It’s the media’s duty to republish the controversial Charlie Hebdo cartoons

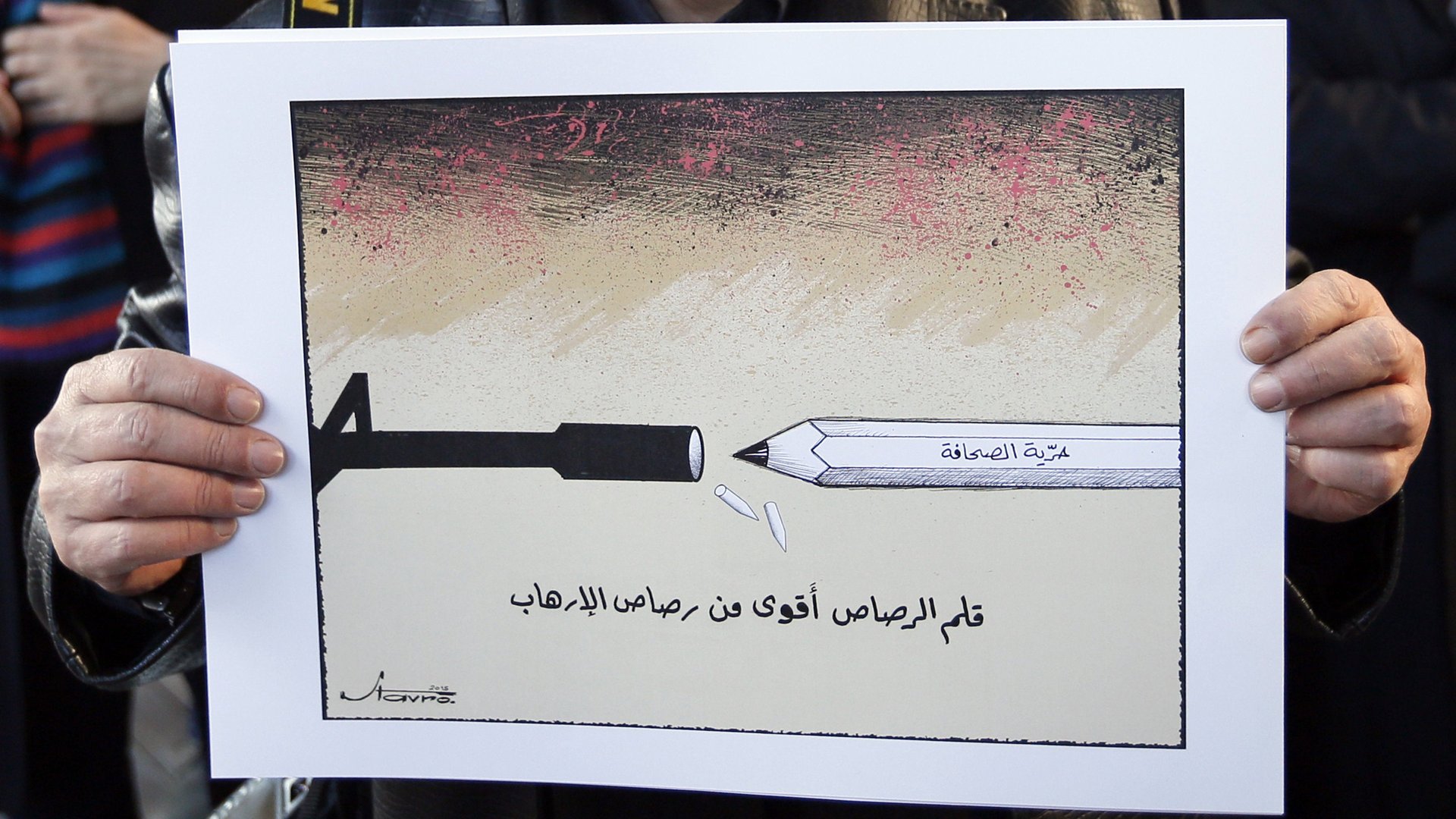

About four million people marched Sunday across France in support of the 17 people killed in last week’s terror attacks. France is in a state of shock—the emotion is overwhelming, and the concern is growing as everyone realizes the size and depth of French Jihad networks.

About four million people marched Sunday across France in support of the 17 people killed in last week’s terror attacks. France is in a state of shock—the emotion is overwhelming, and the concern is growing as everyone realizes the size and depth of French Jihad networks.

While anti-Semitic attacks are unfortunately not a novelty in France, the retaliation on news media now takes the shape of professionally executed targeted assassinations. From now on, every media publishing offensive cartoons could suffer Charlie Hebdo’s fate. This is what happened to the Hamburger Morgenpost—firebombed this Sunday at 2am—exactly the same way Charlie Hebdo was four years ago.

