If you talk to enough people at the Finnish mobile startup Jolla, at some point it occurs to you that the company it most resembles is Apple. Not the Apple of today, which is basically a half-trillion-dollar supply chain with a design appendage, but Apple back when it was Steve Jobs obsessing over the creation of the Macintosh, which was radical in its focus on the user. In demos, at least, Jolla’s decidedly different new mobile operating system (OS), called Sailfish, looks that good.

Sailfish, Jolla insists, will become a legitimate alternative to the Coke and Pepsi of smartphone platforms: Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android. Microsoft would like to accomplish the same thing, and has spent billions trying, with limited success; it has already cut back production for the new tablet running its latest OS, Windows 8. So what makes this group of fewer than 100-odd Finns, most of them refugees from the sinking ship that is Nokia, think they stand a chance?

“China… is the most dynamic smartphone market—it’s really booming,” said Sami Pienimäki, who runs sales at Jolla, at the company’s Nov. 21 unveiling of its new OS in Helsinki. “There is 80%-100% year-on-year growth.” (At least one projection suggests that the number of smartphones in China could grow by 150% in the next year alone, to 500 million devices.)

Jolla cannot possibly take on Google and Apple head-to-head, and it doesn’t plan to. Rather, the company, which is rapidly becoming a Finnish-Chinese hybrid with headquarters in both Helsinki and Hong Kong, and an R&D operation in a yet-to-be-named location in mainland China, plans to nurture and grow an entirely new mobile “ecosystem”—meaning the phones, the operating system that runs on them, and the apps that run on that. And it plans to do it in China because that is the one market producing first-time buyers of smartphones fast enough to give such a scheme a chance.

In order to get its operating system and, eventually, Jolla-branded phones, in front of enough Chinese, the company has partnered with the largest mobile chain retailer in the country, D.Phone. Not only will D.Phone sell Sailfish-powered phones through its 2100 outlets; it is also part of the Sailfish Alliance, a group of software and hardware companies that will all be able to add standards and code to the open-source OS.

The deal with D.Phone isn’t just a feather in Jolla’s cap; in some respects, it’s the reason it exists. It represents an early commitment from an established player with reach but no devices of its own, and a built-in market for what would otherwise be an even more hugely risky proposition.

A radical user interface

Jolla CEO Marc Dillon believes that both iOS and Android are, essentially, boring technological dead-ends where innovation has gone to die. And if you cruise YouTube for the various hands-on videos demonstrating the Sailfish OS, you begin to get a sense of what he means. Visually, Sailfish doesn’t seem very radical, but the mechanics of how people interact with it are.

Sailfish is designed to acknowledge that most people use their phones for several things at once these days. The phone’s home screen can be filled with up to 9 concurrently running applications. (Contrast that with an iPhone, where, save for things like playing music, applications are paused when a user switches from one to another.) And they can all be controlled without even “opening” them. Rather, each “application cover”—which is a large rectangle on the phone’s home screen—has its own interface.

The basis of this is “swipe” gestures, a convention borrowed from the Nokia N9, a one-of-a-kind phone that Nokia developed in alliance with Intel and released in 2011. It ran on a unique operating system called MeeGo, which is a direct ancestor of Sailfish. (Most of the Jolla team came from Nokia and previously worked on MeeGo, and while Jolla has no financial ties to the company, spiritually it’s a spin-off.) Swiping from one side of a tile or the other will, for instance, skip tracks if it’s a music player, or flip through contacts if it’s the address book.

While in some ways Sailfish superficially resembles the Windows phone, which has a home screen full of “live tiles” displaying information from various apps, the tiles’ only other function in Windows is to open the app when you tap them. The Jolla team seems to have asked itself: What does the user want to accomplish, and what’s the smallest number of taps required to accomplish it?

“I believe that when people try [Sailfish] and use it for a few minutes, it’s going to resonate with them,” says Marc Dillon, CEO of Sailfish. “It enables things that are much more different than on other devices. It makes them effortless.”

A radical business model

Ease of use is one part of Jolla’s plan. Market reach is another.

