The only story on Swedish monetary policy you ever have to read

Sweden’s Riksbank joined the central banking bizarro world today, pushing its key benchmark interest rate into negative territory. In other words, instead of paying interest to institutions that park money with it, Sweden’s central bank—like the national banks of Switzerland and Denmark and the European Central Bank—is now charging a small fee to safeguard the cash.

Sweden’s Riksbank joined the central banking bizarro world today, pushing its key benchmark interest rate into negative territory. In other words, instead of paying interest to institutions that park money with it, Sweden’s central bank—like the national banks of Switzerland and Denmark and the European Central Bank—is now charging a small fee to safeguard the cash.

The turnabout reflects one of the world’s most important macroeconomic trends of the moment: Lowflation.

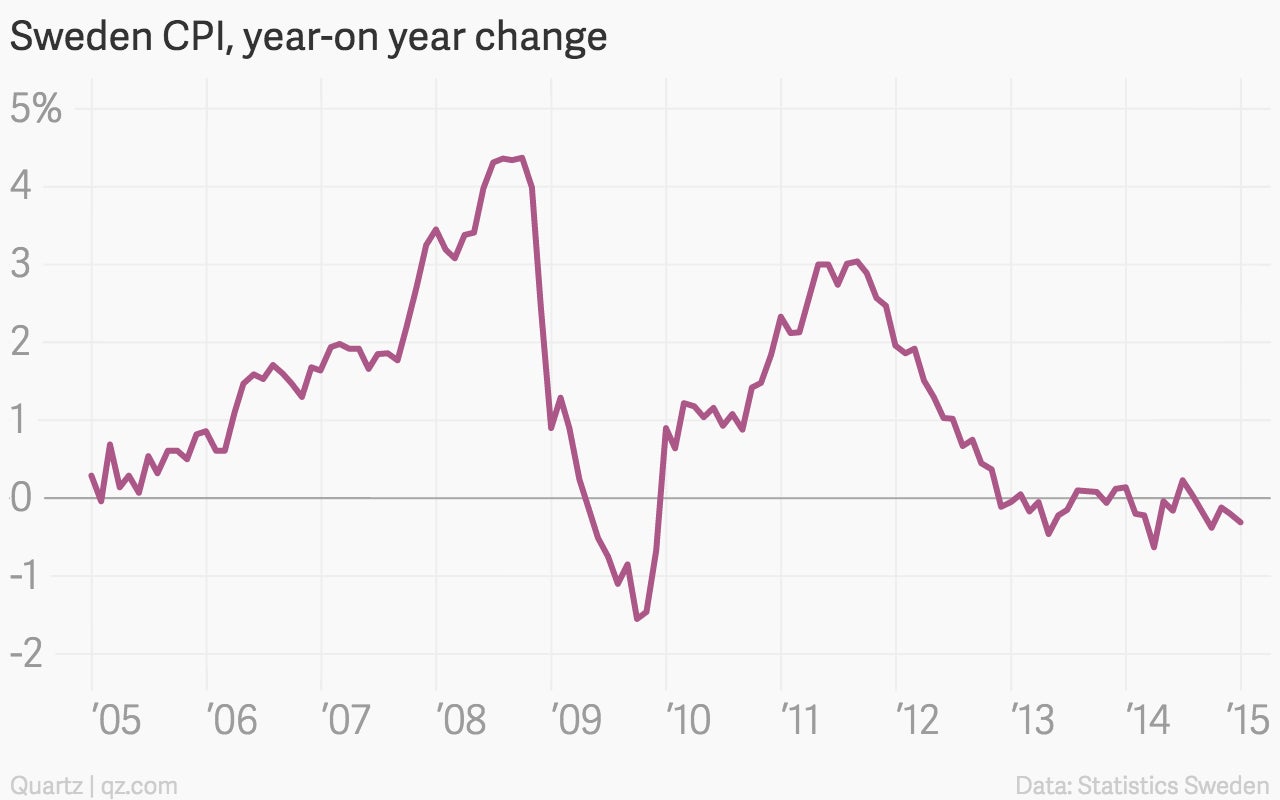

Countries around the world are seeing a sharp slowdown in price growth. In fact, much of Europe is in outright deflation right now, including Sweden if you go by its headline national consumer price index. (Its core inflation index, which strips out seasonal noise as well as the impact of food and energy prices, isn’t in negative territory, but is quite low.)

While falling prices might sound good to consumers, they’re actually very bad for an economy as a whole. If households become accustomed to falling prices, it prompts them to put off purchases. (Why buy now, if it will be cheaper tomorrow?) For any individual shopper this strategy might make sense. But when it happens en masse it acts as a tremendous headwind to growth. Worst of all, once deflation takes hold, it can be very difficult to get out of.

That’s why the Riksbank is now pulling out all the stops to try to generate rising prices. Negative interest rates are is supposed to penalize saving and prompt people to spend and invest instead. The Riksbank is creating new money electronically and using it to buy government bonds, in an effort to push more money into the economy and weaken the currency, which is another attempt to elbow institutions and consumers to spend rather than save.

Of course, it’s worth pointing out that it was central bankers who actually got Europe into this mess, by failing to fully understand the depths and risks of the economic and employment crisis born out of the European debt mess. The ECB was slow to recognize that it has to start printing money to keep Europe from being sucked into a deflationary vortex. And Swedish policy makers made a massive mistake by embarking on a series of interest rate hikes in 2010, despite the fact that unemployment was too high, and core inflation was too low.