It’s time for Italians to forget about Silvio Berlusconi

On March 10, the latest chapter of Silvio Berlusconi’s never-ending judicial saga was written: Italy’s highest court upheld the acquittal from charges of having sex with Karima El Mahroug, an underage prostitute and—a much more serious crime in the Italian penal code—of abusing his official authority to demand that police release the girl, accused of theft, saying she was a niece of then-Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak.

On March 10, the latest chapter of Silvio Berlusconi’s never-ending judicial saga was written: Italy’s highest court upheld the acquittal from charges of having sex with Karima El Mahroug, an underage prostitute and—a much more serious crime in the Italian penal code—of abusing his official authority to demand that police release the girl, accused of theft, saying she was a niece of then-Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak.

In his career, Berlusconi has been charged in 33 trials. He has been acquitted in seven. Eleven cases have been dropped. In seven cases, the trials went on for so long that they had to be dropped, too. Twice the crime he was charged of was no longer considered such, since he had the law changed. In two cases, amnesty was introduced. Three trials are still in progress.

All in all, Berlusconi has only been convicted once, for tax fraud.

Both Berlusconi’s supporters as well as his opponents have attacked the judicial system—whether for “persecuting” him or for not convicting him—but in either case it seems fair to say that his relationship with justice is, “complicated,” to say the least.

