Apple is treating the Beats brand remarkably differently than its own

Naming a computer company Apple was a true stoke of genius, the kind that sits beyond the reach of consciousness. With the name came a visual representation. The first, unofficial logo evoked Isaac Newton’s famous epiphany:

Naming a computer company Apple was a true stoke of genius, the kind that sits beyond the reach of consciousness. With the name came a visual representation. The first, unofficial logo evoked Isaac Newton’s famous epiphany:

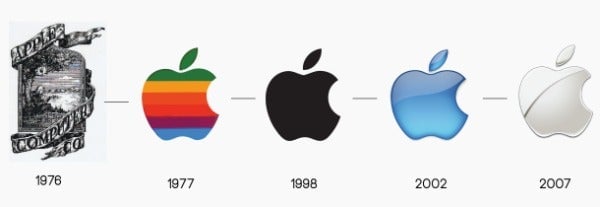

Not a stroke of genius. It was a too kitschy, too busy, and failed to provide an easily memorized and recognized image, a signpost to the company’s products. It was quickly replaced with the simple Apple bite logo that we know today:

Theories of the the logo’s meaning and construction occupy a corner of Apple mythology. Some are misguided (it’s an homage to Alan Turing, it’s a blasphemous reference to the forbidden fruit), while others are playful: A fellow named Barcelos Thiago points out the use of the Fibonacci series in the Apple logo (and in just about everything else).

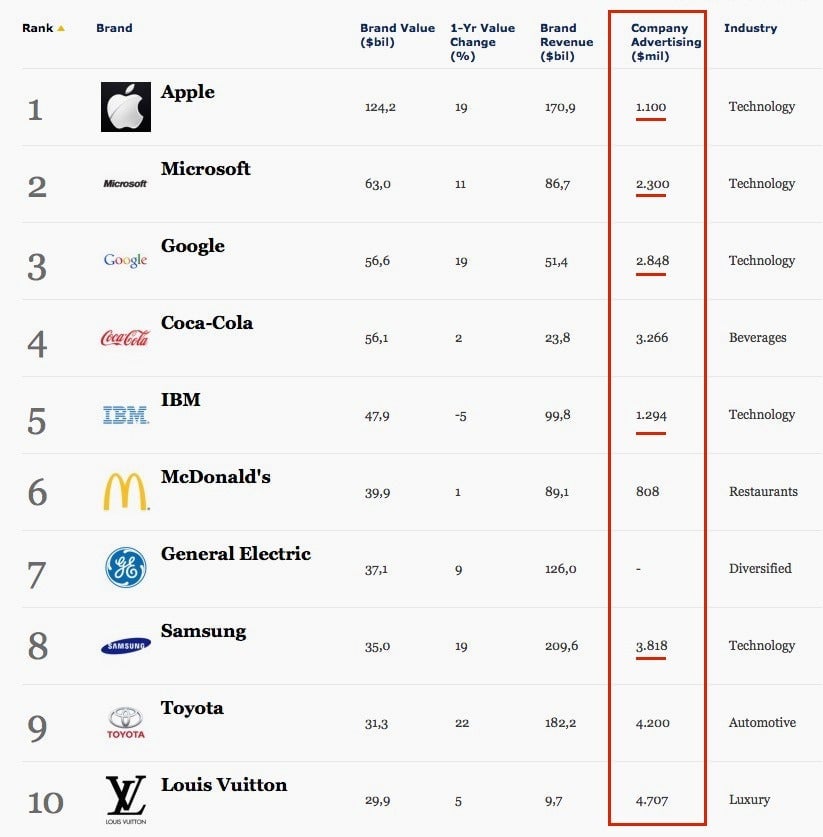

Apple’s reputation, products, and imagery have coalesced into a brand, a mark that’s burned (as in the word’s origin) into the collective consciousness. Last year, Forbes called Apple the world’s most valuable brand. It’s impossible to measure contribution of the name and logo to the company’s success, but a peek at the Forbes’ list shows how little Apple spends advertising its products compared to Microsoft, Google, Samsung, or less technical companies such as Cocoa-Cola or Louis Vuitton:

A brand exists in a circular relationship with the promises that it makes to the customer. If the products and services deliver on the pledge, the customer is more inclined to swear loyalty to the brand. A close examination of some of these circles brings up apparent paradoxes. Burberry’s, for example, was once credited for inventing the oxymoronic “mass-marketing of exclusivity”—a trick that Louis Vuitton now performs at the highest of levels, a feat that requires an advertising budget more than four times Apple’s.

