Creating Singapore: The life of Lee Kuan Yew

The forthright and farsighted Cambridge-trained lawyer who transformed Singapore from a colonial entrepot in Southeast Asia to one of the world’s most important financial centers has died.

The forthright and farsighted Cambridge-trained lawyer who transformed Singapore from a colonial entrepot in Southeast Asia to one of the world’s most important financial centers has died.

Lee Kuan Yew, the city-state’s founding prime minister and one of Asia’s most prominent statesmen, had been in the hospital on life support for several weeks, suffering from severe pneumonia. He was 91.

“The Prime Minister is deeply grieved to announce the passing of Mr Lee Kuan Yew, the founding Prime Minister of Singapore,” says a statement on the prime minister’s official website. “Mr Lee passed away peacefully at the Singapore General Hospital today at 3:18am.”

For much of his adult life, Lee dominated the politics of this small island nation, assembling the People’s Action Party (PAP) in 1951 and ensuring its control over Singapore for half-a-century and counting.

While Lee’s undeniable talents that propelled Singapore’s meteoric rise will define his legacy, the man sometimes described as Asia’s Henry Kissinger also leaves behind a country at the crossroads.

“We are at an inflection point,” his son and incumbent prime minister Lee Hsien Loong said in a 2013 speech, “Our society is more diverse, our economy is more mature, our political landscape is more contested.”

The Singapore that his father inherited and helped build when he was prime minister between 1959 and 1990 is now an entirely different country. And Lee’s passing could potentially trigger a shift in Singapore’s political and economic landscape.

