The life expectancy of more than half of India’s population could increase by 3.2 years if the country can meet its air quality standards, according to a new study by economists and public policy experts at the universities of Chicago, Yale and Harvard.

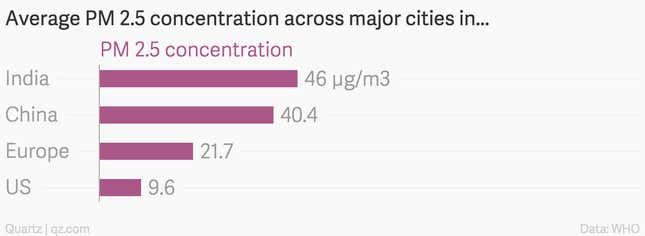

About 54.5% of India’s population currently lives in areas where levels of PM 2.5 in the air are way higher than what is considered safe. PM 2.5 are tiny and dangerous airborne particles, less than 2.5 microns in size, and fine enough to enter deep into the lungs and the bloodstream.

Exposure to such toxic air is reducing the lifespan of these 660 million Indians by over three years. In other words, the country stands to lose 2.1 billion life-years if it does not take concrete steps to curb air pollution, the study noted.

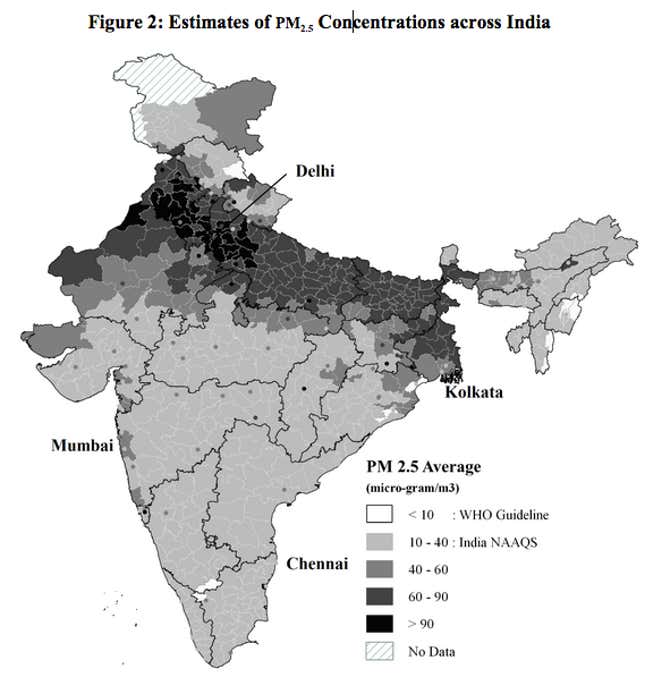

The authors of the study gathered data on the levels of PM 2.5 across India from the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) and used satellite-based estimates where CPCB’s data was unavailable.

However, the study says that the actual cost of pollution in India could be even higher than just the adverse impact on its citizen’s life span:

The loss of more than two billion life years is a substantial price to pay for air pollution. And yet this may still be an underestimate of the costs of air pollution, because we do not account for the impact of other air pollutants, the impacts of particulates on morbidity or labour productivity, as well as preventive health or avoidance costs borne by Indian households.

Most polluted capital

India is home to 13 of the 20 most polluted cities in the world. It also has the highest rate of deaths caused by chronic respiratory diseases. In fact, the World Health Organisation (WHO) found New Delhi, the country’s capital, to be the most polluted city in the world, although the government disagrees.

The above map shows that the people living in northern India are breathing in a much more toxic air compared to most other parts of the country. But the effects of air pollution vary with the social and economic background of people.

For example, a traffic policeman, who spends much of his day out on the road, faces a greater exposure to high pollution levels as opposed to a person staying at home, the researchers note.

The study also points out that there hasn’t been any change in India’s air quality in the last five years. But then nobody really knows about the severity of India’s air pollution as most states use dodgy equipment and methods, which often produce inaccurate data.

India must improve the accuracy of pollution data and has to set up more monitoring stations, the study suggests, alongside restructured environmental regulations and an emission trading system.