Putin has friends on Europe’s far right and left (but mostly right)

Diplomatic talks between the European Union and Russia are at an impasse. The supposed ceasefire between Ukrainian government forces and pro-Russian separatists in the east of the Ukraine has been routinely broken—the latest bloody episode being a stray rocket that struck a passenger bus, killing 12, earlier this week.

Diplomatic talks between the European Union and Russia are at an impasse. The supposed ceasefire between Ukrainian government forces and pro-Russian separatists in the east of the Ukraine has been routinely broken—the latest bloody episode being a stray rocket that struck a passenger bus, killing 12, earlier this week.

A durable ceasefire is a key condition of the EU relaxing its financial sanctions on Russia, which would relieve the ruble’s ongoing collapse and improve Russia’s otherwise bleak economic outlook. Given the ongoing violence, the sanctions don’t look likely to be lifted any time soon.

For good measure, the European Parliament is considering a resolution condemning Russia’s “aggressive and expansionist policy” today. There will be dissenters on both the left and right. Or, rather, on the far-left and far-right.

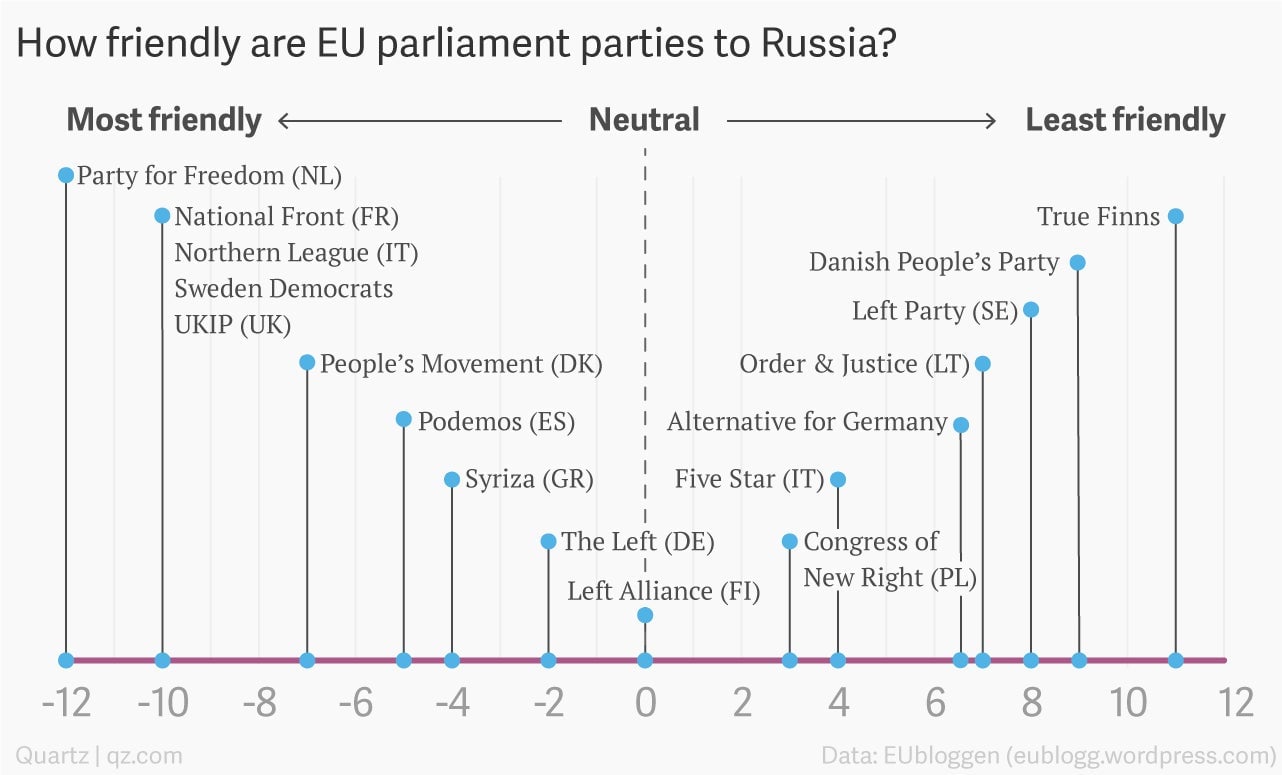

Patrik Oksanen, a Swedish journalist, ran the numbers on recent European Parliament votes on Russia-related issues, focusing on the “euroskeptic” parties on the far-right and far-left that have made big gains in the chamber recently. His ”Russia Index” ranks 17 euroskeptic parties in Brussels, many of which also command a fair amount of power back at their national parliaments:

The index is based on a dozen different votes over the past six months, recording whether a majority of a party’s delegates voted for or against certain measures—mainly around greater EU cooperation with Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova.

The Dutch Party for Freedom, led by Geert Wilders, who has said that the EU is to blame for the crisis in Ukraine, gets a perfect score of voting in a Russia-friendly way. Just behind it are fellow far-right outfits like UKIP in Britain and France’s National Front, both gaining followers in their home countries with anti-EU, anti-immigration platforms.

So far, there hasn’t been any significant fallout at home for these parties from any perceived friendliness to Russia, even after the National Front took out a loan from a Russian bank. The same goes for far-left upstarts like Spain’s Podemos and Greece’s Syriza, which also lean on the Russia-friendly side of the index, but are leading polls at home ahead of national elections this year.

At the other end of Oksanen’s scale, the far-right True Finns and Danish People’s Party have made a habit of consistently voting against Russia’s interests. That’s despite party platforms that may not look so different from other euroskeptic rightwingers, like the Sweden Democrats, which have a starkly different voting record on Russia.

Members of some of these parties explained their positions to Oksanen, which he posted on his blog, with some noting that they took issue with unrelated issues bolted onto the Russia-related motions they voted on.

This makes things tricky for Russian president Vladimir Putin when he goes looking for allies in the EU. These parties are all keen on dismantling the EU from the inside, so their actions may reflect a genuine opposition to closer cooperation with Ukraine, or to rebuking Russia, but they might simply also be down to their opposition of everything that the EU does.