Kampongs to casinos

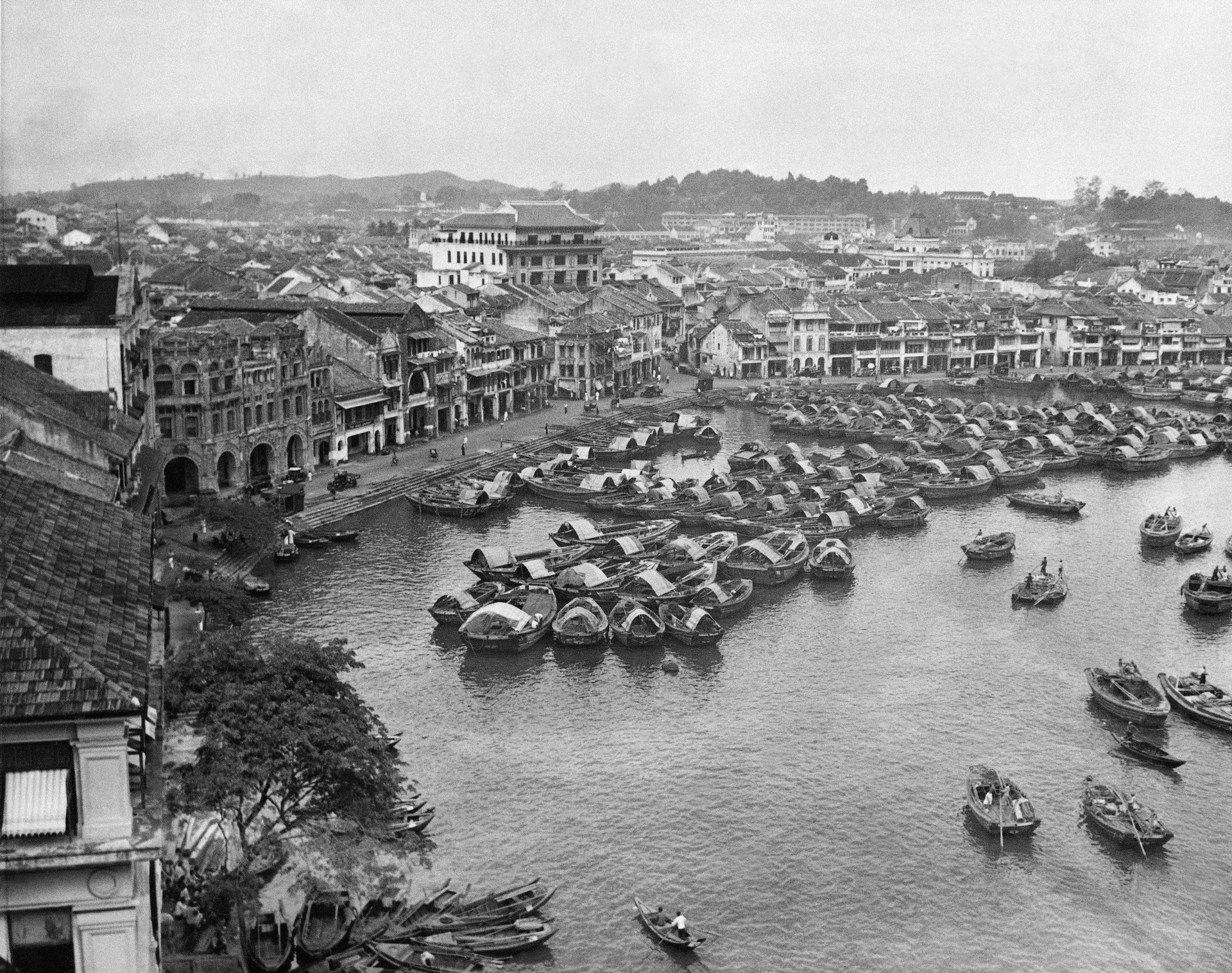

Singapore was barely a shadow of the economic powerhouse that it is today when it was expelled from Malaysia and became an independent nation in 1965. After hundreds of years of colonial rule as part of “British Malaysia,” the island had been invaded by Japan in WWII and left in a shambles. Its population was a mix of traders, former indentured servants, escaped convicts and businessmen, who frequently clashed along economic and racial lines.

“…Singapore was doomed to live on the wits of its people,” The Economist (pdf) wrote of the separation, “They were not a promising mix.”

Instead of falling apart, though, Singapore thrived. Ramshackle single-storied houses in rural kampongs—Malay for villages—have now given way to an iconic glass and steel skyline complete with some of the world’s most profitable casinos where Asia’s second largest concentration of millionaires (after Qatar) can burn some cash.

This city-state of a little more than 715 square kilometers is now one of the richest countries on the planet, in terms of per capita GDP, with an economy entirely incommensurate for its tiny size.

And this ambitious growth trajectory was engineered under Lee’s close supervision. Bereft of any natural resources, a young prime minister pushed the island to develop key infrastructure, including a world-class port and an airport.

Alongside these projects, Lee focused on housing and jobs—Singapore’s preceding British overlords had other concerns—and established the foundations for the Housing Development Board (HDB) and the Economic Development Board (EDB).

The HDB transformed this swampy island into a first-rate, first-world metropolis, and helped pull Singaporeans—of Chinese, Malays and Indian descent—out of their ethnic enclaves and into carefully planned mixed townships. The EDB, meanwhile, slowly built up Singapore’s mix of industries and businesses, dodging recessions and crises to assemble an economy that could support a population swiftly moving out of poverty.

