Google is key to our getting more personalized, trustworthy news

Last year Richard Gingras and Sally Lehrman came up with the Trust Project (full text here, on Medium.) Gingras is a seasoned journalist and the head of news and social at Google; Lehrman is a senior journalism scholar at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University in California.

Last year Richard Gingras and Sally Lehrman came up with the Trust Project (full text here, on Medium.) Gingras is a seasoned journalist and the head of news and social at Google; Lehrman is a senior journalism scholar at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University in California.

Their starting point is readers’ eroding confidence in media. Year after year, every survey confirms the trend. A recent one, released at the Davos Economic Forum by the global PR firm Edelman confirms the picture. For the first time, according to the 2014 version of Edelman’s Trust Barometer, public trust in search engines surpasses trust in media organizations (64% vs 62%.) The gap is even wider for Millennials who trust search engines by 72% vs. 62% for old media.

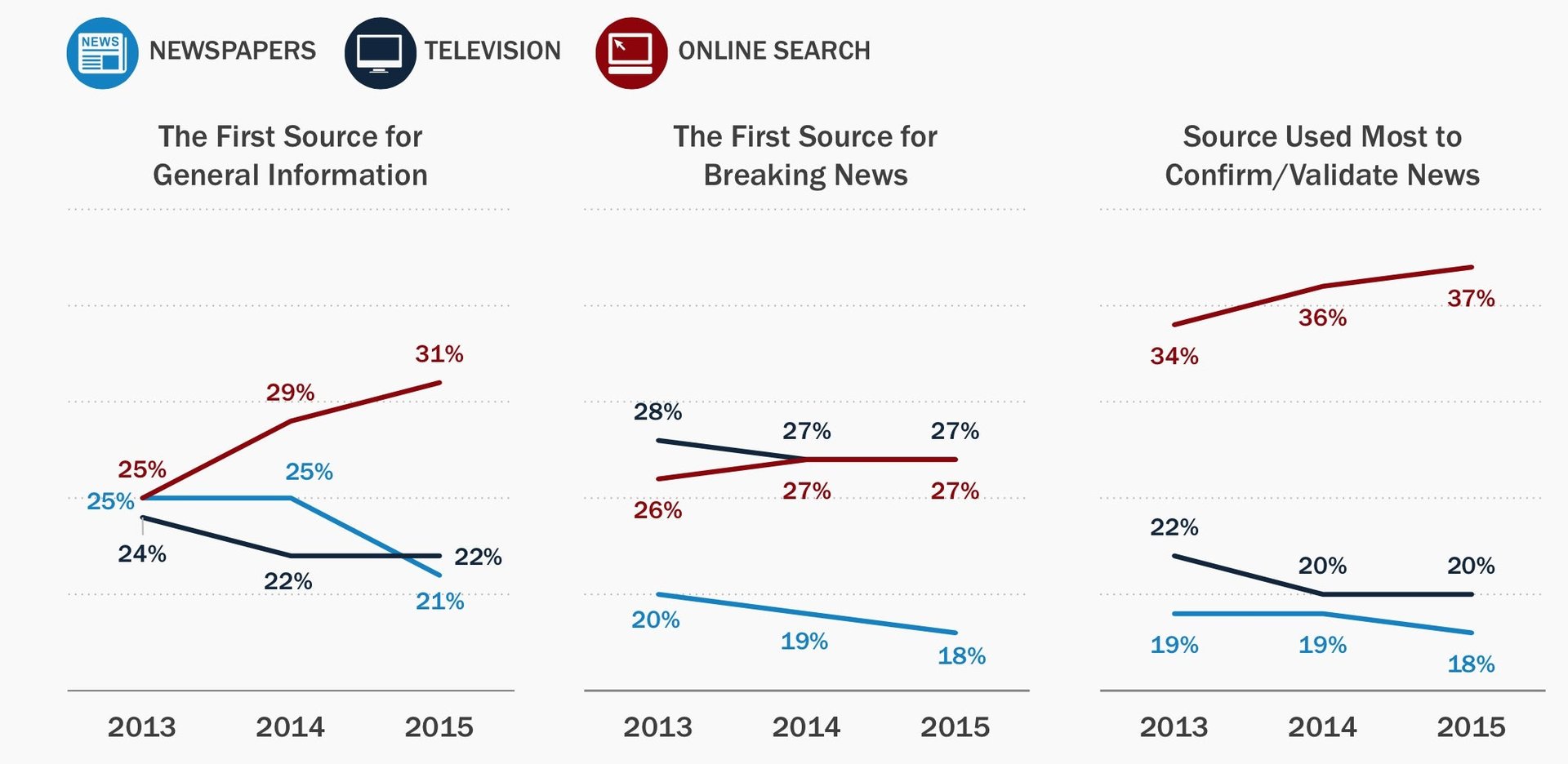

And when it comes to segmenting sources by type—general information, breaking, validation—search leaves traditional media even further in the dust.

No wonder why, during the recent terrorist attack in Paris, many publishers saw more than 50% of their traffic coming from Google. This was reflected on with a mixture of satisfaction (our stuff surfaces better in Google search and Google News) and concern (a growing part of news media traffic is now in the hands of huge US-based gatekeepers.)

Needless to say, this puts a lots of pressure on Google (unlike Facebook, which is not so concerned with its growing role as a large news conduit). Hence the implicit mission given to Gingras and others to build on this notion of trust.