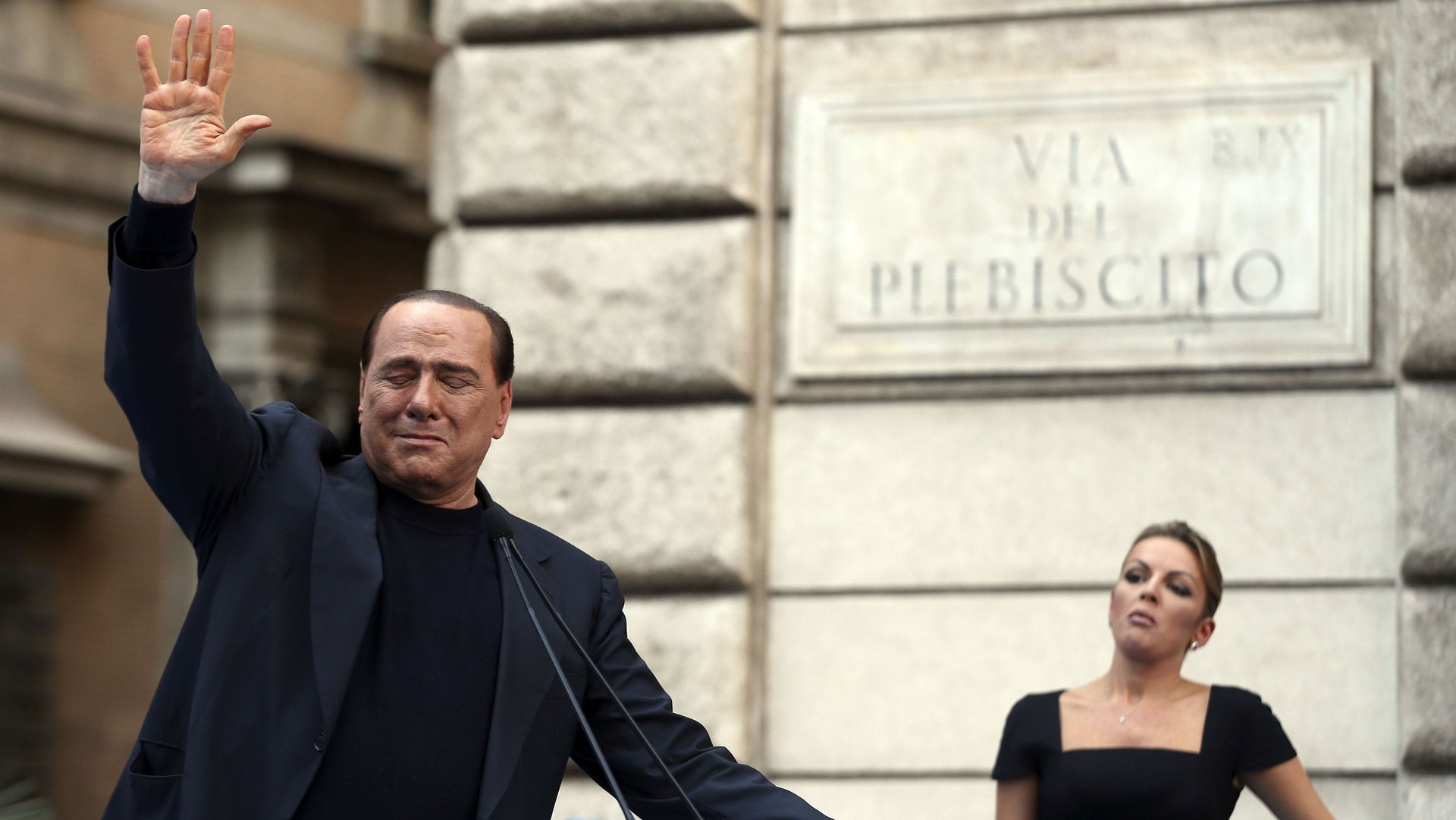

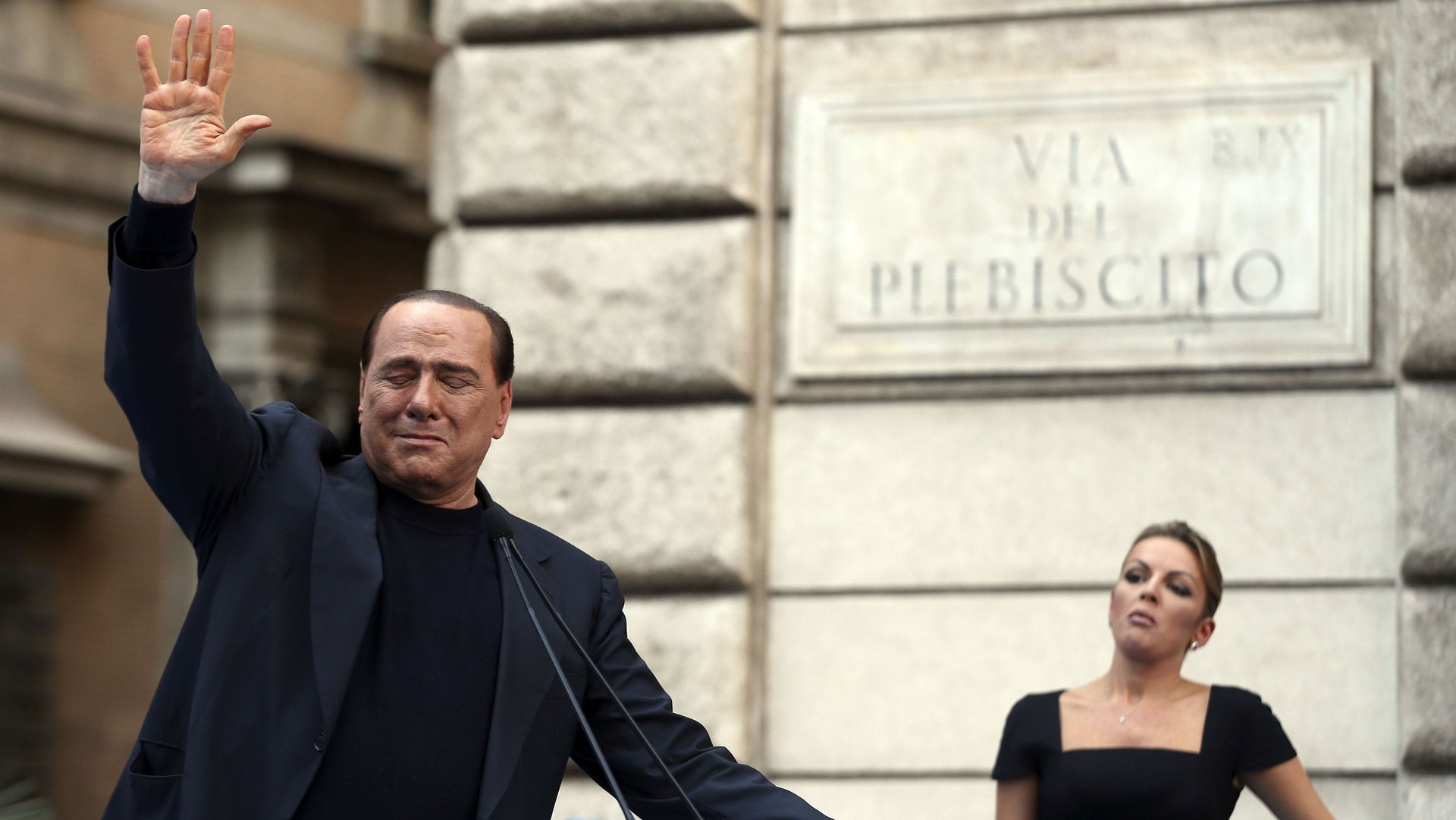

Berlusconi’s declaration after being acquitted was unequivocal: he’s “getting back to the field” (paywall)—his favorite metaphor to talk about joining politics again. “Adesso bunga bunga per tutti,” he joked (“and now, bunga bunga for all”).

The many who have opposed him through the years are outraged by the verdict. These are the same people who rejoice when Berlusconi is convicted, as if every verdict were a victory (or defeat) of democracy against a tyrant. Yet there is no point getting angry that Berlusconi got away.

Berlusconi is not a tyrant, and painting him as such is precisely what kept him in power for so long.

Yes, he is a media tycoon. Is it the sign of a great democracy when a candidate owns or otherwise influences most of the media? Of course not. Is that the reason behind Berlusconi’s political success? It’d be limiting to believe so, and it’s a condescending way to look at the “poor, dumb masses,” misled by the sparkle of bad television, while the intelligent Italians could see through him.

But it’s more complex, sadder than that even. Berlusconi embodies an ignorant, cunning, misogynistic Italy that reveres money over justice and power over honor. Like a dynamo that gains momentum by going, his years in politics have emboldened that Italy—and so it took over the media, the parliament, and the streets in a subtle yet unmistakable way. It has influenced the way people speak, the values they promote, the dreams they have. But make no mistake, it was organic, not an imposition.

Berlusconi was first elected prime minister in 1994. Between then and 2011, he’s been prime minister for a total of nine years over three terms. He’s been involved in innumerable scandals and run for office with pending charges more than once. He took on a country with some serious problems and when he was done with it, the public debt had doubled and the economy was in shambles. And yet, even after that, he still obtained a respectable amount of votes. Most importantly, in pretty much every election he’s always been a protagonist, because the entire Italian political sphere allowed him to be.

