Two charts that suggest the time is right to dump bonds and buy stocks

Back in July, Bill Gross of bond fund PIMCO proclaimed “the death of equities. He said the average 6.6% annual gain that stocks have posted since 1912 was a “historical freak.” If he had made this announcement back in September 2008, he would have looked like a mystic genius. However, as the Wall Street Journal commented at the time of Gross’ statement, “maybe it’s a buy signal for stocks—go the other way.”

Back in July, Bill Gross of bond fund PIMCO proclaimed “the death of equities. He said the average 6.6% annual gain that stocks have posted since 1912 was a “historical freak.” If he had made this announcement back in September 2008, he would have looked like a mystic genius. However, as the Wall Street Journal commented at the time of Gross’ statement, “maybe it’s a buy signal for stocks—go the other way.”

When a high-profile public figure whose comments can move markets makes an extremely confident generalization, it could be because he feels secure such comments will not offend people. In other words, he knows his words won’t jolt asset prices because almost everyone agrees with him. A market where most participants share an opinion, such as “stocks are bad, which means bonds are good,” is not a great one to buy into. Imagine a housing market in which everyone you know is buying an apartment—or buying six and becoming amateur landlords. Chances are it is going to be difficult to find a bargain.

That is what has been happening with bonds.

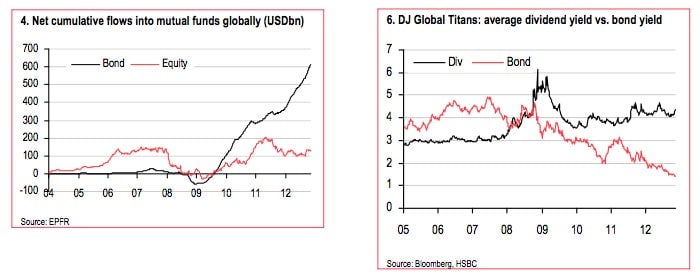

As the chart from HSBC on the left shows, money flows into mutual funds that hold bonds have soared since 2009, while equities have been generally left on the shelf. All this herding into debt securities has made income yields on bonds extremely skinny. Conversely, the chart on the right shows dividend yields on stocks look extremely tempting.

Two oft-quoted investment maxims are “buy low, sell high”—Warren Buffett’s annual investment letters (PDF) are generally a variation on this theme—and “buy when there is blood on the streets,” a comment often attributed to 18th century banking titan Baron Rothschild.

The streets are getting bloodier by the day. The US may be about to fall off the fiscal cliff. The euro zone is in crisis. And the Chinese economy’s apparent recovery may be no more than a case of enthusiastic government life support.

But mutual fund investors are not yet switching into stocks. The issue is fear. Deep, deep fear that companies cannot overcome these scary structural issues. Investors are worried that US companies will post weaker earnings after the cliff dive, while Europe’s biggest and best exporters will lose yet more business from the euro zone. HSBC reckons such anxieties are overblown. In its research note accompanying these charts, the bank forecasts that companies’ earnings will grow 10% in the US next year, 11% in Europe (excluding the UK), and 13% in emerging markets.

The fear is justified. The debate, however, should be whether that fright is priced into shares or whether it has some way to go. Low price-to-earnings ratios are not always a signal to buy equities, as this potted history of bargain basement stock-market disasters, provided by CNN Money, points out.

However, as the Economist wrote recently, stock prices tend to be less about historical events or forecasts about the future of world economies. Instead, they follow a predictable cycle of analysts’ upgrades and downgrades. Fears about the wider economy prompt CEOs and finance directors to look hangdog at investor meetings, which in turn prompts research analysts to downgrade profits forecasts, which lowers stock prices. Then, all of a sudden, the analysts decide enough is enough and proclaim shares are too cheap.

As the Economist explained in its Nov. 22 column:

This is part of a long-established game played in the stock-market. Analysts proclaim that the market is cheap relative to prospective earnings, and advise that investors should pile into shares. As the year progresses, they revise down their forecasts to reflect guidance from corporate executives. Thanks to those downward revisions, companies are able to beat those lower estimates. Analysts can then declare that the stock-market is attractive because profits were ahead of forecasts, and will be even better next year. So the cycle begins again.

FT Alphaville noted that analysts consistently lowered their earnings expectations for Dow Jones stocks in the six months to October. But sentiment is changing. Bloomberg said last month that US stocks were in their “cheapest bull market since Ronald Reagan.” The Wall Street Journal has advised its readers to pile into European shares. Barron’s has even said that some Greek stocks look cheap (paywall) and also tentatively recommended Italian shares (paywall) back in October.

HSBC wrote in its research note, “The momentum of earnings forecasts seems to have turned.”

So we may be reaching that point in the cycle when the analysts sharpen their blue pencils and upgrade forecasts again. That is probably good news for equities. As the Also Sprach Analyst blog points out here, the experts who are entrusted to manage our retirement funds seem to do little else but follow analysts’ recommendations.