This Morgan Stanley bond trader is the most interesting man left on Wall Street

Wall Street banks have never liked talking about their top traders and the bets they make. And since the financial crisis hit—when big bets on products such as mortgage bonds went massively wrong and the financial system nearly collapsed—the traders have faded even further into the background.

Wall Street banks have never liked talking about their top traders and the bets they make. And since the financial crisis hit—when big bets on products such as mortgage bonds went massively wrong and the financial system nearly collapsed—the traders have faded even further into the background.

In fact, many of the most daring have left the world of banking, now under the intense gaze of regulators, for the more freewheeling world of hedge funds.

But there are still a few big traders on Wall Street. And as head of Morgan Stanley’s interest rates business, which covers sales and trading of government bonds such as US Treasuries and related products, Glenn Hadden is one of the biggest.

While he strives to maintain a low profile, Hadden found himself in the news Monday as word emerged that he is being investigated in connection with trades he conducted in 2008, when he used to work for Morgan Stanley’s arch-rival Goldman Sachs. The Journal reports:

Mr. Hadden, who has been credited with reviving part of Morgan Stanley’s bond-trading operation, was notified in recent months that he was being investigated for certain “Treasury futures orders” placed in December 2008, while he was working at Goldman, according to an updated report from the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority. Finra tracks enforcement actions against brokers and many Wall Street traders.

Mr. Hadden is one of the highest paid professionals at Morgan Stanley and has been known throughout his career for aggressive and profitable risk taking. It is unusual for someone of Mr. Hadden’s stature to be the target of a civil complaint like this, and if he is found to have violated exchange rules, he could, in the extreme, face millions in fines and be barred from trading on the CME Group.

While Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs learned about the investigation only in recent months, both firms were aware of another controversy involving Mr. Hadden that took place not long after the CME trading now under scrutiny.

After receiving complaints involving Mr. Hadden from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Goldman Sachs took the extraordinary step of putting him on paid leave in 2009, according to several people briefed on the matter.

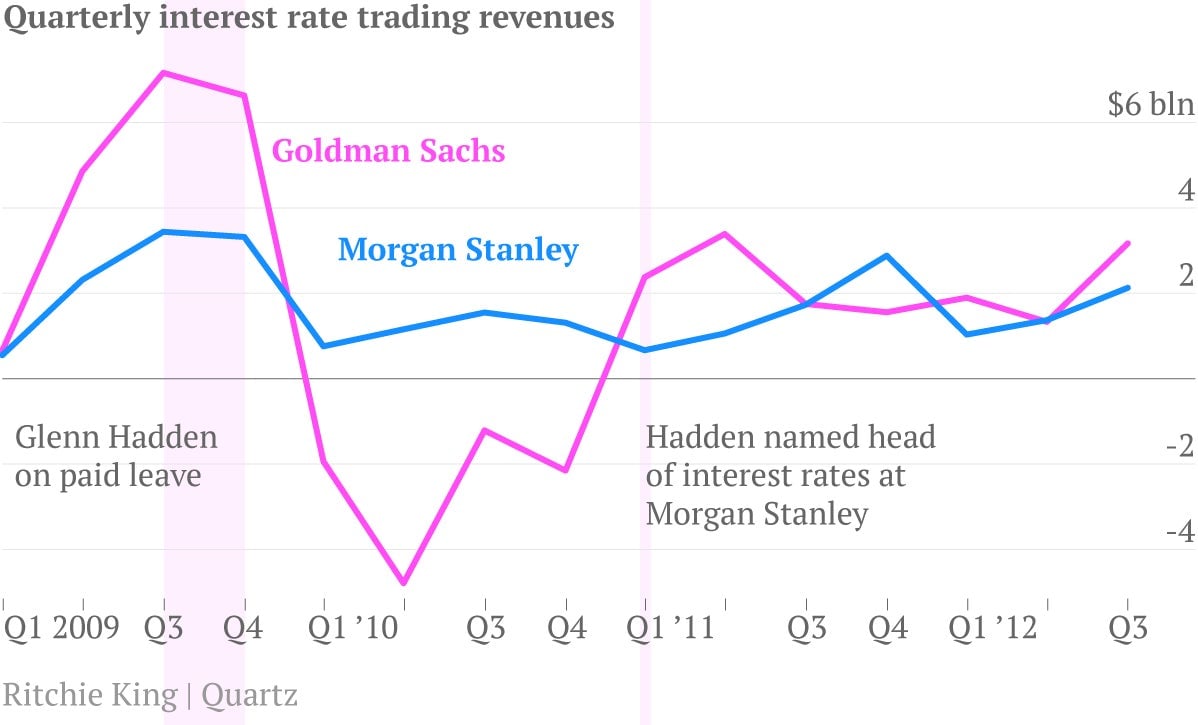

What’s particularly striking is how sharply revenues tied to interest rates trading at Goldman Sachs tumbled after Hadden was put on paid leave.

Here’s s look at the interest rate trading revenues from quarterly bank holding company data reported to the Federal Reserve. In 2009, Goldman’s interest rates desk was churning out massive profits. So, Hadden’s disappearance from day-to-day operations at Goldman prompted a lot of head-scratching from clients at the time.

Check out how sharply Goldman’s truly interest rate trading revenues reverse after Hadden goes on paid leave. And when he pops up at Morgan Stanley, their revenues start ratcheting higher, even overtaking Goldman at moments. Clearly, the guy knows how to make money.

But aren’t the days of swashbuckling bets on Wall Street supposed to be behind us? After all, wasn’t that what the whole deal with the Volcker Rule was supposed to be about? You remember the Volcker Rule, don’t you? That’s the provision of the Dodd-Frank financial overhaul that would prohibit bank traders from making risky bets with the bank’s own capital: so-called proprietary trading. Proprietary trading is an area where banks made massive profits in the run-up to the crisis.

But there are two things to remember. The first is that the Volcker Rule doesn’t really exist yet. The five regulatory agencies that are involved in drafting the final Volcker Rule say a final version should be complete before the end of the year. And the second thing: US Treasury bonds—the largest and most important market for interest rate traders—would be exempt from the rule. That would seem to incentivize banks to move whatever bet-making they still do to their interest-rates trading desks.