Mobile operators want to do away with online passwords

Nobody likes passwords. They’re hard to remember, we’re terrible at coming up with good ones, and they’re not much use anyway. Yet they refuse to go away. The closest we’ve come to getting rid of them is by using the likes of Google and Facebook to log in to other websites. At least that reduces the number of passwords and login details we have to manage.

Nobody likes passwords. They’re hard to remember, we’re terrible at coming up with good ones, and they’re not much use anyway. Yet they refuse to go away. The closest we’ve come to getting rid of them is by using the likes of Google and Facebook to log in to other websites. At least that reduces the number of passwords and login details we have to manage.

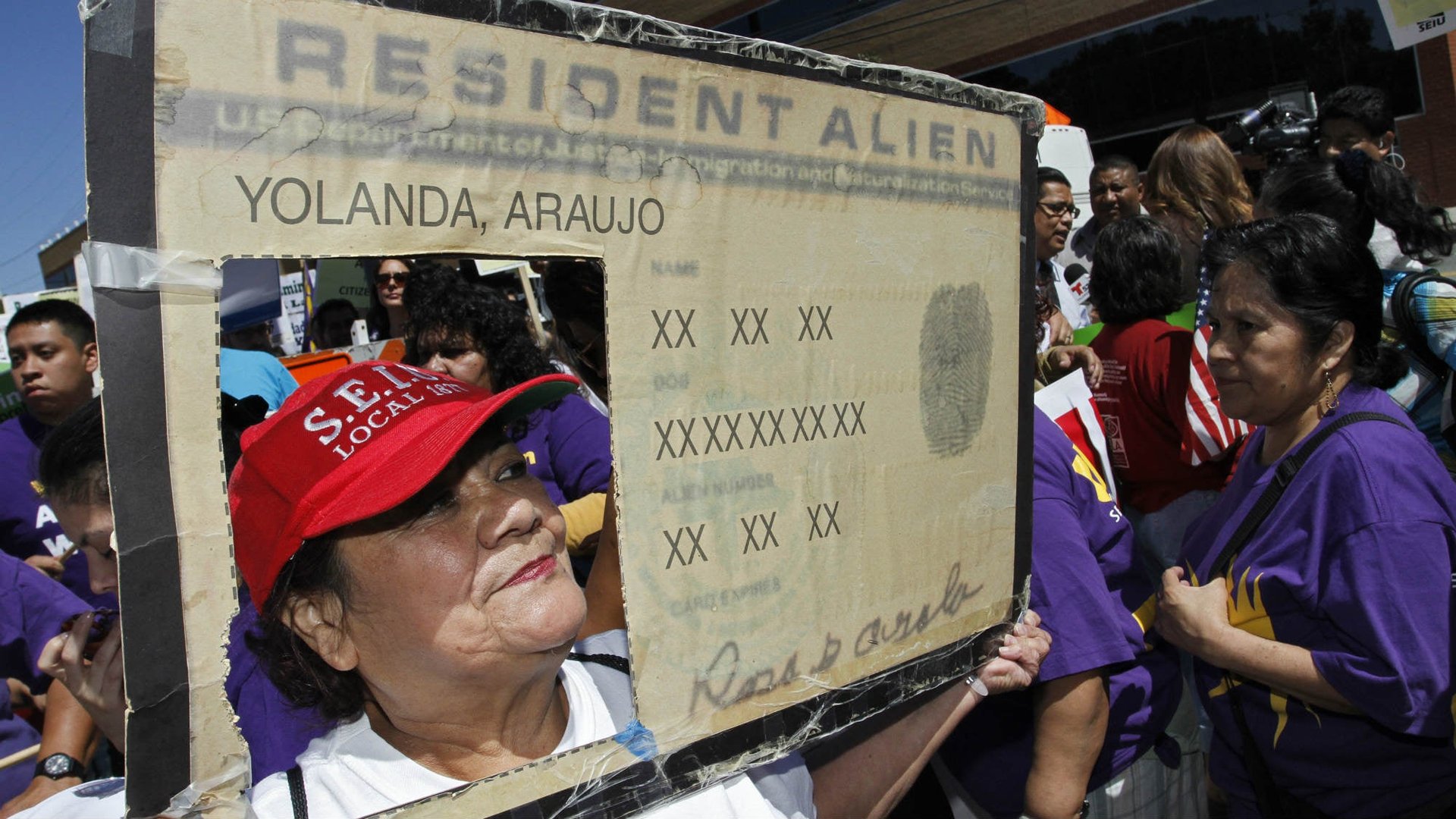

That’s just fine with Facebook and Google, which in the process of making internet users’ lives easier have become custodians of our online identities. Between them, the two web giants control more than 80% of the “social login” market, as third party sign-in is called. That grants them access to valuable data about what people are doing as they travel around the web.

