Corrupt Chinese officials who have fled to Australia remain out of Beijing’s reach

Chinese officials recently trumpeted the return of an “economic fugitive” from Italy as a precedent-setting moment in the country’s long battle to snare corrupt officials and other white collar criminals who have fled overseas with ill-gotten gains.

Chinese officials recently trumpeted the return of an “economic fugitive” from Italy as a precedent-setting moment in the country’s long battle to snare corrupt officials and other white collar criminals who have fled overseas with ill-gotten gains.

“This extradition case will serve as a demonstration for other western countries,” a Ministry of Public Security official promised. But many foreign governments are still reluctant to cooperate with Beijing’s global manhunt: see Australia as Exhibit A.

The Australian government under prime minister John Howard signed an extradition treaty with China in 2007, which excluded “political offenses” and any instance when the person sought could face the death penalty and gave the Chinese government the right to seize any property in Australia that the wanted individual has acquired. (The death penalty exclusion is particularly relevant now—China just executed a former mining tycoon accused of corruption who said tearfully during his trial that he had been framed.)

But the Australian legislature never enacted legislation to implement the treaty, which is required before it can take effect, and the pact’s status is now the subject of some dispute.

Australian foreign minister Julie Bishop told reporters in November that “Australia doesn’t have an extradition treaty with China and that present money laundering laws were adequate for dealing with the problem,” the Australian newspaper reported.

