Low oil prices are hitting the UK where it hurts: the North Sea

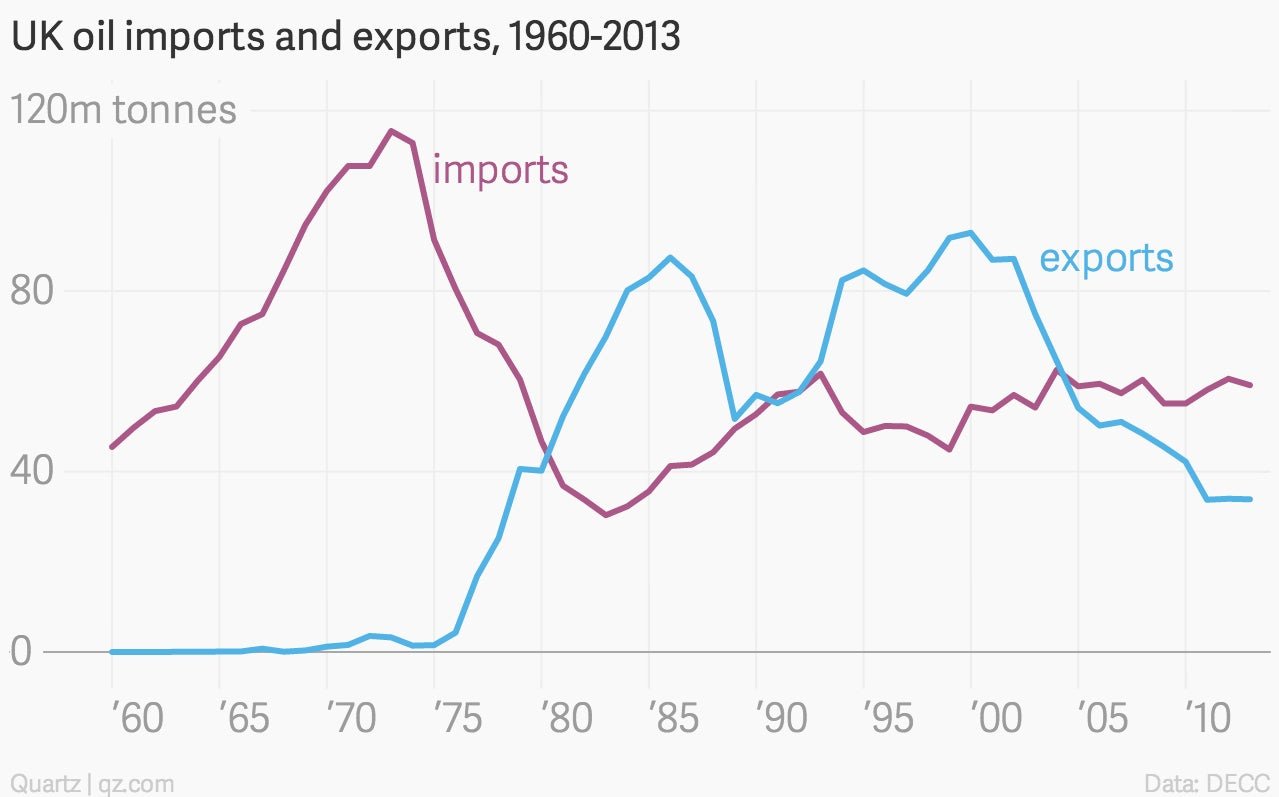

The UK’s North Sea oil story can be told in one line: a steep climb, a dip, a jolt to a new peak, and a long, steady decline. The area of sea that filled government coffers through the 1980s and 1990s, and gave rise to the Brent benchmark, is thoroughly past its heyday.

The UK’s North Sea oil story can be told in one line: a steep climb, a dip, a jolt to a new peak, and a long, steady decline. The area of sea that filled government coffers through the 1980s and 1990s, and gave rise to the Brent benchmark, is thoroughly past its heyday.

Supplies are no longer as plentiful, and what remains is harder to extract. That means spending more to produce less—the North Sea attracted £14.4 billion of investment of in 2013, the highest for 30 years, according to industry body Oil and Gas UK.

