Russia can’t figure out how to fix its ailing economy

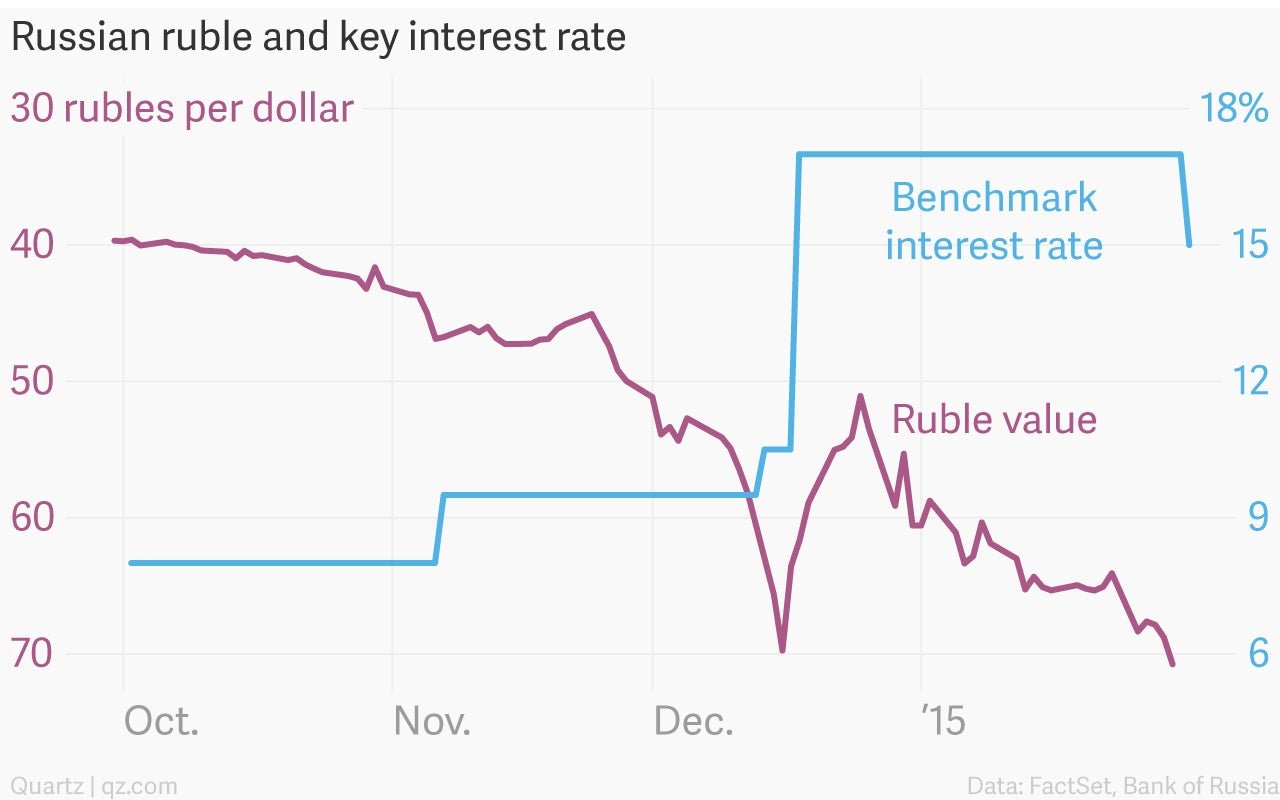

The ruble has been sliding and inflation is running in the double digits. If Russia’s central bank was going to do anything at its regularly scheduled meeting today, analysts figured it might consider hiking interest rates further. After all, the last time the ruble sank to around 70 to the dollar, last month, the bank jacked up its key rate, in the middle of the night, from 10.5% to 17%.

The ruble has been sliding and inflation is running in the double digits. If Russia’s central bank was going to do anything at its regularly scheduled meeting today, analysts figured it might consider hiking interest rates further. After all, the last time the ruble sank to around 70 to the dollar, last month, the bank jacked up its key rate, in the middle of the night, from 10.5% to 17%.

The Russian central bank has not lost its capacity to surprise. It cut its benchmark rate today, to 15%. Almost nobody saw that coming. The ruble sank against the dollar, testing levels last seen during the December rout:

There are two ways to read today’s surprise decision. The first is to go by what the central bank itself says—boosting economic growth is now more important than fighting inflation or supporting the ruble. The rate cut is aimed at “averting the sizeable decline in economic activity,” the bank said in a statement. Russian GDP grew by just 0.6% last year, according to the bank’s estimates, and will fall by more than 3% in the first half of this year. This “subdued aggregate demand,” as the bank puts it, will keep inflation in check, with price growth eventually dropping below 10% a year from now.

The second interpretation is that the bank succumbed to political pressure to loosen policy. Its drastic hike last month bought the ruble little respite, but generated a lot of angst among Russia’s political, banking, and corporate establishments, who would all rather see lower rates.

A recent reshuffle of top staff at the central bank was read by many as the government exerting more control over the ostensibly independent institution. This won’t help the credibility of central bank governor Elvira Nabiullina, who until today was seen as an inflation hawk—indeed, this was the bank’s first rate cut since she took over in 2013.

Whatever the case, what is clear is that Russia is scrambling to come up with the best policy mix to address the toxic combination of stagflation, low oil prices, capital flight, sanctions, and a host of other ills infecting the country’s sickly economy. Rates are hiked and then they’re cut. Inflation rises and GDP falls. The ruble swings up and down (but mostly down).

These days, there’s only one Russian indicator that has been relatively steady—president Vladimir Putin’s approval rating has been locked at 80 to 85% for nearly a year. One gets the impression that volatility elsewhere will be tolerated, as long as this remains the case.