France is not through with terrorist attacks. Friday evening, hours after SWAT teams stormed the kosher supermarket, the interior minister painted a grim picture of what’s ahead. “Over the recent months,” he said, “One hundred and three legal procedures have been initiated against terror cells, involving 505 people. There is not a single day in which I don’t take an operational decision regarding these issues.” More broadly, law enforcement estimates the threat at 1,200 “potential jihadists.” Several hundreds of them are under surveillance.

On the investigative site Mediapart, former counter-terrorism magistrate Gilbert Thiel said this:

Our problem, today, is that we went from 100 people to monitor in 1995 to 1,000 today. Between 12 and 20 law enforcement people are needed to keep track of one single individual on a 24-hour basis. Then we discover that the individual’s friends and relatives need to be monitored as well. At some point, we’re swamped.

To make the problem worse, counterterrorism experts quoted in Le Monde believe that 3,000 to 5,000 Europeans are fighting in the name of Jihad in Syria and Iraq; half of them are said to be identified after their departure and 20% are coming back, most of them brainwashed and not in a sunny mood.

Unlike the September 11th era of terrorism where attacks were engineered from abroad, today Al Qaeda and ISIL are very good at exporting terrorism into the social fabric of Western countries, encouraging the emergence of widespread, independent micro-cells with people quite effective at using kalashnikov rifles and explosives.

Let’s come back to the cartoons. I think news media that balk at republishing caricatures of the Prophet Muhammed are ill-advised. This is the worst time to yield to self-censorship and political correctness.

I wasn’t personally a fan of Charlie Hebdo. Ten years ago, it published an article saying, in substance, that the newspaper I was editing at the time—20 Minutes—with its three million readers and a staff of 80 fine reporters and editors—didn’t deserve to exist. The Charlie Hebdo author said that he’d prefer that people read nothing rather than a free newspaper—a genre that was unanimously loathed by the “noble” paid-for news media at the time.

Charlie was then under the editorship of a sectarian character, a friend of Nicolas Sarkozy’s wife Carla Bruni—a fact that helped him land a managing job at Radio France for a quickly forgotten tenure. At the time, the written part of Charlie wasn’t the paper’s best. But its cartoons were. Definitely. I deeply believe that satire and caricatures are an important component of free speech; because of this, Charlie has every right to exist and I really hope it will survive. (Frankly, I doubt it as most of its great talents have been killed.)

Among many comments I read, I spotted an editor saying that he doesn’t feel like putting his staff at risk by re-publishing Charlie’s cartoons.

I can’t disagree more. As unpleasant it is, I think it’s part of the job.

In February 1989, I was a young reporter at Libération when a fatwa was issued in Iran by then-leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini against Salman Rushdie, author of The Satanic Verses. The first reaction of Libération was to publish a large abstract of Rushdie’s novel. Needless to say, in the months afterward, we operated under serious police protection. To every staffer of the paper, this was obviously the right decision to make (we were actually quite proud of our editors.) Later, when the Danish newspaper Jyllands Posten published 12 cartoons that trigged scores of violent demonstrations across the world, Libé republished most of the cartoons.

In his style, Charlie Hebdo went many steps further. Its editor Stephane Charbonnier (“Charb”) was put on a hit-list by the Yemen-based pro-Jihad magazine Inspire, along with other writers and cartoonists.