His project is built around five elements to parse news content with:

1. A mission and ethics statement

As described in The Trust Project:

One simple first step is a posted mission statement and ethics policy that convey the mission of a news organization and the tenets underlying its journalistic craft. Only 50% of the top 10 US newspapers have ethics policies available on the web and only 30% of 10 prominent digital sites have done so.

The gap between legacy and digital native news media is an interesting one. While the former have built their audience on the (highly debatable) notion of objective reporting and balanced points of view, digital natives come with a credibility deficit. Many of the latter are seen as too close to the industry they cover—some prominent ones did not even bother to conceal their ties to the venture capital ecosystem—others count among their backers visible tech industry figures. Others are built around clever click-bait mechanisms that are supplemented—marginally—by solid journalism. (I’ll let our readers put names on each kind.)

In short, a clear statement on what a media source is about—and what their potential conflicts of interests are—is a mandatory building block for trust.

2. Expertise and disclosure

Here is the main idea:

Far too often the journalist responsible for the work is not known to us. Just a byline. Yet expertise is an important element of trust. Where has their work appeared? How long have they worked with this outlet? Can audiences access their body of work?

Nothing much to add. Each time I spot an unknown and worth-reading writer, my first reaction is to Google him/her to understand who I’m dealing with. Encapsulating background information in an accessible way (and standardized enough to be retrievable by a search engine) makes plain sense.

3. Editing disclosure, i.e. details on the whole vetting process a story had gone through before hitting the pixels

Fine, but it’s a legacy media approach. Stories by Benedict Evans, Horace Dediu, or Jeff Jarvis (see his view on the Trust Project), just to name a few respected analysts, are not likely to be reviewed by editors—but their views deserve to be surfaced as original content. Therefore, editing disclosure should not carry a large weight in the equation.

4. Citation and corrections

The idea is to have Wikipedia-like standards that give access to citations and references behind the author’s assertions. This is certainly an efficient way to prevent plagiarism, or even “unattributed inspiration.” The same goes for corrections and amplifications, as the digital medium encourages article versioning.

5. Methodology

What’s behind a story? How many first-hand interviews and reporting done on location is there as opposed to the soft reprocessing of somebody else’s work? Let’s be honest, the vast majority of news shoveled on the internet won’t pass that test.

Google’s idea to weigh all of the above is supposed to create a standardized set of “signals” that will extract quality stuff from the vast background noise on the web, in objective ways. Not an easy task.

In fact, Google News already works that way. In a Monday Note based on Google News’ official patent filing (see: “Google News: The Secret Sauce“), I looked at the indicators identified by Google to improve its news algorithm. There are 13 of them, ranging from the size of the organization’s staff to the writing style. It certainly worked fine (otherwise, Google News wouldn’t be such a success). But it is no longer enough. Legacy media are now in a constant race to produce more in order to satisfy Google’s insatiable appetite for fresh fodder. In the meantime, news staffs keep shrinking and “digital serfs,” hired for their productivity rather than their journalistic acumen become legion. Also, criteria such as the size of a news staff no longer matter as much, this because independent writers and analysts—as those mentioned above—have become powerful and credible voices.

In addition, any system aimed at promoting quality and value is prone to being abused. Search algorithms have become a moving target for all the smart people the industry has bred, forcing Google to make several thousand adjustments to its search formulae every year.

The News Profile and Semantic Footprint approach

If the list stated by the creators of the Trust Project is a great start, it has to be supplemented by other systems. Weirdly enough, profiling techniques used in digital advertising can be used as a blueprint.

Companies specializing in audience profiling are accumulating anonymous profiles in staggering numbers—to name just one, in Europe, Paris-based Weborama has collected 210 million profiles (40% of the European internet population), each containing detailed demographics and consumer tastes for clothing, gadgets, furniture, transportation, navigation habits, etc. Such data are sold to advertisers who can then pinpoint who is in the process of acquiring a car, or looking for a specific travel destination. No one ever opted-in to give such information, but we all did by allowing massive cookie injections in our browsers.

In that case, why not build a “News Profile?” It could have all the components of my news diet: The publications I subscribe to, the media I visit on a frequent basis, the authors I search for, my average length of preferred stories, the documentaries I watch on YouTube, the decks I download from SlideShare… Why not add the books I ordered on Amazon, and the people I follow on Twitter, etc.? All of the above already exists inside my computer—in the form of hundreds, if not thousands, of cookies collected while I navigated the web.

It could work this way: I connect—this time knowingly—to a system able to reconcile my “News Profile” to the “Semantic Footprint” of publications, and also to authors (regardless of their affiliation, from the New York Times’ John Markoff to Andreessen Horowitz’s Ben Horowitz), type of production, etc. Such profiling would be fed by criteria described in the Trust Project and by Google News algorithm signals. Today, only Google is in the position to perform such a daunting task: It has done part of the job since the first beta of Google News in 2002—it collects thousands of sources, and it has a holistic view of the Internet. I personally have no problem with allowing Google to create my News Profile based on data it already has about me.

I can hear the choir of whiners from here. But, again, it could be done on a voluntary basis. And think about the benefits: A skimmed version of Google News, tailored to my preferences, that could include a dose of serendipity for good measure… isn’t it better than a painstakingly assembled RSS feed that needs constant manual updates? To me it’s a no-brainer.

You can read more of Monday Note’s coverage of technology and media here.