The level of black unemployment in the US is crisis-level for everyone else

The Federal Reserve’s monetary policy committee is cloistered in Washington today, Mar 18, working out how to move the economy forward, and the biggest question it faces is when to raise interest rates and shift to a slightly less supportive role for the economy. The latest policy pronouncement is due this afternoon; look to see whether the committee will remove the word “patient” from a key section on how it will approach raising interest rates.

The Federal Reserve’s monetary policy committee is cloistered in Washington today, Mar 18, working out how to move the economy forward, and the biggest question it faces is when to raise interest rates and shift to a slightly less supportive role for the economy. The latest policy pronouncement is due this afternoon; look to see whether the committee will remove the word “patient” from a key section on how it will approach raising interest rates.

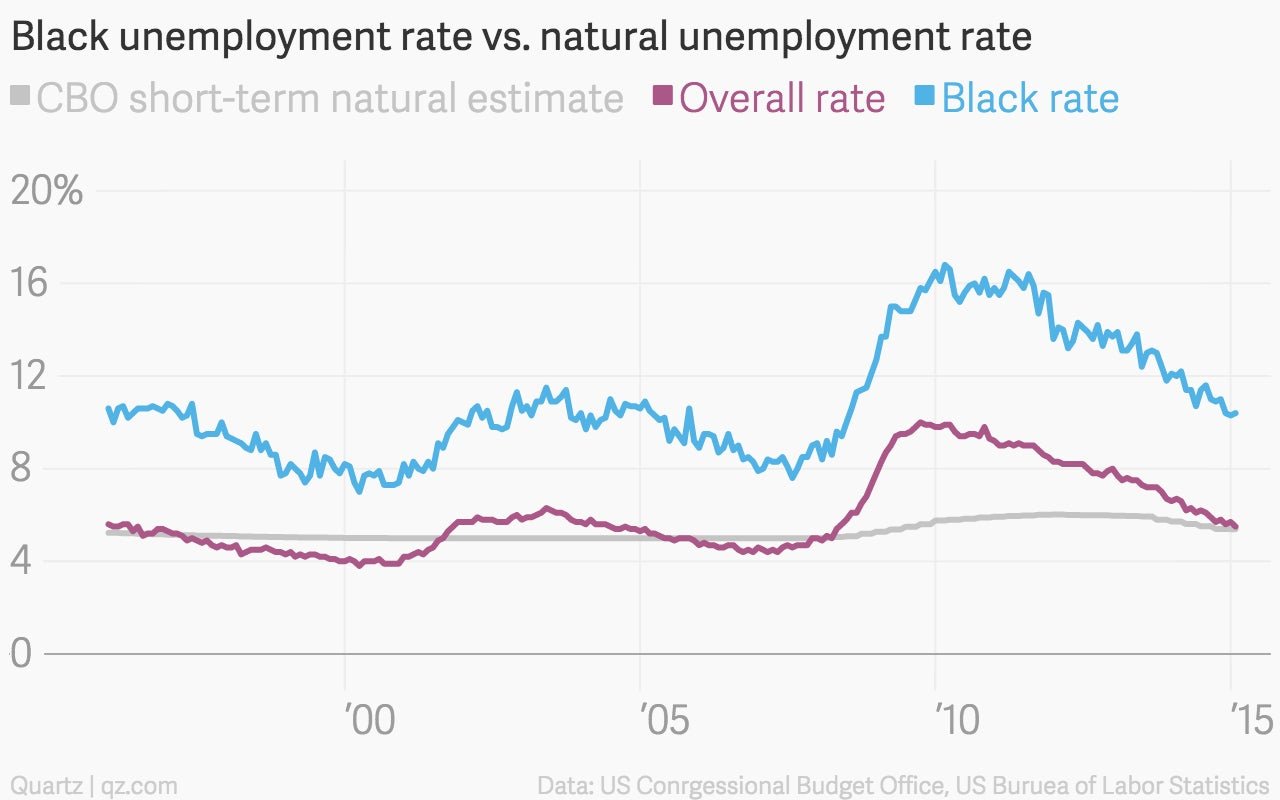

Despite a mixed bag of economic indicators (paywall) over the past few months, Fed watchers are keeping a close eye on the falling unemployment rate and its growing proximity to its so-called “natural level.” The natural rate of unemployment, also known as the the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment—NAIRU—is a rough estimate how low the unemployment rate can go without starting to drive up inflation.

