China’s consumer economy is a long way off, despite rising wages

China’s government has long had an ambition to rebalance the economy away from an over-reliance on state investment and export-led growth, and towards domestic consumption. Doing so is widely seen as the only way to prevent a prolonged slowdown in GDP growth. But where the incomes that will fuel that consumption are concerned, China is in a bad place.

China’s government has long had an ambition to rebalance the economy away from an over-reliance on state investment and export-led growth, and towards domestic consumption. Doing so is widely seen as the only way to prevent a prolonged slowdown in GDP growth. But where the incomes that will fuel that consumption are concerned, China is in a bad place.

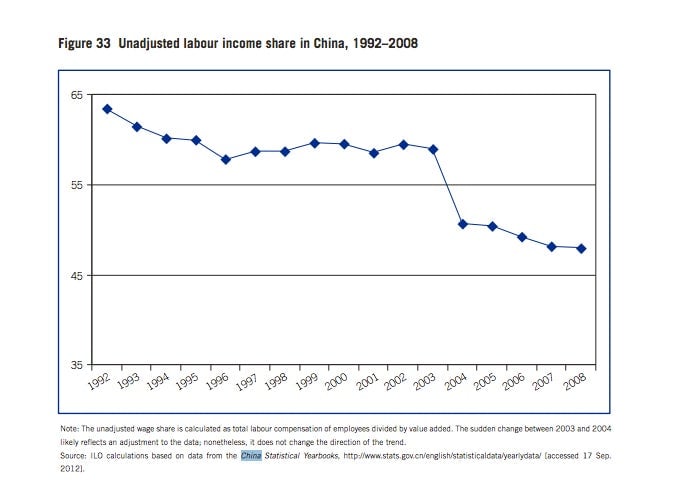

The UN’s latest annual report on global wages, just issued, shows that even though labor costs in the country have tripled over the last decade (pdf, p.xiv), prompting manufacturers to shift to Southeast Asia or in some cases replace human workers with robots, wages are shrinking as a proportion of GDP, and have been for two decades.

The data show a flip-side to China’s economic boom. From about 2003, when the country’s growth engine really revved up, the people got left behind. Even though manufacturing wages are rising fast in China’s wealthy southeast—and thus lifting the national average—the country is not creating enough middle-class jobs to usher in a consumer economy.

Now, these figures are worth taking with a small pinch of salt. Wages take time to catch up to a period of fast growth, and true consumption may be higher than it seems because people under-report their spending. Also, China is not the only place where wages are falling as a share of GDP. In the US it has been happening for decades.

But America does not face China’s rebalancing challenge. Domestic consumption is already a strong driver of the US economy. Americans spend a lot of their wages. The Chinese save around 30% of their disposable income (pdf, p.1). The comparable figure in the US is 3.4%. Household consumption is 34% of GDP in China, compared to around 71% in the US.

Instead of tackling wages as a share of growth, the Beijing government could also introduce a social safety net. The Chinese are so thrifty because they have to deal with a total lack of welfare and social housing. Anyone born since 1979, when China implemented its one-child policy, has to save up to support his or her parents and two sets of grandparents alone.

Another reason China has to get people spending more—via higher wages or by means of introducing welfare—is that so much state investment is dangerous. Building big projects takes a lot of bank lending. That could usher in a debt crisis similar to that of Japan in the 1990s. And often, China’s stimulus projects are uncommercial. The country has been investing heavily in new aluminum smelters that seem completely unnecessary amid a global supply glut of the metal.

But while economists have warned that too much of China’s growth comes from state investment and exports for several years, turning this around will be such a huge job that China could suffer very low growth rates for years. So the country remains hooked on economic stimulus.

The beneficiaries of state stimulus spending tend to be big companies also owned by the government. As Lombard Street Research Hong Kong-based economist Freya Beamish puts its: “our main problem with the Chinese model at the moment is that the corporate state get too much of the pie. Too little goes to households.”

China’s private enterprises are the engines of wealth creation (pdf p.16). But they usually miss out on government contracts and have lower access to bank credit.

Meanwhile, because they enjoy monopoly positions and easy access to credit, China’s state owned enterprises (SOEs) can be badly run businesses that hobble on unprofitably for decades. If these failing firms were allowed to die—they tend to be kept on life support to avoid mass unemployment (paywall)—they could end up being replaced with better, more innovative companies that pay higher wages.

But despite the lip service they pay to rebalancing, China’s leaders may resist economic reforms that make SOEs lose out. Most of the country’s incoming top leadership are so-called “princelings”, meaning their families are powerful Communist dynasties. It is often observed that the princelings’ families derive much of their wealth from government backed companies. Solving that problem will take a while.