Online bespoke menswear has gone mainstream

There’s no room for ego when getting fitted for a shirt by the US-based custom menswear company J.Hilburn.

There’s no room for ego when getting fitted for a shirt by the US-based custom menswear company J.Hilburn.

“Please don’t suck in your stomach,” says Jon Patrick, the company’s vice president of product, as he pulls a tape measure around my waist. About 95% of the stylists at Patrick’s company are women, which he says exacerbates the honesty issue for male clients during fittings. ”When you’re being measured by a woman, you tend to stand really straight,” he says. “You suck your gut in.”

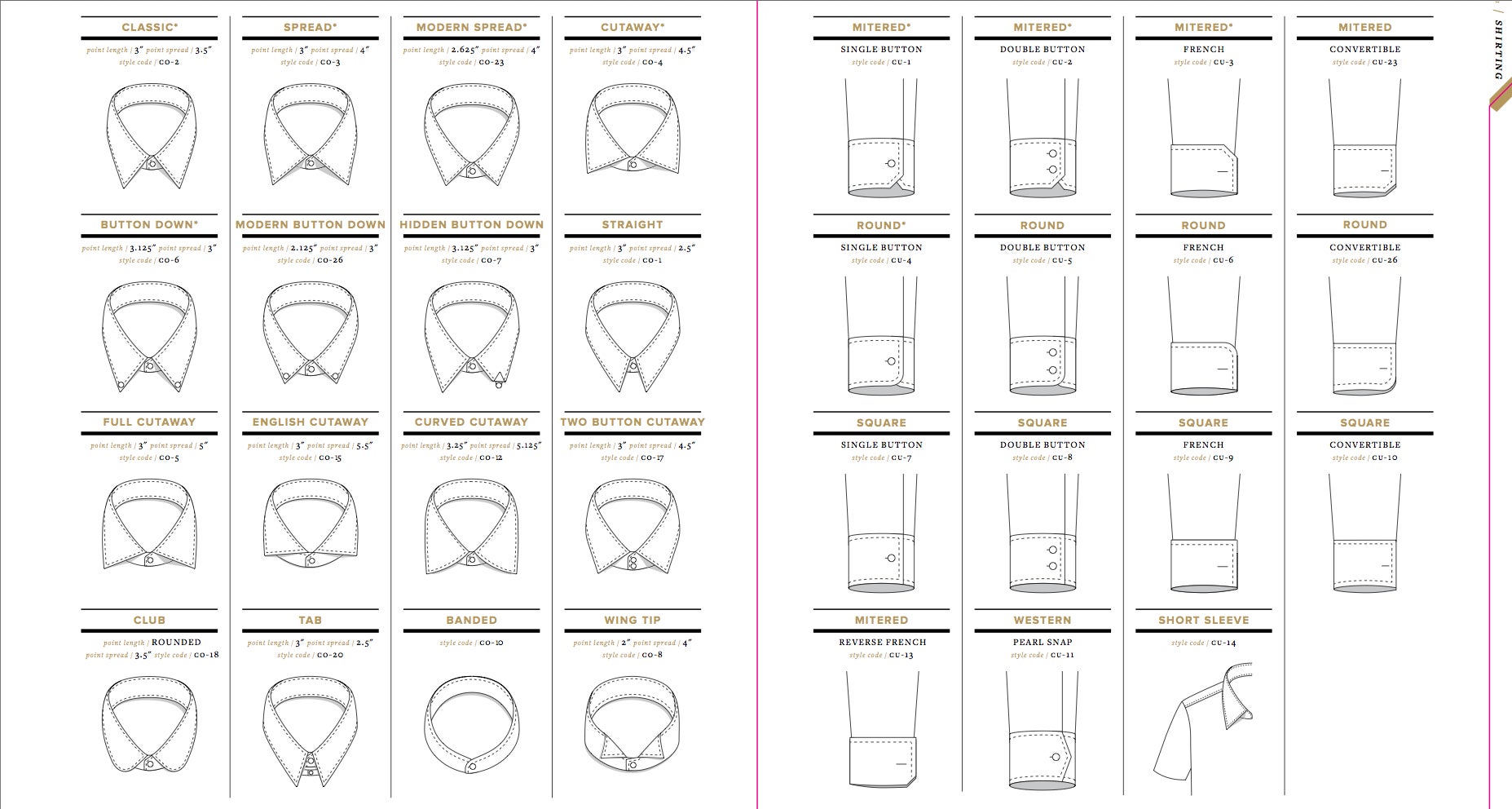

Patrick guides me through about 10 customization options for my shirt, including a selection of fabrics, collars, cuffs, pockets, and interlinings (to determine how stiff the collar is). He offers suggestions based on whether the shirt is for work or casual wear, and what I like about ones I already own. If I had ordered it—my fitting was purely for research—my custom-made shirt would have cost $99 or more, and arrived in about two weeks.

J.Hilburn is one of a growing group of North America-based online custom menswear companies. When it launched in 2007, e-bespoke was a niche market with just a few players. Today, more than a dozen companies—and counting—work on basically the same business model: letting guys buy custom-made clothing online. By outsourcing production and selling directly to customers, these companies avoid retail markups and maintain healthy margins, despite relatively modest prices. A custom shirt, for instance, can cost just $60 at some sites, and J.Hilburn boasts that for $150 it can offer a shirt made with the same high-end fabric that an Italian luxury brand would charge upwards of $600 for.

Style conscious guys have responded by opening up their wallets. J.Hilburn currently does more than $50 million in sales each year, up from $3.25 million in 2009. Indochino, which launched in Vancouver in 2007, has received $13 million in funding, and in 2012 it was reportedly doubling its annual revenue each year. Proper Cloth, established in 2008, and Blank Label, launched in 2009, both bring in upwards of $1 million in annual sales.

These companies’ fitting methods range from traditional to high-tech. Indochino invites customers to be measured in showrooms in select cities, and runs a traveling tailor program. Mail your favorite shirt to Proper Cloth, and it will knock off the fit. Blank Label uses a questionnaire about body size and fit preferences to create custom measurements. Knot Standard calculates your dimensions with the help of your computer’s webcam. Most of these brands also let you order online with measurements you take at home.

Ordering custom clothing is a habit that tends to start with shirts. ”Dress shirts, for lack of a better term, are kind of the gateway drug to the brand,” Patrick says. “Usually it’s a white or blue dress shirt. The pill that sends them over the edge is lavender. They’ll go to the office and some woman will compliment them, and they’ll come back here glowing.” Before long, says Patrick, that guy is shopping for Liberty of London’s busy floral prints.

As well as custom suiting, some brands offer bespoke casual clothes. Todd Shelton recently completed construction on its own factory in New Jersey, for making custom shirts and jeans.

The market caters generally to men who buy Brooks Brothers, rather than Dries Van Noten or Comme des Garçons—guys looking more for great fit than fashion-forward design.

“For us it’s really more about problem-solving and helping you address needs in your wardrobe,” Patrick explains.

If that’s the case, American guys must have plenty of sartorial problems, because e-bespoke companies have no shortage of customers.