A peninsula stretching south of the Alpide belt whose northern boundary is a breathtaking mountain chain. A land of wonderful—and wonderfully different—landscapes yet subject to devastating natural catastrophes. A place of many languages that share the same root yet are shockingly different from one another. A world of family values where mothers are venerated yet women kept at bay. A country of contrasts, of environmental disasters, crime and corruption; of superstition and creativity, of outstanding engineering and daily carelessness.

The exercise of finding similarities between India and Italy could continue ad infinitum. And yet another similarity has emerged during the Indian electoral campaign. In Narendra Modi, India’s political scene seems to have found what Italy has in Silvio Berlusconi.

Both Berlusconi and Modi rose to national power in the wake of big corruption scandals that called into question the party that reigned for decades in their respective countries: the Congress Party was involved in some of the biggest scandals in the history of independent India, and in 1994, when Berlusconi first ran for office, Italy’s Christian Democracy, the biggest party since the creation of the republic, was being dismantled following the “mani pulite” (clean hands) corruption scandal.

But it’s not so much in how each man was able to fill a void by selling a promise of modernity and change (Berlusconi’s “Italian miracle” sounds all too similar to Modi’s “Gujarat miracle“) that Modi’s climb to power resembles Berlusconi’s success. It’s in the dangerous way in which the entire political conversation in their country—amongst their supporters but even more prominently amongst their opponents—became all about them.

In his book Don’t Think of An Elephant!, George Lakoff emphasizes how important it is, during a political campaign, to not let the adversary control the conversation, regardless of who is in the lead. Because once you mention the elephant, it becomes impossible to imagine the conversation without it. It becomes impossible not to think about it.

Modi and Berlusconi are their countries’ elephants.

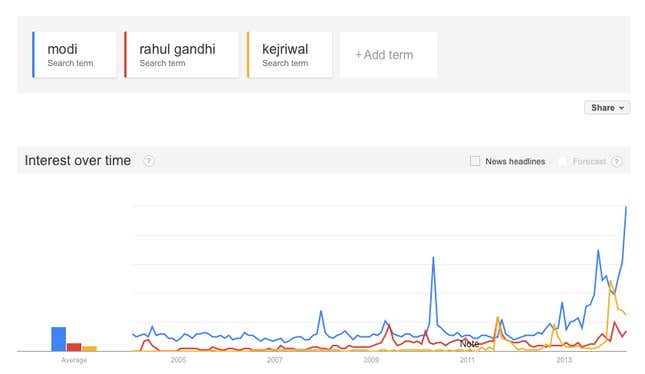

This election seems to be more about the leaders than about their parties, and more about Modi than it is about any other contestant. For someone who is still unlikely to win the absolute majority of votes, this campaign, at least from the outside, seems to be an awful lot about him. A Google Trend screenshot with a search for the three leading candidates, “Modi,” “Kejriwal” and “Rahul Gandhi” in the version (name and surname vs. surname) that shows a higher volume.

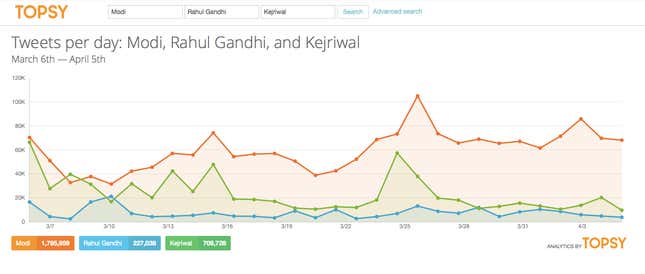

People talk about Modi. A lot. Hundreds of thousands of tweets a week, as shown by this screen shot of Topsy.com displaying the volume of Twitter conversations about the three candidates.

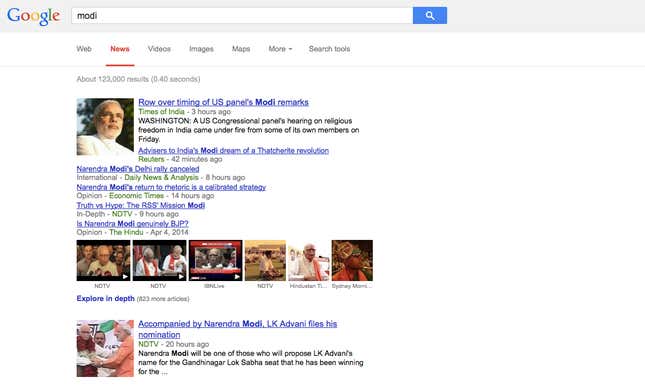

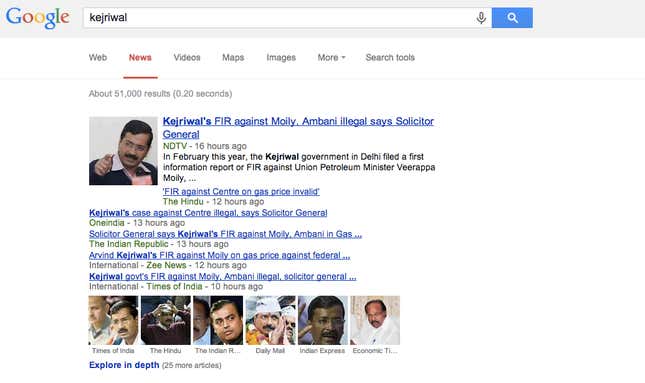

And news organization write about him more than they do about any other candidate.

Not all of these mentions of Modi are favorable, in fact, quite the contrary. But this is exactly how Modi becomes the elephant, just like Berlusconi did. People and news organizations speak in favor of Modi, but they are all the more vocal when it comes to speaking against him. And the more you mention the elephant, the harder it is not to think about him.

In Italy, what shaped the political debate in the past 20 years is arguably “anti-Berlusconismo“: the constant opposition he faced ended up reducing all the left-of–center’s thinking to a mere opposition to Berlusconi’s politics, and to him, without any original ideas.

During his last campaign, Berlusconi was confronted by a journalist who has been one of his most fierce watchdogs for years. (The interview is believed by many to be the occasion when he reversed his waning electorate until he managed to get about a third of the seats in parliament.) At one point he told the journalist, “I am the reason for your success.” That is true—and all those who made it a mission to expose Berlusconi’s mistakes and corruption somehow helped him maintain power for all those years.

An opposition, and a public opinion, that never stopped being obsessed with Berlusconi’s behavior, personality, and each of his mistakes made him the only true protagonist in Italian politics over the last two decades. Still, while he’s out of parliament and banned from public office, he maintain his role as both enemy and leader, a living ghost Italians can’t free themselves from.

Looking at the projections, it seems likely that India will give the Bharatyia Janata Party (Modi’s party) a great percentage of the votes. This is partially because during this campaign, Modi’s role became bigger and more cumbersome, till it filled everyone’s attention space.

At this point, the most effective communications weapon against Modi is to stop talking about him. Hard as it is. Telling a different story, one in which he’s simply a side character that becomes forgotten, is the way to have him, eventually, become one.