Mobile operators have had enough of it. As data rather than voice or text becomes the big reason people use their mobile phones, networks want to extract more value from their users. At the moment, operators are mostly just the pipes through which data flow. But just as they made money from ancillary ”value added services” such as caller-back tunes and ring tones, they want to put the data to good use.

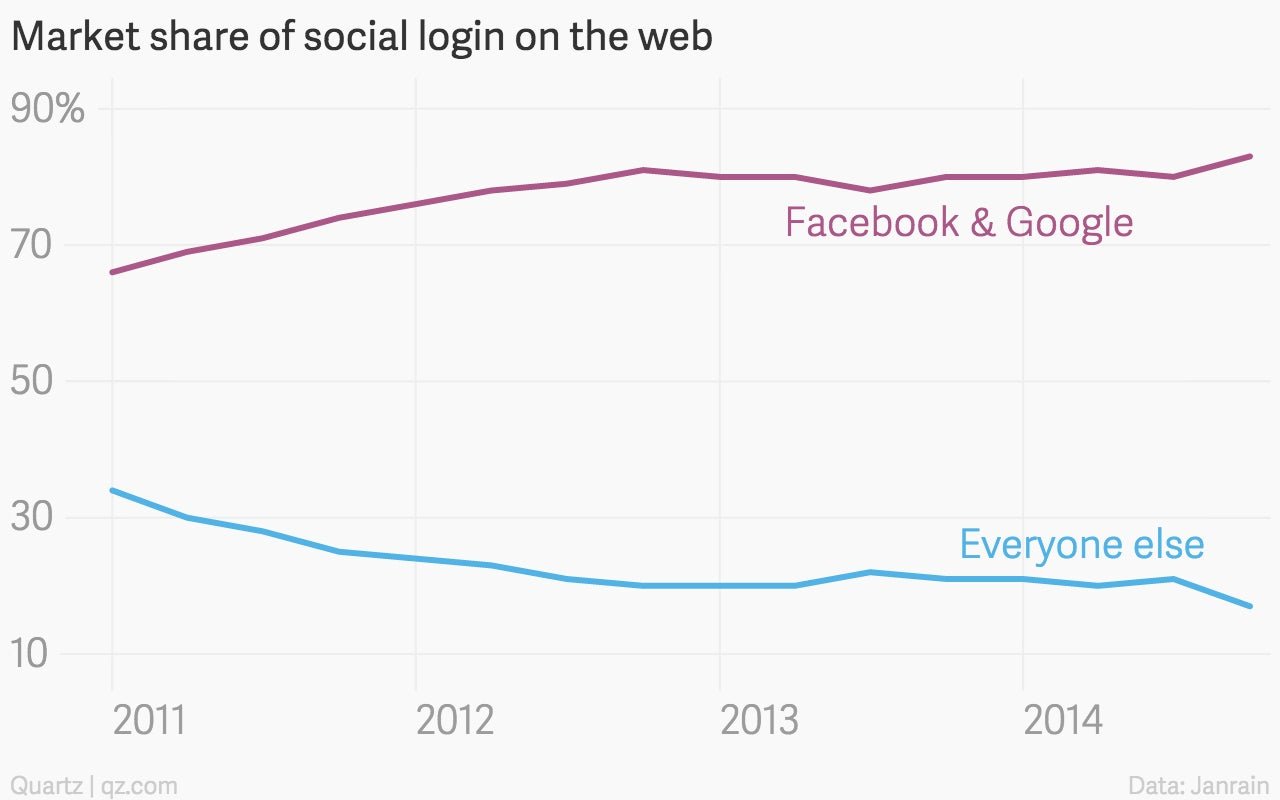

Identity is one way of doing that. And operators are counting on eliminating passwords as their ticket. Over the past year, the industry trade body, GSMA, has been rolling out Mobile Connect, a service that ties peoples’ identities to their phones rather than to a password. Here’s how it works:

As Mark Little of the GSMA puts, the hope for mobile connect is that it ”makes mobile operators more relevant in the ecosystems where they weren’t relevant.”

Some 17 operators in 13 countries have already signed up for the service, mostly in Asia and Africa, in countries including Bangladesh, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Cote D’Ivoire, Gabon, and Nigeria.

Many existing internet users are unlikely to stop signing into websites with Google and Facebook; it is more difficult to get people to change their behavior than it is to convince them to start off differently. But as hundreds of millions of people come online for the first time in the developing world—almost entirely through mobile phones—mobile operators finally have a chance to wrest back some control of online identity from Google and Facebook.