The racial divides of civil rights support, from Selma to Ferguson

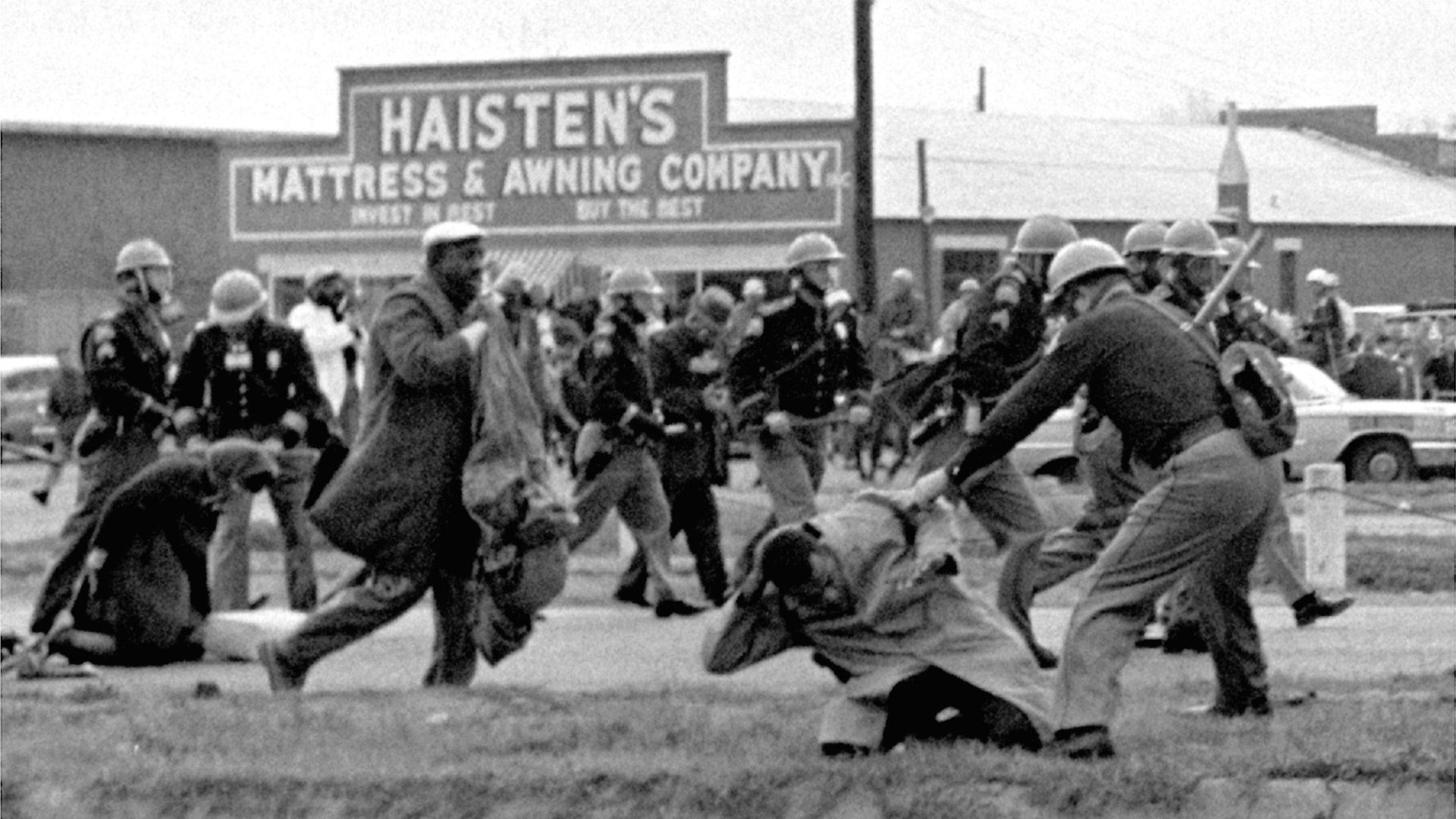

Fifty years ago, civil rights demonstrators began a march from Selma, Alabama, to the state’s capital of Montgomery, to advocate for voting rights and to protest the killing of an activist by a state trooper during an earlier demonstration. When Martin Luther King, Jr., Hosea Williams, and about 600 others set out on March 7, 1956, Alabama law enforcement met them with brutal violence. More than 50 demonstrators required medical treatment, and the day was dubbed “Bloody Sunday.” BBC then described injuries as ”skull and limb fractures and suffering the effects of tear gas.”

Fifty years ago, civil rights demonstrators began a march from Selma, Alabama, to the state’s capital of Montgomery, to advocate for voting rights and to protest the killing of an activist by a state trooper during an earlier demonstration. When Martin Luther King, Jr., Hosea Williams, and about 600 others set out on March 7, 1956, Alabama law enforcement met them with brutal violence. More than 50 demonstrators required medical treatment, and the day was dubbed “Bloody Sunday.” BBC then described injuries as ”skull and limb fractures and suffering the effects of tear gas.”

In May of that year, one in five Americans, including one in five white Americans polled, said they supported the state’s actions against demonstrators. No black Americans supported the state, according to the Harris poll (via Pew Research Center).

