Foreign cash, red flags: The case for making US realtors report suspicious activity

A wave of billions of dollars in foreign money, some of it fleeing tax authorities, unfriendly political regimes and anti-corruption investigations at home, has flowed into US real estate in recent years, leaving the country dotted with high-end homes owned by often-absentee landlords.

A wave of billions of dollars in foreign money, some of it fleeing tax authorities, unfriendly political regimes and anti-corruption investigations at home, has flowed into US real estate in recent years, leaving the country dotted with high-end homes owned by often-absentee landlords.

Over a dozen foreign nationals who own multimillion-dollar condos in Manhattan’s Time Warner building have been the subject of government investigations overseas, the New York Times reports. New York magazine dubbed the city’s real estate “the new Swiss bank account” last year, after an ICIJ investigation found “corrupt politicians, tax dodgers and money launderers around the globe” were buying properties. In Miami, Russian and Chinese buyers are fueling another boom in luxury condo construction, just six years after the industry’s historic crash there.

When eyeing other liquid, high-ticket assets in the US, like bonds or public shares, foreign purchasers come under a lot more scrutiny from regulators and market makers, but investing in the property market allows them to be nearly anonymous.

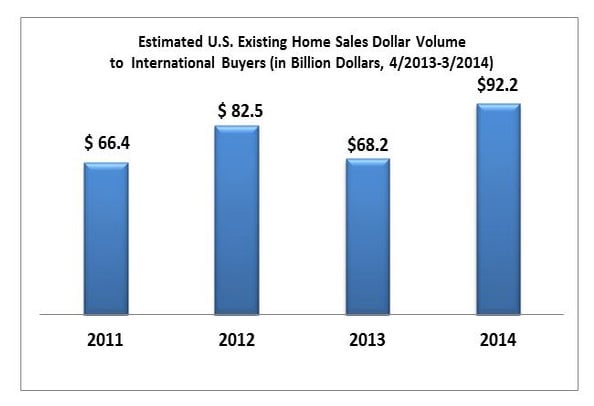

Foreign buyers bought $92 billion in US residential real estate in the 12 months ended April 1, 2014, the National Association of Realtors reports, much of it probably completely legal. But regular checks on buyers that used to surround real estate transactions in the United States, when property was typically purchased with a mortgage, have completely fallen by the wayside in recent years.

Instead, as many as 70% of properties bought by international buyers are now paid for in cash, the realtor group reports, up from 33% in 2007. The buyer may come with a check or another cash equivalent that a seller puts into a bank as legitimate proceeds of a home sale. While banks are required to file a Suspicious Activity Report, or SAR, with the US Treasury if they suspect a client is depositing or transferring corrupt money, real estate agents and the lawyers who work on these deals have no such requirements. The real estate commission model means agents are paid to sell, and often get higher percentages of subsequent sales the more properties they move, so there’s no incentive to flag suspicious deals.

US authorities taxed with keeping the proceeds of corruption and graft out of the US say SAR reports are a “huge help” to law enforcement, and “requiring a broader range of players,” like real estate agents, to file them would keep more corrupt money out of the US, as one assistant US attorney told the Nation.

In 2012, the NAR issued a list of guidelines for when realtors should voluntarily file an SAR to alert the government to a potential money-laundering transaction. For example, they flag transactions that have a large geographic distance between the buyer and the property, involve a shell corporation in the deal, “use large amounts of cash,” or involve a buyer who “brings actual cash to the closing.” All of these red flags are present in many recent New York City real estate transactions, recent reports suggest, but realtors rarely file SARs.

Stepping up regulation of the real estate industry, and realtors’ facilitation of dodgy transactions, is a cause that’s been doggedly made by some investors and especially former Michigan senator Carl Levin, but it never gained much traction.

That’s in part because real estate agents have a highly-organized and influential lobbying group, with the ear of many in the US Congress. The National Association of Realtors (NAR), at 1.1 million-strong, is the largest professional organization in the world, and was the eighth-largest political action committee in the US in the last election cycle, contributing to 400 senators and congressmen.