After 50 years, Warren Buffett is suddenly shifting his target metric

The pursuit of value has been the abiding obsession of Warren Buffett in the 50 years since he took over Berkshire Hathaway and, in fact, far before then.

The pursuit of value has been the abiding obsession of Warren Buffett in the 50 years since he took over Berkshire Hathaway and, in fact, far before then.

But he’s been upfront about the fact that value is quite a hazy concept. He’s never actually stated what he thinks the real value is of Berkshire Hathaway, the conglomerate he built by fusing an insurance empire to a struggling textile company in the 1960s. Precision, he’s said repeatedly, just isn’t possible.

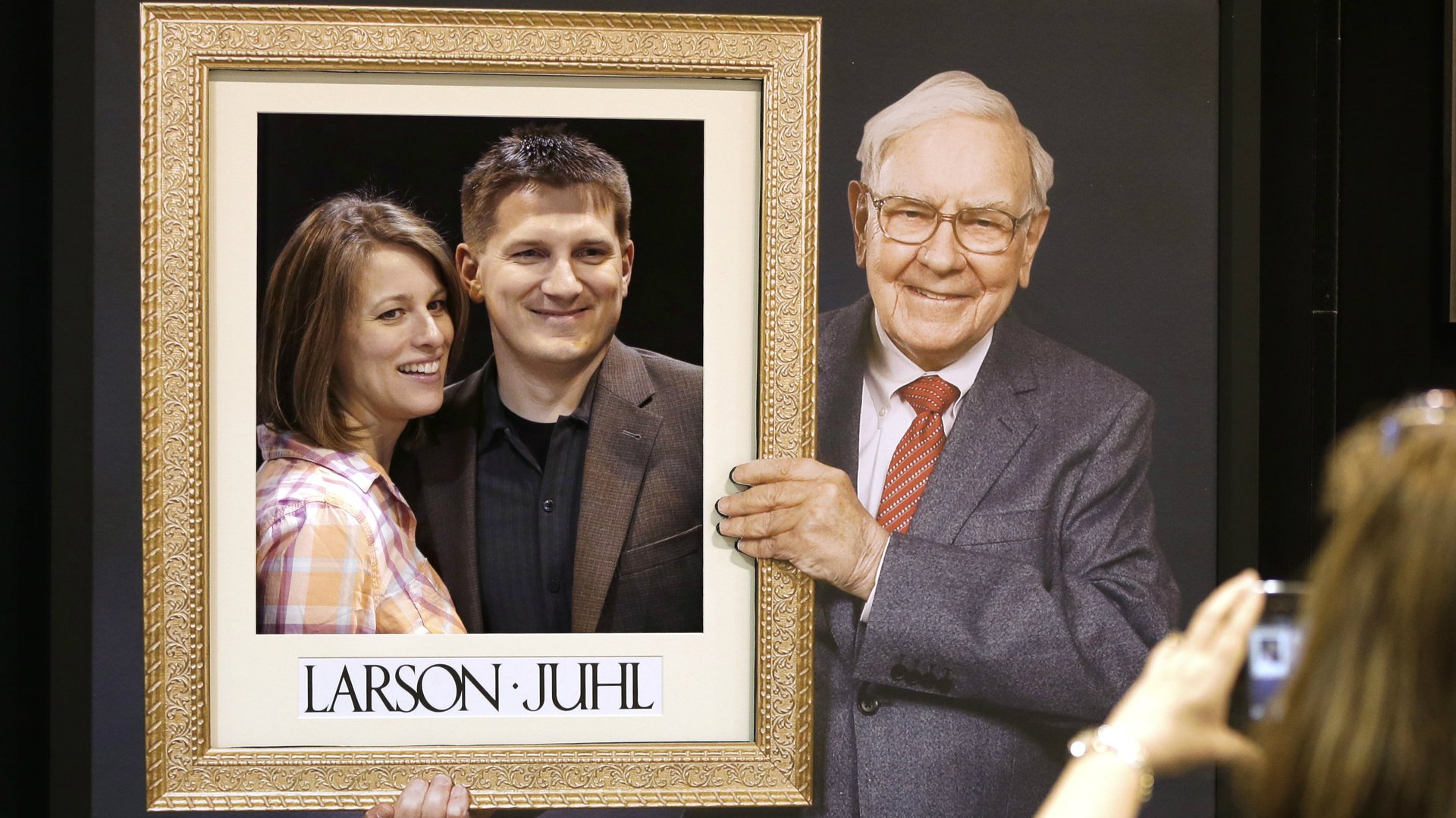

Still, for five decades he’s used a simple metric as an imprecise proxy for the intrinsic value of the company: Book value per-share. In recent years, the first page of Buffett’s hotly awaited letter to shareholders has been a plain vanilla comparison of the year-on-year change in Berkshire Hathaway’s book value per-share (essentially the value of the company after paying off all its debts), and the performance of the S&P 500 index, including dividends.

That is until today, when the latest edition sported a third column of comparison featuring market-value—total shares outstanding, multiplied by market prices. Here’s how Buffett justifies the shift:

During our tenure, we have consistently compared the yearly performance of the S&P 500 to the change in Berkshire’s per-share book value. We’ve done that because book value has been a crude, but useful, tracking device for the number that really counts: intrinsic business value.

