Putin’s disappearance is worrying, no matter when—or if—he resurfaces

Update: Vladimir Putin reappeared today for a scheduled meeting with Kyrgyz president Almazbek Atambaev in St. Petersburg.

Update: Vladimir Putin reappeared today for a scheduled meeting with Kyrgyz president Almazbek Atambaev in St. Petersburg.

Two things are important to watch in today’s news from Russia: is president Vladimir Putin alive, and is he still in power?

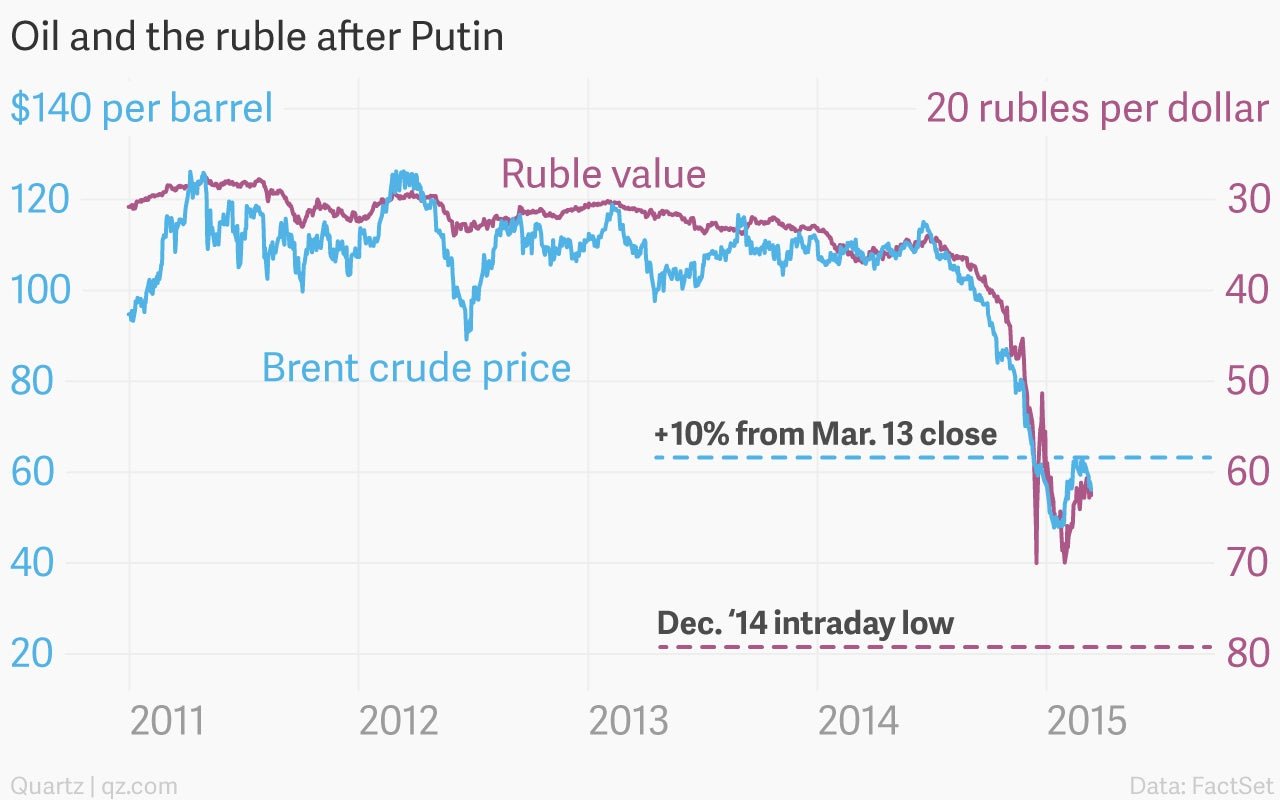

If the answer to either question is no, how will Russia and the world respond? From a financial standpoint, there is likely to be a Russian bond selloff and a plunge of the ruble, perhaps to its intraday low marked in December (see chart below). If we can take anything from the market reactions to the death two years ago of Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez, and the passing two months ago of Saudi King Abdullah, oil prices are likely to spike, at least briefly. But neither local nor global markets are likely to go into a deep and long free-fall. And oil isn’t likely to climb more than 10%, which would take it only to $57 a barrel or so.

