Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew, the 91-year-old founding father of one of Asia’s smallest but most powerful economies, has died. The former prime minister, who had been in the hospital for over a month with severe pneumonia, leaves behind a city-state whose current success is built on policies he put in place decades ago.

Lee led Singapore from a colonial backwater under British control to one of the world’s most thriving financial centers, and he did so with a tight grip on power. He has been criticized for instituting wide-reaching censorship, limiting civil rights, discriminating against gays and migrant workers, and generally maintaining a one-party autocracy for almost half a century.

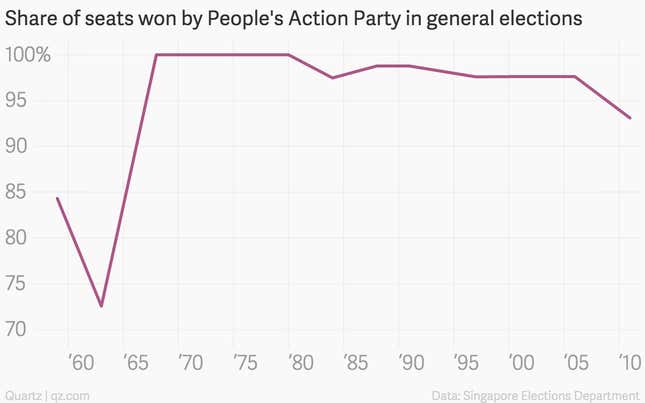

Lee was able to maintain that autocracy, though, because of the huge popularity of his People’s Action Party, which captured most—if not all—of the seats in Singapore’s parliament in the country’s history as an independent republic:

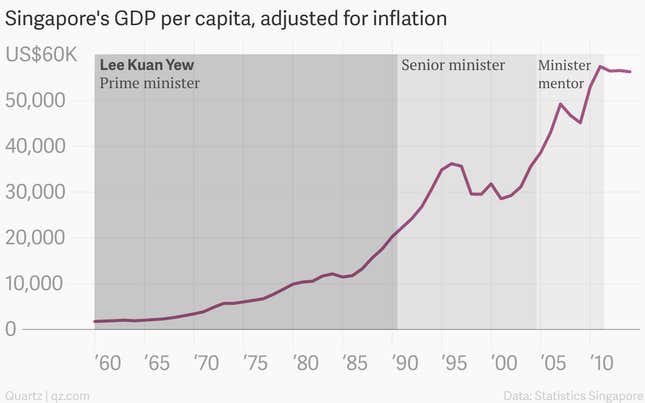

That’s because Lee engineered one of the world’s most impressive growth stories—one that everyone from American Republicans to Chinese communists have both openly envied. (“Benevolent dictatorship has never looked so good” one columnist wrote of the Singapore in 2012.)

The tiny, resource-poor country’s GDP per capita skyrocketed under Lee to one of the highest in the world, behind just oil-rich Qatar and private banking center Luxembourg, according to the IMF. Under his successors that growth has only accelerated:

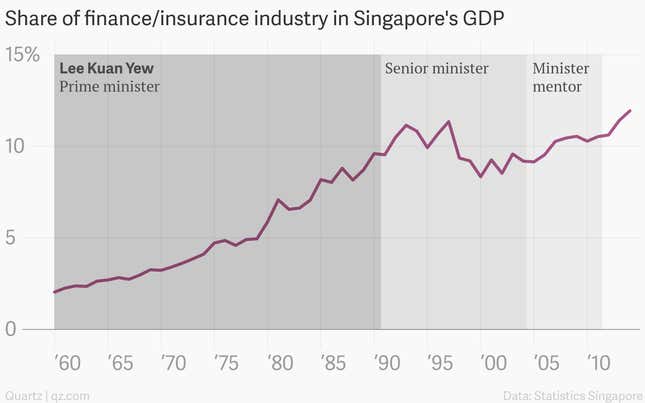

Key to Singapore’s transformation was the creation of an Asian financial center that now rivals Hong Kong, and contributes over 10% of the country’s GDP. As far back as the 1970s, Singapore’s finance industry proved itself adept at taking advantage of global upheaval, wooing banks, bankers and off-shore investment with tax breaks and less-onerous, more predictable regulation than its rivals.

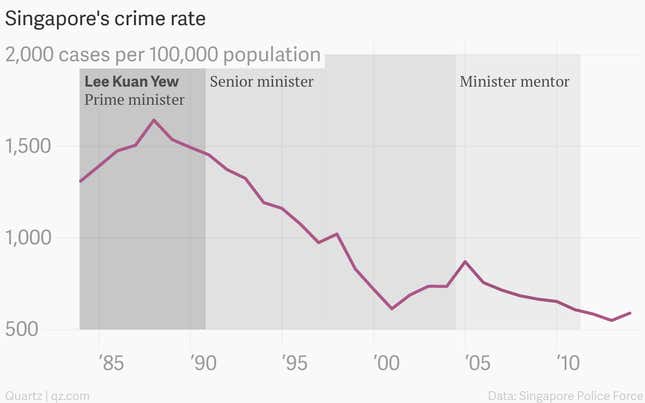

Meanwhile, the one-party autocracy rolled out strict punishments for even minor infractions, a model that has helped drive Singapore’s crime rate to one of the lowest in the world.

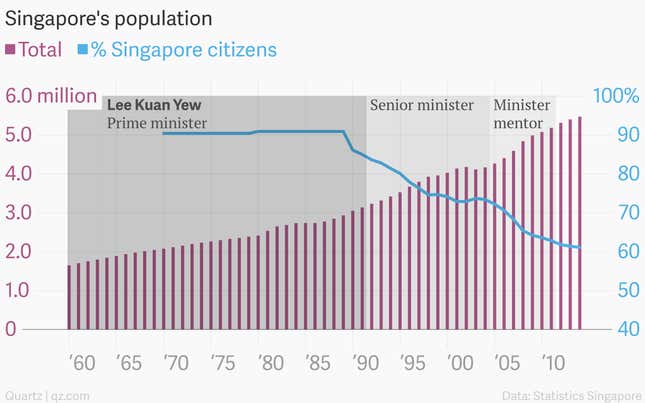

The country’s safety and prosperity has drawn masses of immigrants, who are crucial to powering the country’s large business sector—the city-state’s unemployment rate has hovered around only 2% for years. But as the share of foreign-born residents rises, it has put pressure on politicians to curb the influx of immigrants on behalf of locals, ease restrictions for the benefit of businesses, or try to come up with inevitably messy compromises in the name of maintaining its economy’s competitiveness.

It’s uncertain how Singapore will fare following Lee’s death. He is believed to have kept a tight hold on power through his son, Lee Hsien Loong, the current prime minister, sometimes called “BG Lee” or “seed of Lee” in Malay. His ruling party lost six of the 87 seats in parliament at the latest election, in 2011, suggesting new fissures in in the country’s politics.