Marc Andreesen explains the difference between Apple CEOs Steve Jobs and Tim Cook

“The Apple playbook under Steve Jobs was a single playbook,” declared Silicon Valley investor Marc Andreessen at last night’s Quartz event in New York City. “He would invent a new product category, start with 100% market share, and then every day that goes by, lose market share until some terminal outcome.”

“The Apple playbook under Steve Jobs was a single playbook,” declared Silicon Valley investor Marc Andreessen at last night’s Quartz event in New York City. “He would invent a new product category, start with 100% market share, and then every day that goes by, lose market share until some terminal outcome.”

In the case of the Macintosh computer in the late 1990s, that “terminal outcome” was a market share that hit bottom at around 2% of the share of PCs, says Andreessen, with Windows and Linux-based PCs comprising the rest.

Steve Jobs, says Andreessen, “didn’t care about market share,” and was focused instead on the margins and “pricing umbrella” he could achieve by selling high-end products to a subset of consumers willing to pay a premium. This strategy worked for Jobs in part because he was confident that even as his products lost market share, he could always simply invent the next great thing and start the cycle all over again.

Tim Cook is different, in Andreessen’s estimation. He’s more focused on market share than Jobs was, and may try to engage competitors like Google and Samsung directly, in an attempt to hold onto as many users as possible. (Andreessen didn’t say this, but it’s always the elephant in the room when comparing Steve Jobs to Tim Cook: Will Cook and his team prove to be as much of a genius as Jobs was at inventing whole new categories of gadgets?)

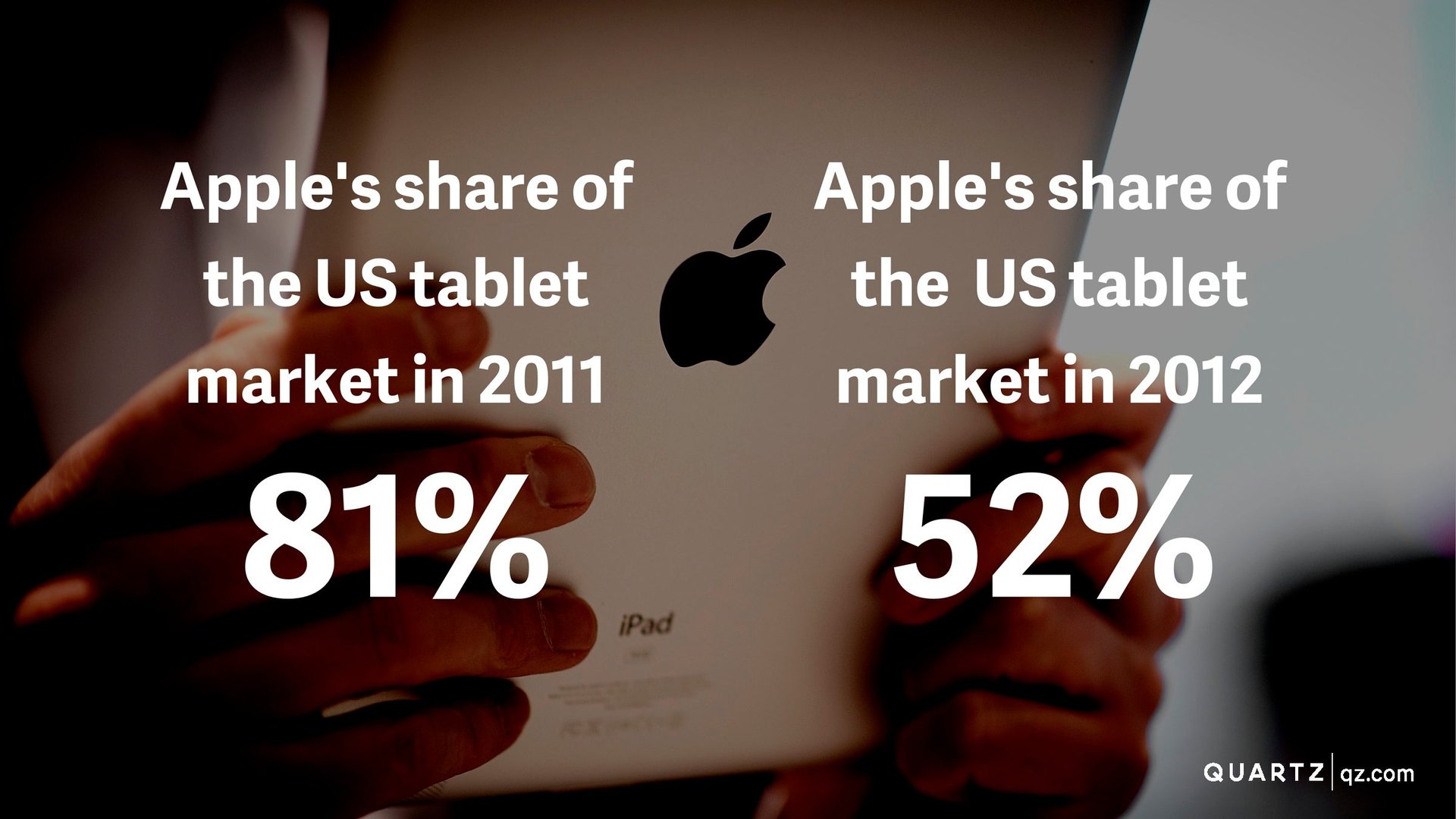

“The question is, will Tim Cook push Apple more aggressively into the market share battle,” says Andreessen. He cites the iPad mini, a device designed to defend Apple’s share of the tablet market against smaller and cheaper Android-powered 7″ tablets, as evidence that the company is willing to sacrifice margins in order to capture customers. Another example is Apple’s post-Jobs tendency to keep older models of the iPhone available longer, in order to capture customers who can’t afford the latest model.

“He hasn’t declared war yet,” says Andreessen. “In the long run in these markets, if you’re not the majority market share, you don’t have the majority of the apps.”

This is an important point about software ecosystems in general, and especially the iPhone and iPad, which run on iOS. One reason consumers are willing to pay a premium for these devices is that they’re the ones for which developers are building the most apps. If Apple can’t hold onto market share, it could face the same difficulties that it did when the Macintosh computer was at its nadir, and much of the software that was available for Windows couldn’t be had on a Macintosh.

One thing that’s worth adding, and this was not part of Andreessen’s analysis: Even under Steve Jobs, there is at least one instance when Apple played, and won, the battle for market share: The iPod.

In the world of music players, Apple grabbed and then steadily increased its market share, which has stayed above 70% through 2012. At this point, the “terminal outcome” for the iPod is its replacement by the touchscreen smartphones that Apple itself pioneered.

It seems inevitable that Apple will lose the battle for smartphone market share—Andreessen guesses that the company will bottom out at around 15% or 20% of the market, with Android capturing the rest. But if Tim Cook follows the iPod playbook for the tablet market, where Apple is (just barely) still dominant, we should expect to see as many devices at as many price points as consumers may demand. In a way, we’re there already: the iPod touch, iPad Mini and iPad represent a spectrum or products reminiscent of the variety of iPods Apple has long sold. It will be a tough battle, however, with competitors like Google and Amazon willing to sell their devices at cost as they tap into revenue streams that Apple has yet to capitalize on.