In China, things work a little differently than they do in rich countries. Retailers like D.Phone, for example, wield outsize influence over the rest of the mobile device market. In the West, cell-phone carriers generally pay the handset-makers part of the cost of a phone in return for being the exclusive carrier for that particular device. In such a market, a new phone based on an OS that nobody has heard of doesn’t stand a chance because the carriers won’t take a gamble on it; they might not recoup their outlay. In China, however, the retailers buy handsets and charge customers full price for them. The way carriers compete for exclusivity is to offer retailers and their customers the biggest possible amount of free airtime.

That means that if D.Phone decides it wants to take a chance on a new device, carriers can’t really veto its decision. And D.Phone, and presumably other retailers, has much more incentive than the carriers do to offer something truly different, because otherwise the only way it can compete with other retailers is on price.

“In China, many families are coming to the point where they’re either saving for their first real smartphone or they’re ready for the next one,” says Dillon. “They really do want to stand out and have something a bit different.” Android dominates in China, capturing nearly 80% of all Smartphone sales. Apple’s iPhone stands out and is different, but it’s also hugely expensive for a country in which the average yearly household income is still only about $9,000.

Coke, Pepsi… and Red Bull?

Andreas Constantinou, managing director of Mobile Vision, a telecoms consultancy, isn’t buying the Jolla story.

“It’s impossible for anyone to compete with the duopoly of Google and Apple,” says Constantinou. The mobile market, at least in rich countries, is winner-take-all. Users don’t care who makes their phone, he argues; they care whether or not it will run the apps they want. Developers, meanwhile, only want to create apps for the platforms with the most users. The result is that Apple and its fast follower Google, which pioneered the smartphone app store, have made it too hard for newcomers to enter the market. The mass of users who are already attached to their iPhones and Android devices because of their wide choice of apps are, in a way, the real value of those platforms.

“Take the case of Jolla,” says Constantinou. “In order to start spinning its network effects, it needs to have a critical mass of either users or developers.” He adds, “Microsoft has spent five to ten billion dollars and still hasn’t been able to compete. And that’s two years after they’ve introduced Windows phone. It’s like there’s Coke and Pepsi and everyone else—good luck.”

The comparison of smartphones to soda is an idea invented by Peter Bryer, who spent 16 years in high-level management at Nokia. So what does he think of Jolla? On his blog, he says the company may be the “Red Bull” of this marketplace, a company that could “hit an industry from the side with something different, something fresh, and something unexpected.”

A team of rivals

Jolla’s leadership is well aware of how hard it is to break into a field of entrenched behemoths. One of its solutions is an “interpretation layer” that allows Jolla phones to run most Android apps. But for a lot of people to start using Jolla phones, even in a country like China where many are not yet attached to a particular platform, Sailfish is going to need its own apps, and people to build them, as Constantinou points out.

The company has tried hard to create a culture that will attract such people. Because it’s run by software developers, it espouses values—like sharing, collaboration and transparency—beloved by developers, who it hopes will contribute code for free in their spare time, as typically happens with open-source projects. Android, also open-source, has captured some of that goodwill, but the only company allowed to contribute code to Android is Google itself. Google has also been using heavy-handed tactics to keep Android handset manufacturers in line.

Jolla also comes from a country that is now legendary for its programming prowess. Home of Rovio, maker of Angry Birds, the most-downloaded paid game on iTunes ever, and Supercell, one of the fastest growing game studios ever, Finland is a good place to be popular with programmers. “Finland is a country of five million people and it sure feels like we have five million supporters here,” says Dillon.

Jolla itself has grown from a staff of around 50 in August, expecting to reach 100 by the end of 2012. Many of them will be located in Hong Kong, which will be the headquarters of the Sailfish Alliance.

Open to modification

The alliance symbolizes another key thing that Jolla says will make it different: the company aims to have less control over Sailfish than any other OS maker has over its OS. The purpose of the alliance—which includes Tencent, one of China’s leading online companies, and ST-Ericsson, maker of the chips that already power at least a dozen different Android smartphones—is to make it possible for the various handset makers, software companies and mobile carriers who have a stake in the success of Sailfish to dig into the guts of the OS, make suggestions, tweak it for local markets, and put in new services that can help them generate revenue.