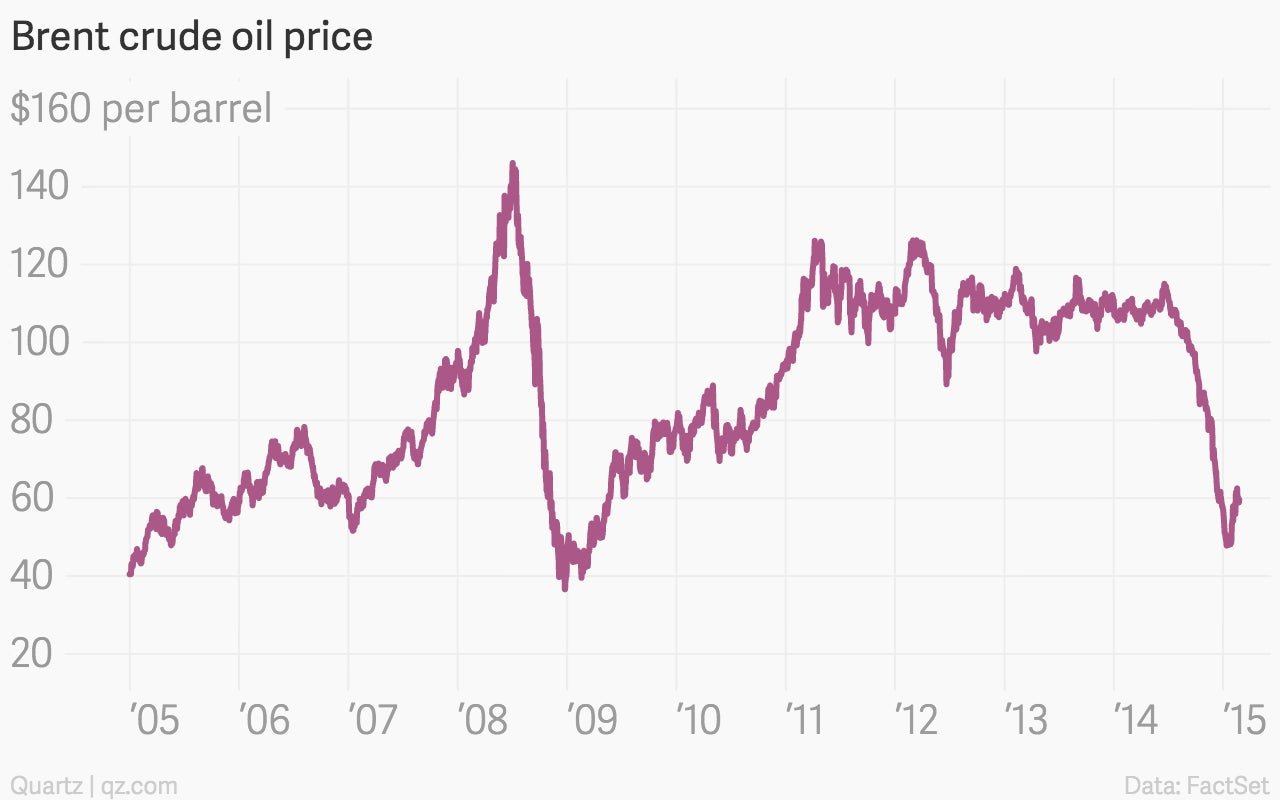

But then, the oil price began to fall.

The confluence of the structural decline and the fall in prices has hit the extraction industry hard, with employers changing their shift patterns (paywall) and cutting pay. This, in turn, has prompted the threat of strikes. It’s already a tough business, and one that’s failing to attract enough people. In a December 2014 survey, over 70% of companies working in the North Sea reported that they were experiencing a skills shortage (pdf, p.23), with the problem particularly acute in Aberdeen, the north-Scotland hub of the offshore oil industry.

The same survey predicted a 9% fall in overall employment on the UK continental shelf from 375,000 today to 340,000 in 2019, or 35,000 jobs lost in five years. That won’t give the striking workers much leverage.

The response from companies to falling prices has been to staunch the flow of money into unprofitable ocean. BG Group and Shell have made cuts. BP said it would slash capital expenditure by 20% in 2015. The chief executive compared the slump to 1986, telling the Telegraph that low oil prices would be good for the UK economy but “difficult in Aberdeen.” The difference between 1986 and 2015 is that few expect a grand resurgence in production when prices begin to rise.

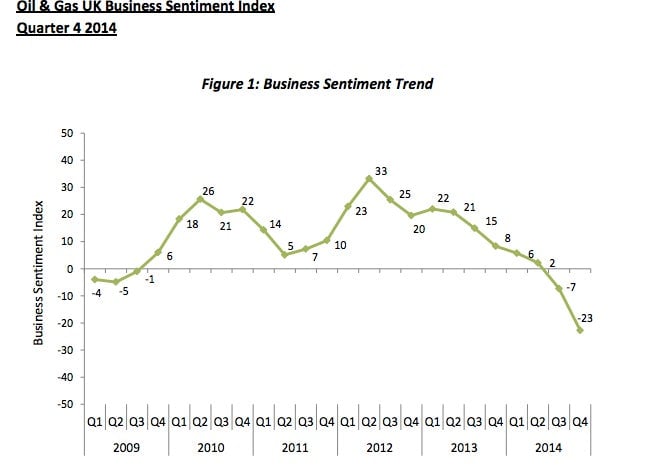

In short, North Sea drillers are down in the dumps (pdf):

Meanwhile, the UK remains thirsty for oil. Imports overtook exports for what’s probably the final time in 2005. Imports also rose above production in 2011.

As North Sea fields run dry, this may give impetus to new projects seeking to use infrastructure in the area for renewable energy generation instead. That could help save jobs, at least for workers who can tailor offshore expertise for wind instead of oil. But it will be of little comfort to oil companies.