Three-fourths of Americans supported new voting rights legislation in April 1965, the Pew Research Center points out. In August 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits racial discrimination in voting. But that doesn’t mean all Americans felt that black Americans should be treated equally. Around 42% of Americans polled in February of that year said efforts to increase black Americans’ voting rights and desegregate public places were moving too quickly, the Pew story notes.

In August 2014, Americans protested 500 miles north of Selma in Ferguson, Missouri, after a white police officer killed an unarmed black teenager. Police responded to the protests with riot gear and tear gas. The demonstrators brought a long-brewing national conversation about police violence against black Americans into the mainstream. They were runners up for Time’s person of the year.

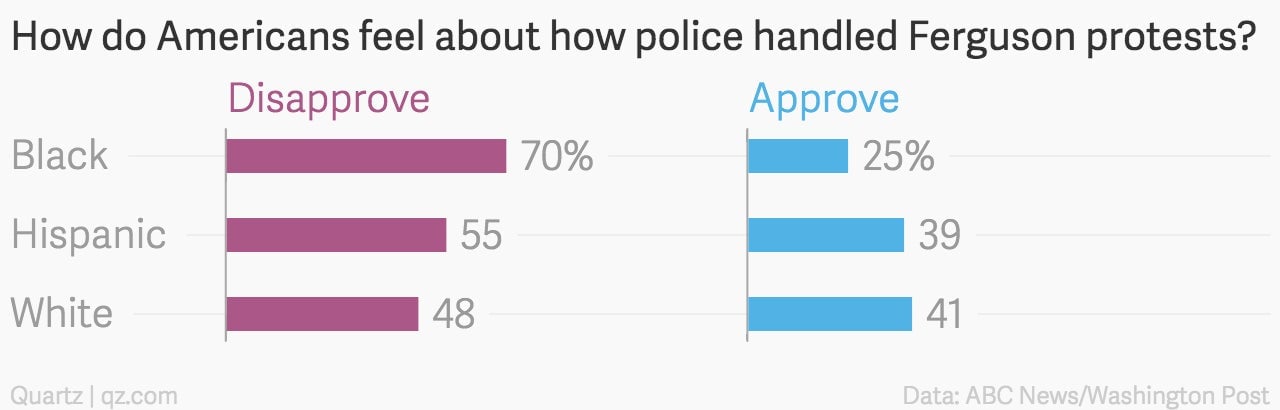

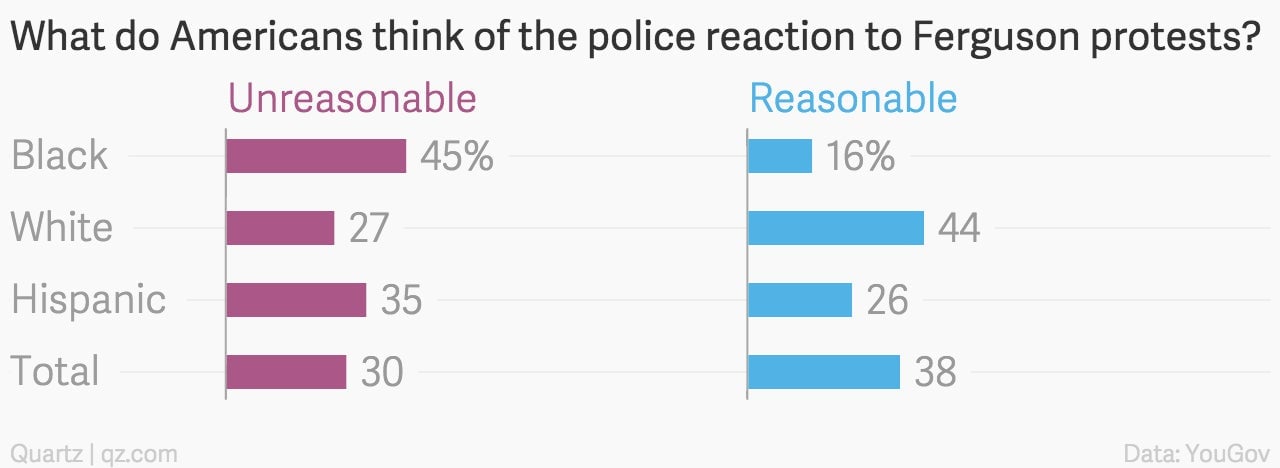

Yet both white and black Americans sided with police more last year than they did in 1965, according to November polls from Washington Post/ABC News (pdf, pg. 3) and YouGov (pdf, pg. 6).

The ABC News/Washington Post poll found that one in four black Americans supported the police actions, as did 41% of white Americans. That’s nearly twice as many white Americans as those who supported the state of Alabama in 1965, though they were still more likely to disapprove of the police response.

The other poll, from YouGov, found different results. Less than half of black Americans thought that the police reaction was unreasonable, and only one-fourth of white Americans found police reaction unreasonable.

Why do Americans seem to support police action against civil rights’ protests more today than in 1965?

One possible answer is that protestors are more difficult to support because it is harder articulate the problems they’re calling attention to, or identify solutions to them. As Time notes in a piece on the difference between the two movements, Selma’s activists had clearer demands than protestors in Ferguson: federal legislation to equalize voting. In Ferguson, and around the US today, the laws that are supposed to protect African Americans are in place (though as John Legend pointed out at the Oscars, the Voting Rights Act is being walked back). Just look at the Department of Justice report on Ferguson, which found that police criminalize black Americans as a source of revenue.