American taxpayers should pay close attention to General Motors’ stock buyback

In recent years, the leadership at General Motors has made much hay about its commitment to maintaining a “fortress balance sheet.“ (Essentially, that’s the finance-geek way of saying the company will be very cautious and sock away cash for one of the rainy days that regularly beset the highly cyclical auto business.)

In recent years, the leadership at General Motors has made much hay about its commitment to maintaining a “fortress balance sheet.“ (Essentially, that’s the finance-geek way of saying the company will be very cautious and sock away cash for one of the rainy days that regularly beset the highly cyclical auto business.)

But this morning, GM lowered the drawbridge to the fortress, if only a bit.

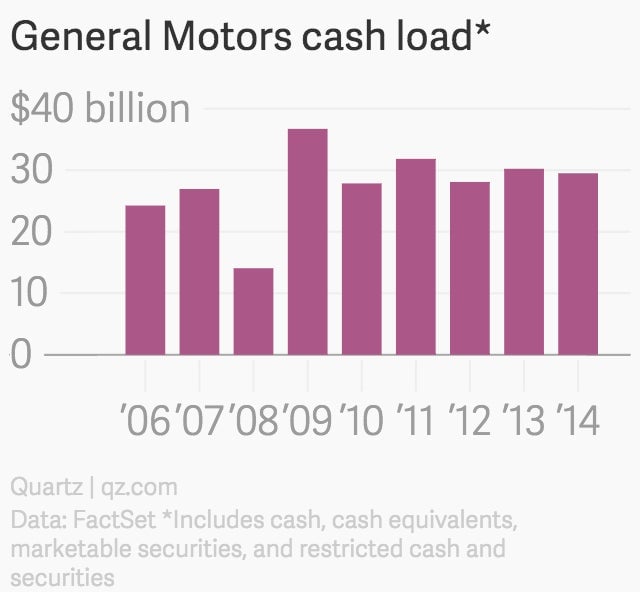

The company announced that it would spend $5 billion of its hard won cash to buy back shares. In conjunction with the buyback announcement, GM said that a group of activist investors had relented in their push for a board seat and a larger buyback of $8 billion. CEO Mary Barra also announced that it was lowering its target for the amount of cash it needs to keep on hand to $20 billion. (The automotive business’s cash balance was roughly $25 billion at the end of 2014.)

The stock market welcomed the news; shares rose about 3%. But today’s announcement isn’t just relevant to shareholders. It involves the American taxpayer, who was called upon to shell out $49.5 billion in 2009 to ensure that General Motors survived its bankruptcy filing. Last year, a government watchdog estimated that taxpayers ended up spending more than $11 billion on the deal. (Though it might have been money well spent in terms of preventing a full-scale implosion of the US auto industry.) Through the bailout, the US government became a part-owner of GM, which it remained, until finally selling its stake in December 2013.

If GM ran into trouble again—and its cash cushion wasn’t big enough to avoid another potential bankruptcy—the US government might be called upon to come to the rescue once more.

There’s no indication that we’re anywhere near such a crisis. But it should be noted that GM had more than $20 billion in cash on hand in 2007, just a few years before it was forced to declare bankruptcy. For its part, General Motors argues that since its post-bankruptcy restructuring, it’s no longer the same bloated company. For instance, it has moved from eight brands to four, and pared back significant chunks of its manufacturing capacity.

“We need to have the right amount of cash on hand to run the business,” says Tom Henderson, a GM spokesman told Quartz. “And after an assessment of our operating needs and what could happen in the future, $20 billion is the right level.”

Still, there are clearly some clouds on the horizon. GM is wrangling with weak auto markets in Latin America and a downright ugly one in Europe. It has contract negotiations with the United Auto Workers in 2015, which might be complicated by shoveling cash out the door to shareholders ahead of time. It will likely have to fork out significant sums to deal with the ongoing recall mess related to faulty ignition switches. Moody’s analysts note:

GM will also have to contend with the highly cyclical nature of the auto industry and its vulnerability to unexpected shocks. One of the fundamental ways of contending with the risks in this industry is to have a robust liquidity profile. The liquidity position that GM has chosen to run with as a result of this new shareholder distribution plan remains adequate, but will be notably less robust than it would have otherwise been.

Moody’s didn’t cut GM’s bond rating after the move. But it’s clear that today’s announcement represents a shift away from the concentrated caution that has characterized the company’s financial management in the immediate aftermath of its bankruptcy. Taxpayers should take note, since they would likely be on the hook if something were to go horribly wrong again.