It has now been 11 days since Putin was last seen publicly. And, absent any word from the Kremlin that could pass as a definitive fact, speculation has been rife variously that he’s been ill, doting over a new daughter, struggling for power, or otherwise occupied.

A few days ago, we scorned such speculation as the unseemly chattering of those wishing Putin ill. Yet on further contemplation, 11 days seems like a significant chunk of time with no word on the location of a man who controls the world’s second-largest cache of nuclear arms—he says he was prepared to use them (paywall) to defend the annexed territory of Crimea—and who, having whipped his nation into frenzied readiness to counter an alleged US plot to destroy Russia, still seems disposed to point out the nation’s enemies so that his people can march against them.

In Russia, the silent absence of a leader seems to pass as par for the course—and is perhaps yet another trick up the master deceiver’s sleeve to keep us all off balance. Putin’s tight circle of insiders, themselves possibly in the dark too, have been no help. As for those raising questions, they have been dismissed by Russian officials as chattering media classes forever looking for a story where there is none.

But the same would never be said of any other major world figure. If Barack Obama or Angela Merkel vanished without a trace for even a day, a desperate manhunt would likely ensue. If the disappearance lingered longer, you would possibly witness the collapse of the local currency and stock exchange, and knock-on global financial impacts, all based on the fear of foul play.

This is not an unreasonable reaction to Putin’s disappearance, either. It is truly time for the world to find out where and how he is.

What are the possible explanations?

In no particular order:

1. Putin has the flu, had a botox reaction, or is otherwise incapacitated

2. He is dead.

3. He is with reputed girlfriend Alina Kabayeva while she gives birth.

4. He is on holiday.

5. He is in the midst of a power struggle.

7. He is diverting attention from some other event.

8. He is just messing with us.

Here at Quartz, we remain convinced that the likeliest scenario is that Putin is fine, but again we also think we are not witnessing business as usual.

If Putin has fallen, there is good news and bad news

For all his pugnacity, Putin is probably a moderating influence on the intelligence and security officials who are his power base. If he is gone, his successor is likely to try to consolidate power through a more intense political crackdown and more foreign adventurism.

Russians themselves are unlikely to resist. Given the propagandistic political preparation carried out under Putin over the last year, it will be dead easy to persuade the public that a dastardly western plot is to blame for Putin’s exit.

This would bad news for the existing business sector—when he consolidated power, Putin eliminated much of the existing well of industrial oligarchs, and swapped in his own. He forced major western oil companies that signed deals under president Boris Yeltsin into altered contractual arrangements. BP, Shell and Total lost rich oilfields in all or part, and ExxonMobil had to accept different export arrangements from what it expected for natural gas in its Sakhalin I field. Over time, a new leader in the Kremlin is likely again to throw both local and international business arrangements into upheaval.

Now for the less-bad news: Despite its recent economic turmoil, Russia is not at risk of running out of money, at least not immediately. The country has a low debt burden and the majority of its bonds are owned by domestic investors. Moody’s ratings agency expects Russia’s foreign-exchange reserves to fall by half over the next two years, to around $135 billion or levels last seen in 2005, and for the economy to shrink by more than 8% altogether in 2015 and 2016. But that was going to happen anyway, absent any problems with Putin’s staying power.

An acceleration of capital flight following a messy political transition would erode Russia’s buffers. Any disruption to energy exports would make matters even worse, given that Russia runs a deficit of more than 10% of GDP when oil and gas are excluded from its budget, but this scenario is unlikely. Russia will continue export its hydrocarbons.

Tapping sovereign wealth funds and imposing capital controls—limiting bank withdrawals and forcing the repatriation of foreign investment—could buy time and scare up enough cash for a new government to pay its creditors. Reversing recent interest-rate cuts would probably also be considered, which would keep more money in the country.

But there would still be one big question: what really happened to Vladimir Putin?