So, for example, if a company like Samsung offers an Android handset, it has to obey by rules laid down by Google so that it can include the Android app store, called Google Play, on its devices. It can’t use another app store. Revenue from Google Play goes to Google, not Samsung. By contrast, if a carrier wants to include, for example, its own app store or music service in Sailfish, that’s no problem.

Dillon says that even though Sailfish will always be open-source, Jolla will make money by licensing the patents the company has on its unusual user interface. He also hints at other, more radical business models that revolve around, for example, making it easier to match users with apps, but he says he can’t yet discuss them. ”I don’t want to go head-to-head with the two big app stores,” says Dillon. “I’d like to do something a bit different.”

Freedom from the patent wars

Jolla’s final advantage is that it believes it can stay out of what has become a massively expensive conflict between phone-makers over intellectual property. Hardly a day goes by that some holder of mobile patents doesn’t initiate a lawsuit against another—the latest is Nokia versus RIM, maker of the Blackberry, and in August a US court awarded Apple $1 billion in damages in its patent infringement suit against Samsung. “There were massive investments from previous customers [Intel and Nokia] to clear MeeGo [now Sailfish] from intellectual property issues,” says Jussi Hurmola, former CEO of Jolla and now a consultant to the company.

This also means that Jolla offers a sweetener to carriers. Because its interface is so different and the OS was written specifically to avoid infringing existing patents, it could be free of the de-facto licensing fees that usually come with using Android on a phone. (As a result, while Google charges nothing for Android, Microsoft is the one that makes money every time an Android-powered handset is sold.)

The Steve moment

“Many people have told us that this is not possible… that the market is flooded,” Jolla VP Pienimäki said at the Sailfish launch. To argue for why the company should succeed he pointed to Jolla’s deal with D.Phone, but also to the research the company has done on Chinese consumers. “We spent hundreds of hours studying the marketplace and consumer behavior in the field, in shops, malls, streets; seeing consumer behavior in the metro, subways, bars. […] That’s the key power of this company—the management is in the field all the time. You can’t outsource this kind of market insight.”

There is a Steve-Jobs-like quality to the pride Dillon and Hurmolla take in their creation and their exacting standards for ease of use. I ask Dillon if he would compare his company to Apple.

“It’s fair enough,” says Dillon. “We inherited some things from MeeGo, and and some of this has evolved into things have become a bit more revolutionary. We’ve really simplified the interaction, and made a lot of things easier to use so they require far less interaction. […] I would like for this to be a major disruption.”

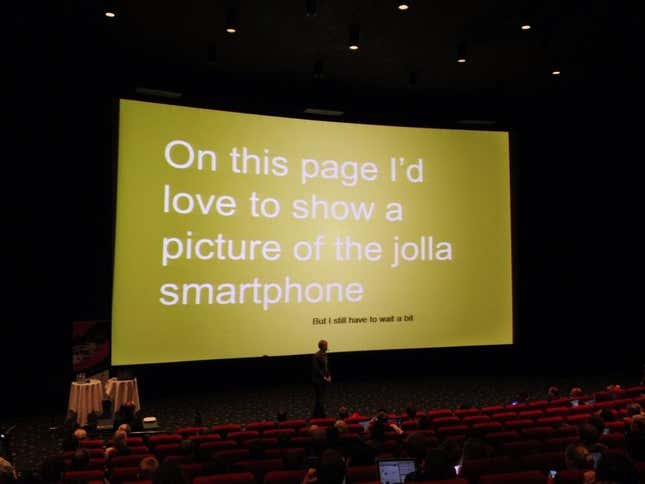

But acting like Steve Jobs and succeeding like Steve Jobs are two very different things. Jolla will unveil its first handsets, and its super-secret alternative business models, around the beginning of 2013, says Dillon, and phones running Jolla should be available by the spring. Even if Jolla ultimately succeeds in China or manages to become the “Red Bull” of the smartphone world, that will be just the beginning of a very long battle.