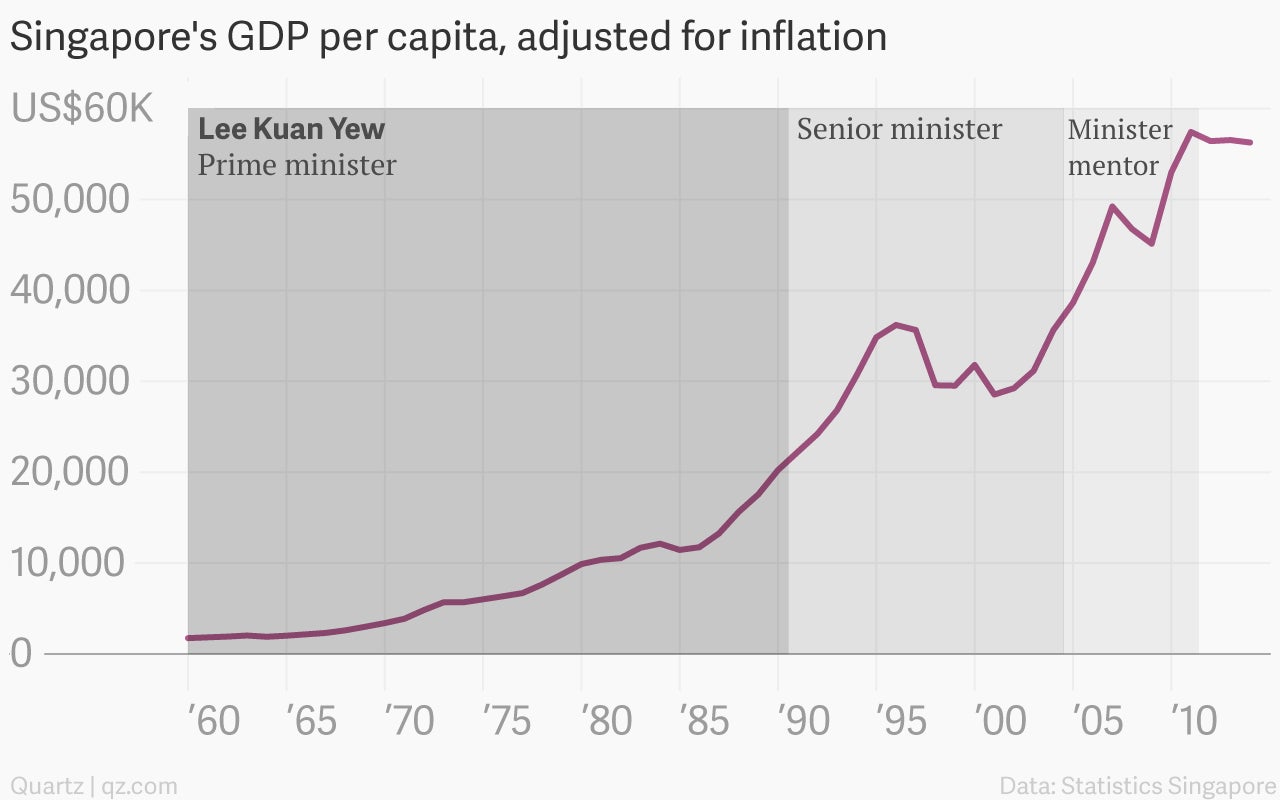

From a per capita GDP of about $500 in 1965, Lee’s administration raised it a staggering 2800% to $14,500 by 1991.

It came with a price, however: Little room for dissent, debate or a free press.

Yet, in under three decades, the little “red dot”—as a sneering Indonesian president once described Singapore—had become an unlikely Asian success story, with diplomatic clout that belied its size.

And Lee, the son of a Shell Oil storekeeper, established himself as a statesman of reckoning, having steered Singapore through the treacherous geopolitics of the East and the West.

“When Lee Kuan Yew speaks,” the introduction to a 2013 book on Lee observed, “presidents, prime ministers, diplomats, and CEOs listen.”

Whither Singapore?

By the time Lee stepped down as prime minister in 1990—remaining “senior minister” till 2004, and “minister mentor” till 2011—Singapore’s remarkable turnaround under his leadership was indisputable. Instead, the question was whether it was sustainable.

And few understood that better than Lee himself. “Singapore cannot take its relevance for granted,” he said in a 2009 speech. “Singapore has to continually reconstruct itself and keep its relevance to the world and to create political and economic space. This is the economic imperative for Singapore.”

But Lee’s son, the current prime minister, has inherited an entirely different Singapore than what his father had to reinvent 50 years ago.

The once unshakeable political domination of the PAP is fraying. The general elections in 2011 was the worst ever for Lee’s party since independence in 1965, although the PAP remained in control of 81 out of 87 seats in parliament. Then, in 2013, the opposition wrested control of another seat in a by-election, with the widest margin in decades.

And the next general elections will be a “a deadly serious fight,” the prime minister said last year, a far cry from the years between 1968 and 1981 when the PAP won every seat in every election.

The political downfall has been so extraordinary for a party once so completely in control that, after the 2013 by-election debacle, Singapore’s widely-respected former foreign minister, George Yeo, publicly wondered on Facebook: “Whither Singapore?”

Tightrope

Much of this electoral disgruntlement has to do with the widening income gap in Singapore, which is also the world’s most expensive city to live in. Despite the wave of prosperity that has washed over this city-state in recent decades, it has one of the highest Gini Coefficient—a measure for wealth inequality—in the developed world. Low income families in the country are struggling to make ends meet, even as the government is pouring more money into subsidies.

As ordinary Singaporeans falter, the success of better skilled immigrants—and their growing numbers—has increasingly caused friction, forcing the government to cut back on foreign workers.

Non-resident population growth (pdf), as a result, dropped to 2.9% in 2014, compared to 4% in 2013. Foreign employment growth also fell to 3% in 2014, from 5.9% in 2013.

That is unlikely to help an economy built on overseas talent, instead risking slowing it down precisely when the government could do with more money to share.

Still, resentment against immigration runs so deep in certain sections that Singaporeans staged a mass rally—a very rare event in a tightly-ruled country—in 2013 against a government paper that forecast rising numbers of foreign residents.

And that’s the tightrope that prime minister Lee—or whoever replaces him in 2017—must negotiate, seeking to balance sustained economic growth with the rising aspirations of this developed Asian country.

In his time, of course, Lee Kuan Yew made it all look rather easy.