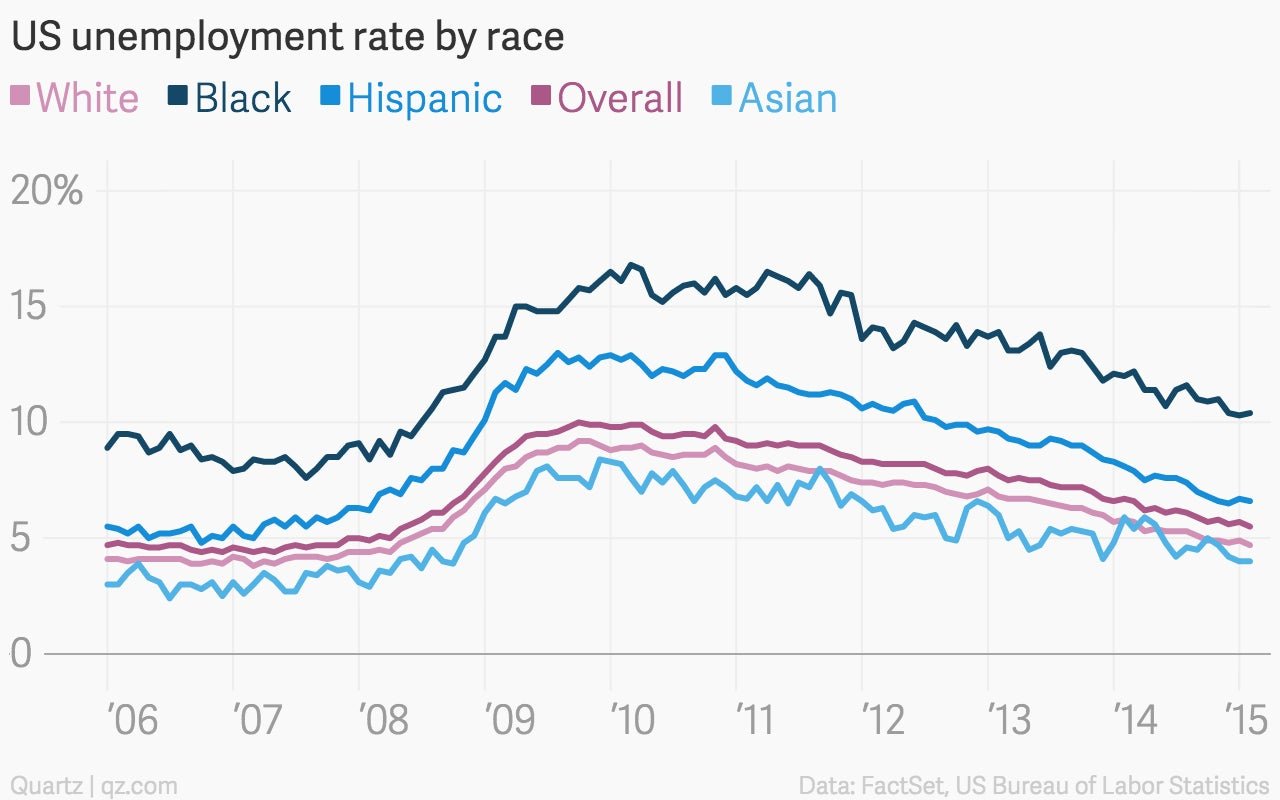

But the notion that current levels of unemployment might be natural has to sting for huge chunks of the American populace that have yet to recover from the Great Recession. For example, the black unemployment rate in February was 10.4%, higher than the country’s overall unemployment rate of 10% during the worst moments of the Great Recession.

“We’re not saying that Federal Reserve policy will eliminate unemployment disparities, but it will have an effect on how low the black unemployment rate goes, as well as the overall rate,” says Valerie Wilson, of the Economic Policy Institute. “If things were to slow down now, the black unemployment rate is still above 10%.”

Of course, the Fed doesn’t aim monetary policy at solving ills of any specific group. Monetary policy isn’t the best tool to deal with factors that drive higher rates of black unemployment: high incarceration rates (paywall), substandard education (for black men, anyway), and plain old structural racism, all play a part. (A recent paper in the journal Social Forces showed that black Harvard grads have the same job prospects as white alums of less-selective state schools.)

“I think what the Fed would say is that the monetary policy had to be based on the economy as a whole,” says the Urban Institute’s Robert Lerman. “And the fact that monetary policy is run in the right way doesn’t mean it will solve all problems.”

Still, even as the Federal Reserve seems set on turning the page on the era of the Great Recession, it’s worth remembering the economic pain of remains real for many millions of Americans, especially within minority communities. Black median household wealth was nearly halved during the Great Recession, falling from $19,200 in 2007 to $11,000, or roughly one-thirteenth the wealth of a median white household. That’s the largest gap between white and black wealth in a quarter century.

Viewed through that lens, there’s not a lot that feels “natural” about the US economy right now for many Americans.