As a famous Russian once asked, what is to be done?

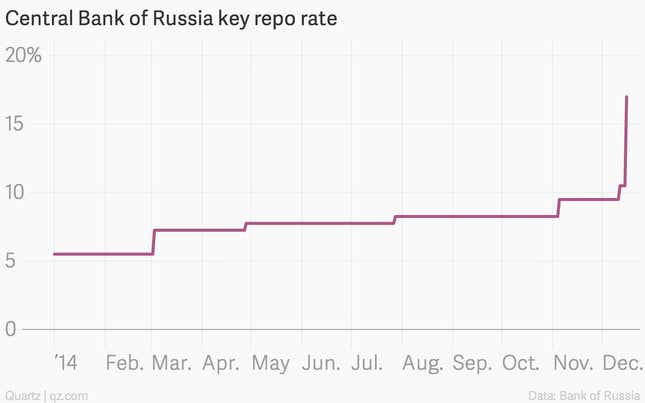

The Central Bank of Russia just answered with a monster interest rate hike. The central bank increased its benchmark interest rate from 10.5% to 17% in a surprise announcement at roughly 1am Moscow time on Dec. 16. The move is meant to stabilize the country’s cratering currency. (The ruble was down a spectacular 11% today.)

One way to think about central bank interest rates is as the interest you would get for holding that central bank’s currency. So higher interest rates make it more attractive, all else equal, to hold that currency. That, in theory, discourages people from selling it, which is what has been pushing down the price.

Will it work? No one knows. But the immediate reaction of the market—albeit in the thinly traded overnight session—was to halt the ruble’s seemingly relentless slide. On the other hand, the sharp increase in interest rates is likely to serve as a serious headwind to Russia’s already declining economy.

In short, Russia is caught in a vise. The value of the commodity on which it relies, crude oil, is collapsing, and along with it the ruble. The weak ruble is driving inflation up sharply. Economic growth is crumbling. And doubts are growing about the ability of Russia’s heavily indebted energy firms to roll over their debt next year. (They are locked out of global capital markets by international sanctions, inspired by Russia’s fun-and-games with neighbor Ukraine earlier this year.)

What else could go wrong? Well, the banks could go wrong. As of yet, there’s been very little sign that faith in the Russian banking system is ebbing away. But that would likely change if the currency continues to collapse at the rate it’s going; it’s down roughly 50% so far this year. Typically, a currency decline like this at some point spurs depositors to pull their cash out of banks and try to find some sort of asset to put it in. Such a bank run would only exacerbate the economic woes of the country.

Fundamentally, Putin’s Russia is facing the biggest set of economic challenges it has yet encountered. The combination of a slumping economy and rising inflation makes it likely that Russians will see their real incomes fall uncomfortably next year. Vladimir Putin’s approval rating, which has fluctuated between 80% and 90% since the start of Russia’s meddling in Ukraine, could suffer, since apart from belligerent foreign adventures, the other thing that his popularity has historically depended on is rising standards of living for the population.

But in all likelihood, it will take much more economic disruption to dislodge Putin. Russians have seen far, far worse. Between 1989 and the late 1990s, the economic output of the former Soviet Union declined by a nearly unimaginable 40%, resulting in terrible destruction to personal incomes. Putin rose to power out of that chaos, in which widespread gangsterism and economic collapse made life deeply unpleasant. Compared to that, the current economic stress is merely a passing squall.