In our early decades, the relationship between book value and intrinsic value was much closer than it is now. That was true because Berkshire’s assets were then largely securities whose values were continuously restated to reflect their current market prices. In Wall Street parlance, most of the assets involved in the calculation of book value were “marked to market.”

Today, our emphasis has shifted in a major way to owning and operating large businesses. Many of these are worth far more than their cost-based carrying value. But that amount is never revalued upward no matter how much the value of these companies has increased. Consequently, the gap between Berkshire’s intrinsic value and its book value has materially widened.

Translation: Buffett’s saying the intrinsic value of the business (which he measures by estimates of discounted cash flows), is a lot higher than book values, which are driven by historical cost (that is the price Buffett has paid for the businesses he bolted onto the conglomerate). That’s undoubtedly true.

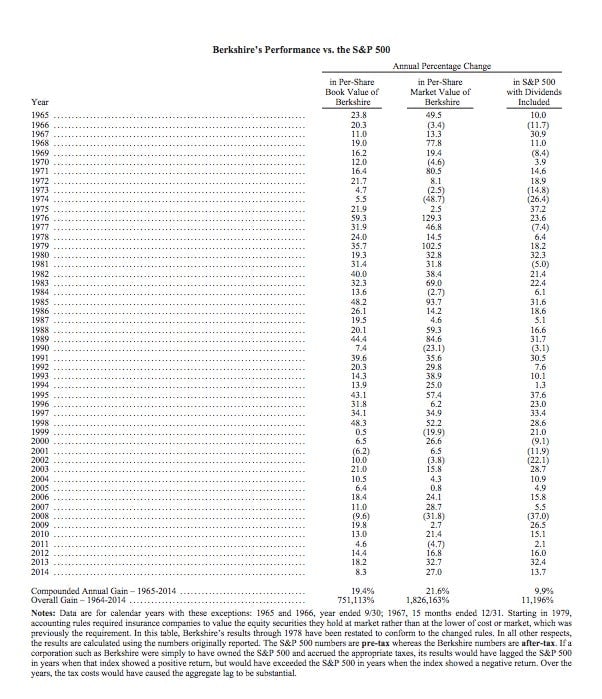

But you can’t help but note that the introduction of a new performance benchmark comes just as Buffett’s been consistently underperforming on his traditional bogey. Growth in Berkshire’s book value per-share has trailed the S&P’s performance in four of the last five years. It was up 8.3% in 2014, compared to the S&P’s return of 13.7%.

Using Berkshire’s new guidelines however, market value per-share was up a far more robust 27%, outshining the S&P.