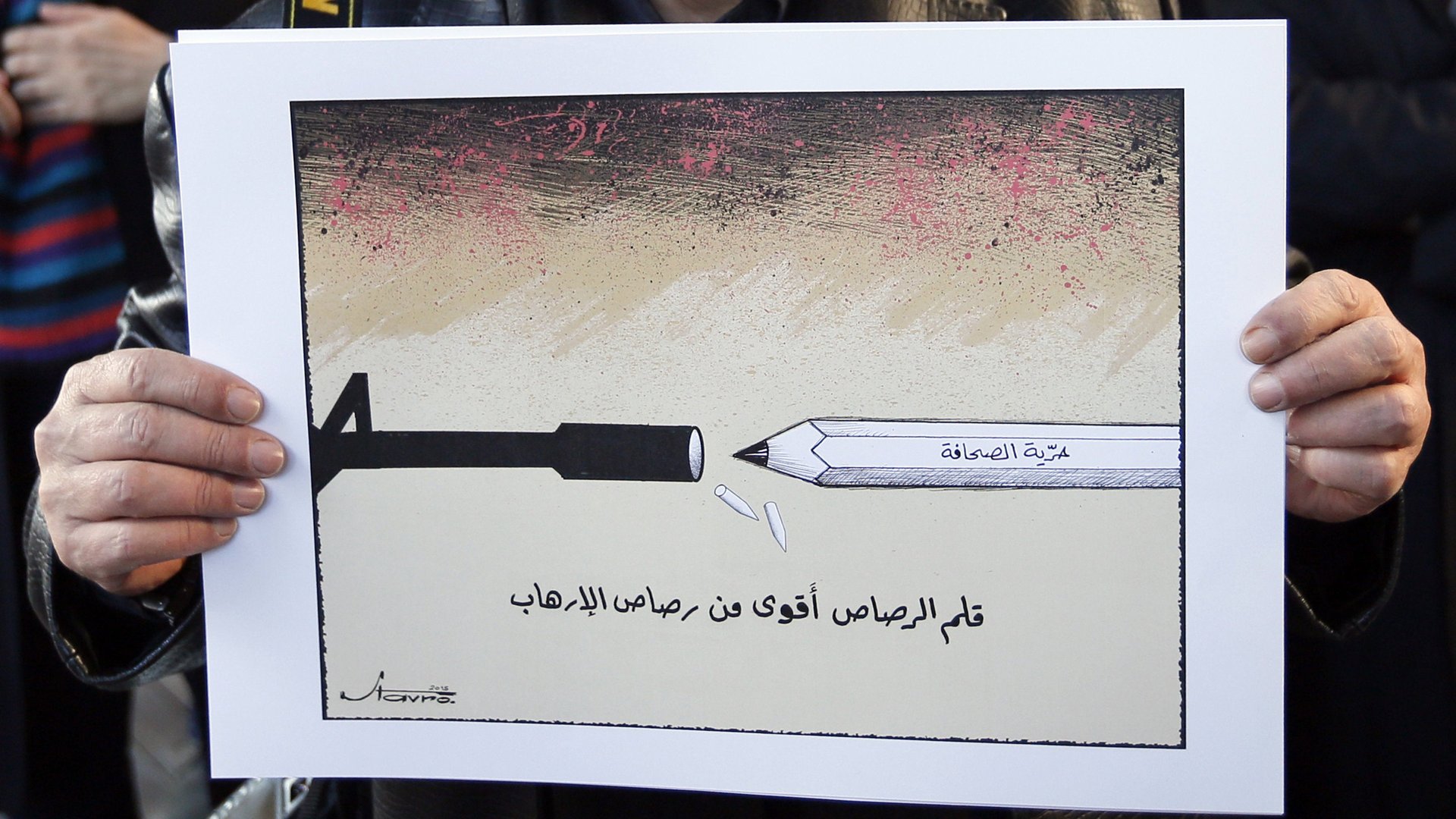

In 2011, the paper published a satirical issue titled “Charia Hebdo,” “guest edited” by the Prophet Muhammed with this front page:

Quickly after, the magazine was firebombed, and UK and American newspapers published this pixelated image:

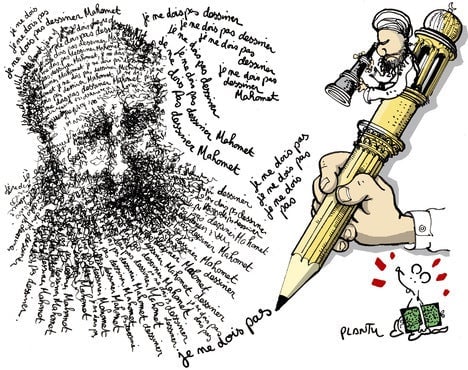

And last week, The Telegraph, among many others, opted for a carefully cropped version of the photograph of “Charb” holding the controversial front page:

Certainly not the finest hours of the Anglo-Saxon press.

That’s why I felt bad for The New York Times when I read its convoluted justification for censoring itself. (BuzzFeed and The Huffington Post did publish the drawings.)

Publishing controversial caricatures is a mandatory mission for news media.

First, because it’s newsworthy—readers must see for themselves what this is about without the filtering of virtuous editors who give themselves the right to decide what their audience should or should not see.

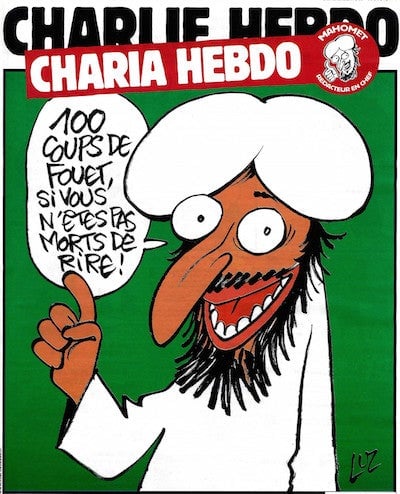

Second, because when it comes to caricatures, the line between fun, sharp, and excessive is blurred. It is completely subjective. In 2011, Le Monde cartoonist Plantu published this drawing:

He might be seen by devout Muslims as crossing a religious boundary. (Plantu is one of France’s most talented and courageous cartoonists.)

Would the New York Times, The Telegraph and others pixelize Plantu’s work as well—under the pretext that some might find it offensive and retaliation might ensue?

Then what about real journalistic work, investigative series, video reporting, and documentaries about such sensitive issues? If one day extremists decide to use rifles and explosives against journalists and documentary makers, to what extent will these cautious news organizations refrain from picking up great—but dangerously hot—stories ?

Over the last days, we’ve seen pundits stating that the millions of people marching in France are the proof that extremism failed. They are wrong. The battle has just begun, and it’s not the time to balk.

You can read more of Monday Note’s coverage of technology and media here.