He was the actor without whom no political conversation existed. He was the one to beat. The enemy. The nightmare: even after he was condemned and had to leave public office, even after Matteo Renzi (perhaps because he bears a few similarities to Berlusconi’s political style) took the stage, he still remained a player, his shadow cast over the government through mysterious agreements with the prime minister.

Even outside the parliament, he has still been one to make deals with. And when political commentators note that his power is waning, they fail to underline the grotesque reality where a 79-year-old convicted fraudster, who admittedly threw sex parties in his home, still matters.

On the day after a fundamental reform of the senate and the constitution was voted in parliament (link in Italian), Berlusconi is on the front pages, and not merely for with the news of his acquittal—but for his reaction, for what he said and didn’t, for the fear of his return.

Berlusconi is a ghost that Italian politics can’t free itself of.

The analysts are right—there seems to be a decline (regardless of his acquittal). For the first time in over 20 years there seem to be different players—Matteo Renzi, and the new right-wing leader Matteo Salvini—today Berlusconi indeed appears weaker. Yet he—and the Italy he represents—has great resilience: if we start caring again, even just by getting angry at trial verdicts, we’ll end up giving him power.

Italy didn’t need Berlusconi to be convicted to put him out of the game. It needed a political sanction—”bastava non votarlo,” has been a refrain for years, “it would have been enough not to vote for him”—a big electoral defeat, for governing Italy like it were his own personal business. This didn’t happen—and likely never will.

There is only one thing we can do, if we want the Berlusconi era to truly end here—with an acquittal that is not a political victory. We just have to forget about it.

And, finally, move on.