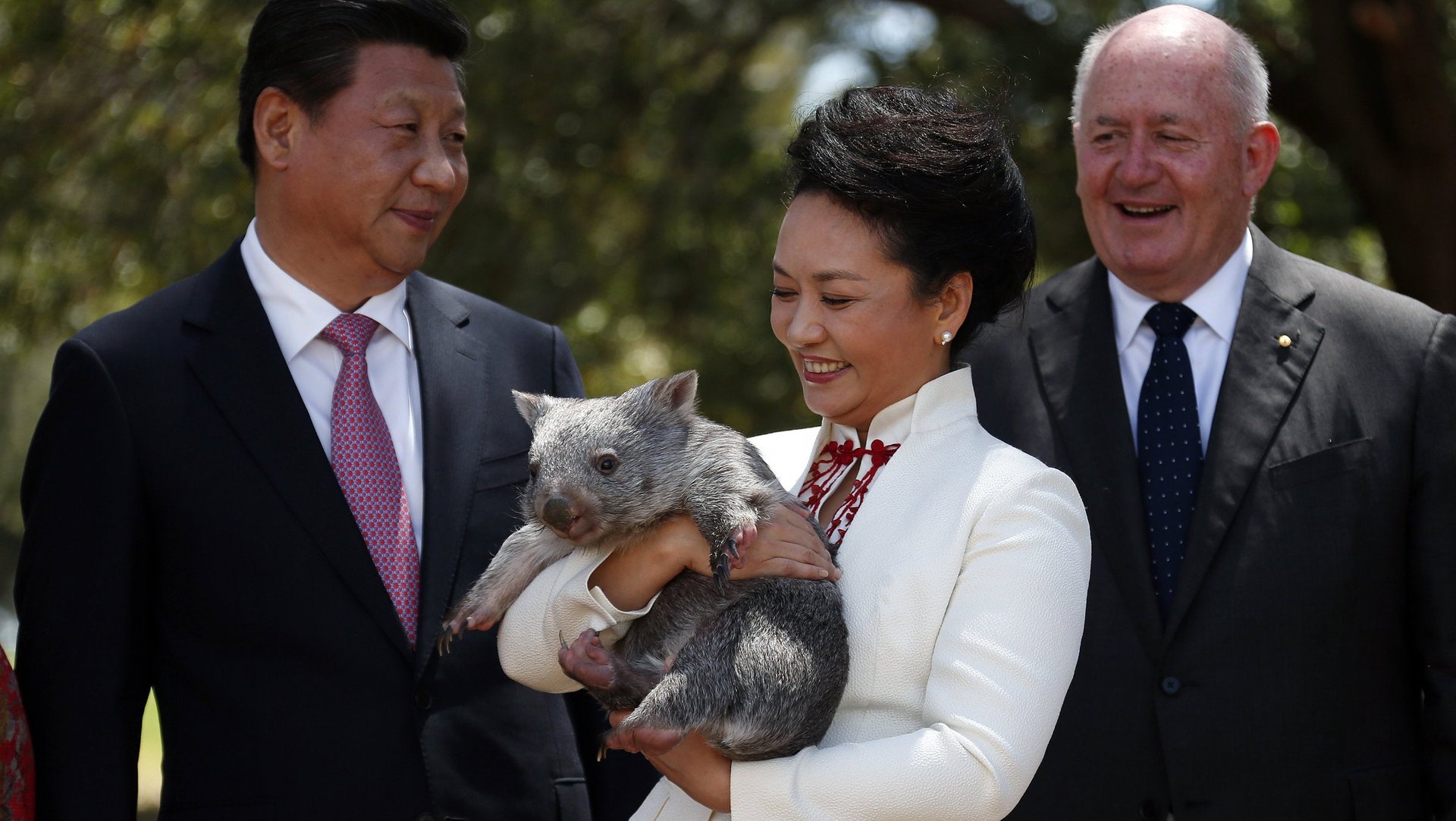

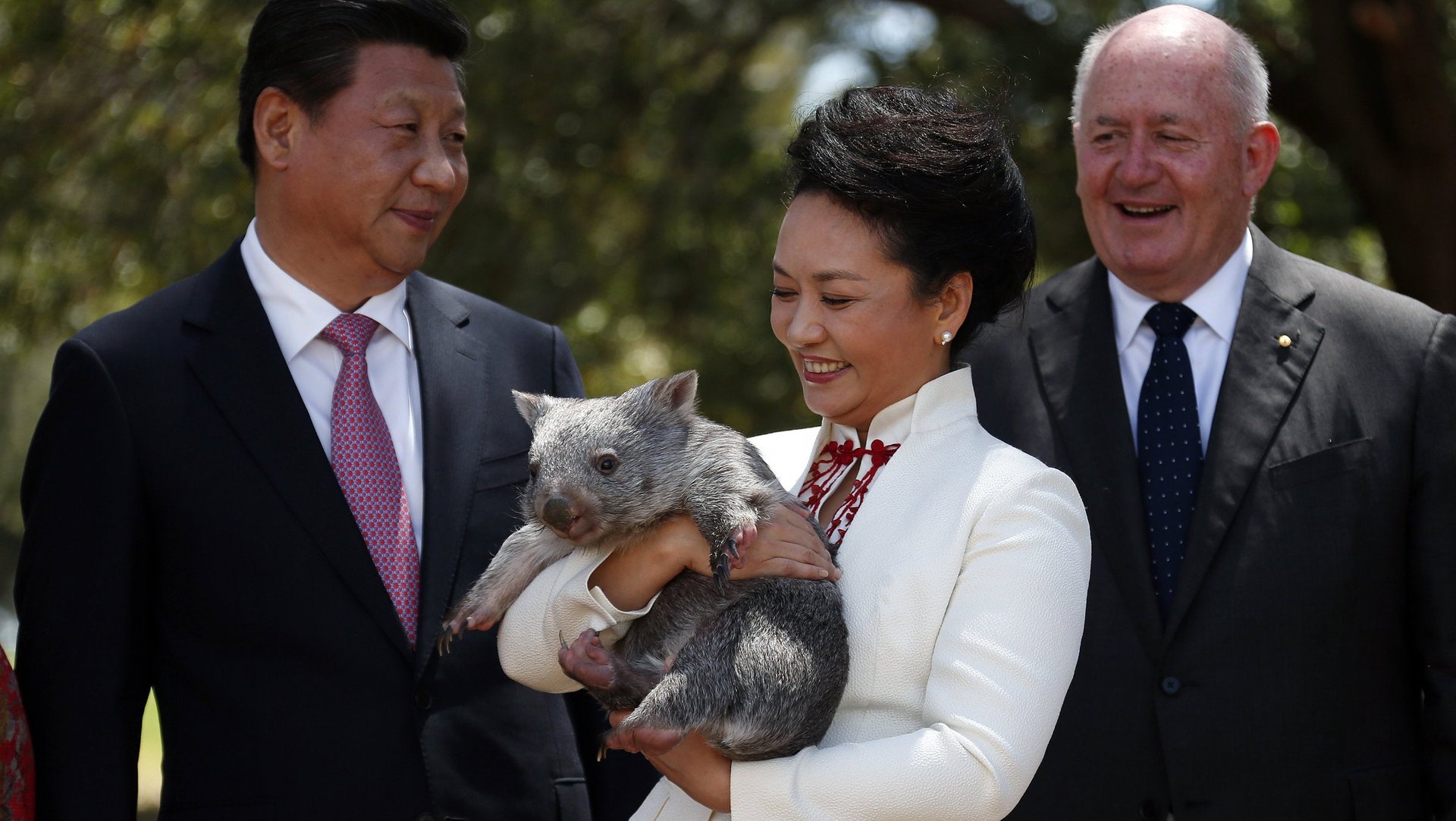

Shortly after that comment was made, Chinese president Xi Jinping visited Australia. According to an official in China’s foreign ministry, officials discussed the unratified treaty during the trip and “Australia pledged to speed up the approval,” Xinhua reported.

A spokesperson for the Australian attorney general’s office told Quartz that, despite Bishop’s statement, the implementation of the 2007 extradition treaty is still “subject to ongoing consideration.” Australia can still consider extradition requests from China based on several multilateral treaties both countries have signed, like the UN Convention Against Corruption and the UN Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime. But the spokesperson declined to say whether China had successfully made any such requests.

With prime minister Tony Abbott struggling to fend off a leadership challenge, the odds are that the ratification of a politically contentious treaty with China is not likely to happen any time soon.

Getting other countries to agree to extradite Chinese citizens accused of economic crimes is a key part of an ongoing push to seize assets acquired overseas by corrupt officials and businessmen, and return the money to China. China’s wealthy have moved billions of dollars out of the country in recent years, sinking it into real estate from Vancouver to Sydney, as well as art, wine and other assets, often while obtaining visas to live overseas. The US, Australia and Canada are the most popular destinations for Chinese fugitives—and perhaps not coincidentally, none of the three have an extradition treaty currently in force.