The late Fred Hoar, an erudite Harvard graduate who once served as the head of Apple’s marketing communications, likened brand advertising to urinating inside one’s dark-blue flannel suit: It makes you feel warm but no one sees anything.

No such waste at at Apple. The product, not the brand, is the hero. Apple’s ads focus on the product, on what it does, on the feats that it allows unnamed customers to perform. The brand ascends to where it belongs, above specific products and promotions.

Apple ads are also (mostly) free from celebrity endorsements

The imprimatur of a noted figure can be effective—I’m thinking of George Clooney’s second banana persona in Nestlé’s tongue-in-cheek Nespresso ads. But we usually feel the use of endorsements as an admission that the product needs stilts—that it lacks differentiation.

If Apple ever hires a spokesperson for its iPhones, even if it’s Andrew Wiles or, in a couple of years, a happily retired Barack Obama, you should look elsewhere: The brand has started to unravel. (Apple does, of course, occasionally use celebrities—this ad featuring the Williams sisters for example—but as Adweek points out, it’s rare.)

Given this thinking, what do we make of Apple’s other brand, Beats?

Beats was acquired last year, for $3.2 billion. The reasons behind the price are still a bit unclear, but we already see ads that aren’t much more than mini-movies of celebrity athletes (Colin Kaepernick, Cesc Fabregas, LeBron James) shutting out the noise of irate fans and implications of social injustice by donning the company’s headphones.

Does the Beats line needs stilts in order to achieve differentiation and justify its high pricetag? The quality of Beats headphones is a contested subject. One study shows they’re preferred by teens, other painstaking reviews claim there are many better headphones. On this, because of my old ears, I don’t have much of an opinion beyond my post “Sound Holiday Thoughts“ written in December 2013.

It’s a novel situation: Apple “thinks different” about the two brands it now owns. The personal-computing brand is carefully nurtured, pruned, protected—now at the pinnacle. The other is just as carefully kept apart.

Walk into an Apple store and you’ll see Beats headphones and speakers next to Bose, B&O, and Logitech products. Before the acquisition, this was no surprise, Beats products were just third-party accessories. Now, they’re Apple products, even if they don’t carry the Apple logo. They sit on the shelves next to their competitors, such as the $999.95 Denon Music Maniac Artisan headphones. Can you imagine the Apple Store selling Surface Pro hybrids, stocking them right next to the iPads?

You won’t find Apple logos on Beats headphones, and you won’t find any Apple references in a Beats headphone commercial. The headphones are part of the Beats Music streaming music ecosystem whose goal is to play everywhere, including the Windows Phone Store.

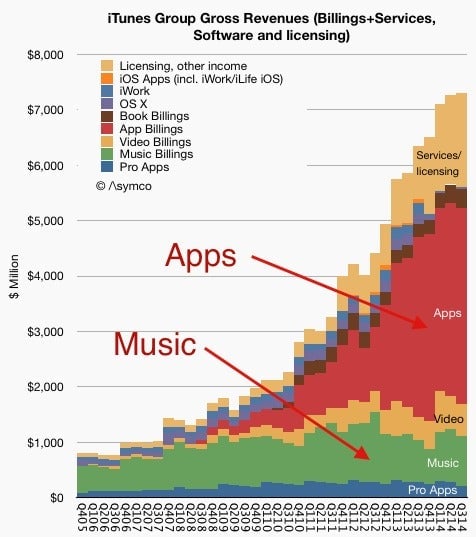

But there’s a problem. As Horace Dediu notes, Apple’s music business has stopped growing, vastly overwhelmed by apps:

The Beats acquisition raised many questions still unanswered: Why get into the headphones and loudspeakers business? What is the Job To Be Done here? Same queries for the Beats Music streaming service, one that might benefit from its bundling with Apple hardware, but whose curation “sounds” less than enthralling thus far, notwithstanding CEO Tim Cook’s enthusiasm.

As the year unfolds, we’ll see how Beats products and services grow the brand—and if its isolation from the Apple brand is merely prophylactic caution—or part of a bigger plan to stay on top of the music world.

The Apple Watch won’t be the only development to…watch this year.

You can read more of Monday Note’s coverage of technology and media here.