loud.

So we return to our original thesis. It is a close call—Khamenei is as much a True Believer and a conspiratorial leader as almost any on the planet; he will go down to the wire in hopes that oil turns around. But, while prices may rise from their current level by July, we expect no spike, as discussed above. As Iran’s big personality, only he can made the big decision, and on behalf of his legacy and the security of the regime, we believe he will take the plunge: western-led negotiators and Iran will sign a nuclear deal this year.

Putin will spend a quiescent year

Bilious resentment poured out of Putin last year. He seethed not only because of the west’s transparent plot to unseat him and thereby consign Russia to the status of weak servility, but also because of its centuries of determination to fracture the Slavic country. Will the world be treated to a continuation of Putin’s pity party, in line with the broad definition of the Conspiracy Rule?

Some of our most prolific observers of Russia say that, yes, we will—forecasting Russia, says one of them, requires no more than utter pessimism. While the oil price plunge is forcing Putin to dip into hard-won cash reserves to prop up banks and businesses, he won’t seek to diversify the Russian economy and avert such economic crisis in the future, they say. He understands, they say, that Russia cannot compete with China in the realm of products (even though the downest-on-their-luck states do just that with their cheap labor pools), so he will simply ride out the down cycle. Meanwhile, he will avail of other tools up his sleeve in order to survive.

Ahem. Quartz has spent time in Russia, too, and we have doubts about the doubters. We do not play down the appeals of the Injustice Rule (Putin embracing a dynamic that more typically describes the behavior of ordinary people and situations such as the Arab Spring, and not the whinging of strongmen).

But we observe evidence that Putin is changing course in line with the Rule of Averages. This rule explains that, generally speaking, even the most extreme leaders and situations tend over time to peter out and move closer to the middle.

In Putin’s case, he could seek to top his 2014 behavior—he could send incognito green men into a Baltic country, for instance, play cyber havoc with a western target (more on that below), or wreck the Iranian deal that we describe above. If he is so inclined, there is time for all that and more later. For now, Putin faces a predicted 5% economic contraction for the year and the prospect of propping up Russian banks and companies with billions of dollars in debt payments coming due in 2015 and 2016. Toward cushioning the blow, Putin can’t do much about oil prices, but he can back off in Ukraine, and possibly get western sanctions lifted so that these enterprises can roll over their debt to European banks.

And that is what already seems to be in motion. On Dec. 27, Putin agreed to provide coal and electricity to Ukraine without advance payment. The same day, Moscow-backed separatists in eastern Ukraine exchanged a total of 350 prisoners with Kiev. We don’t see Putin going warm and fuzzy with Ukraine, the West, or his critics at home. But look for a far more cautious Putin who for starters finds a modus vivendi with Kiev, does nothing to hinder an Iranian deal, and even works behind the scenes to achieve one.

European sanctions may be softened but not those from the US, which will be governed by Local Politics—in the runup to 2016 elections, neither Obama nor Congress will risk the political backlash of being perceived as soft on Russia.

Xi will play big geopolitics

For four years, China has been a forceful actor in the world, making its presence felt from the South China Sea to Latin America, from Africa to Canada. Yet, all along, it continued to observe Deng’s dictum rejecting involvement in the politics of the countries with which it intersected.

Until now. In December, China stepped into Afghan politics, hosting a delegation (paywall) of Taliban officials and offering to provide a venue for negotiations with the Kabul government. This was explained by the Mountain Rule, which states that future superpowers begin to feel their oats prematurely and to act in an outsized manner. We see this as an inflection point. Look for leader Xi to cross the former political redline when, as in Afghanistan, he perceives strong Chinese strategic and economic interests are in play.

One possible additional venue: Venezuela, which has been a major toehold for China in Latin America; Caracas owes China $20 billion, and just took on $20 billion more. If Xi perceives that president Nicolas Maduro is on the verge of default, one could imagine Beijing stepping in to try to modulate Maduro’s erratic economic and political behavior in order to salvage the investment.

For now at least, China’s transformation seems likely to play out less menacingly than some have feared. In line with the Rule of Averages, Xi is moderating the extremes of Beijing’s aggressive behavior, as seen last year in a naval standoff with Vietnam.

In a little-noticed illustration, Xi on Jan. 7 pulled back in what had been the biggest recent confrontation of all between Beijing, Japan and the West—the Chinese stranglehold on rare-earth minerals. The decision seemed to demonstrate a desire to keep confrontation within check and not violate the Precipice Rule.

Geotechnology will come into its own

Last year was a maelstrom (paywall) of cyber warfare, from the pilferage of nude celebrity photos, to an attack on US merchandisers, to the assault on Sony. In short, cyber-warfare morphed from an exotic crime into regularized havoc with broad geopolitical ramifications. It introduces a new arena of geopolitics that we’ll call geotechnology.

Consider the breadth of the battlefield: Last year, hackers disrupted not just the victims cited above, but also a German steel mill and the casinos empire of magnate Sheldon Adelson. The attacks appeared to come from Iran, Russia, and North Korea, or possibly contracted freelancers—this much was educated guesswork. But the underlying dynamic was not—it was a twist on the Mountain Rule. It was actors on the margins, wishing to attack real and perceived mountains.

A number of rules could be germane to what comes next—the Local Politics Rule (with an organizer conducting a local cause); an amalgam of the True Believer and Injustice rules (with righteous actors lashing out at perceived enemies); or the Getting Rich Rule (culprits working for money.)

But what is clear is that the age of geotechnology will continue into 2015. Edward Snowden, who has lived in Moscow since leaking a trove of NSA secrets in 2013, argues that US intelligence should no longer emphasize cracking the secrets of smaller nations, but focus on defending the US cyber infrastructure.

Whatever one thinks of Snowden, his advice seems sensible. Among the potential targets needing defense are transportation, public utilities, and industrial systems.

Then there are batteries, another area of tech with geopolitical impact. GM begins the year with an official announcement Jan. 12 that it will take on Tesla in the production of a reasonably priced electric car that can go 200 miles on a single charge. The price—in the mid $30,000s—and traveling distance are important news. Look for 2015 to be the year that electrics move from a niche and squarely into the mass market. When they finally do, they will have the same geopolitical punch as low oil prices: oil-producing countries will have another challenger impinging on and threatening their turf.