The solution to Wall Street’s 1960s paperwork crisis could also save bitcoin

In the late 1960s, Wall Street had a paper problem. Every time a stock changed hands, a physical stock certificate had to be exchanged as well.

In the late 1960s, Wall Street had a paper problem. Every time a stock changed hands, a physical stock certificate had to be exchanged as well.

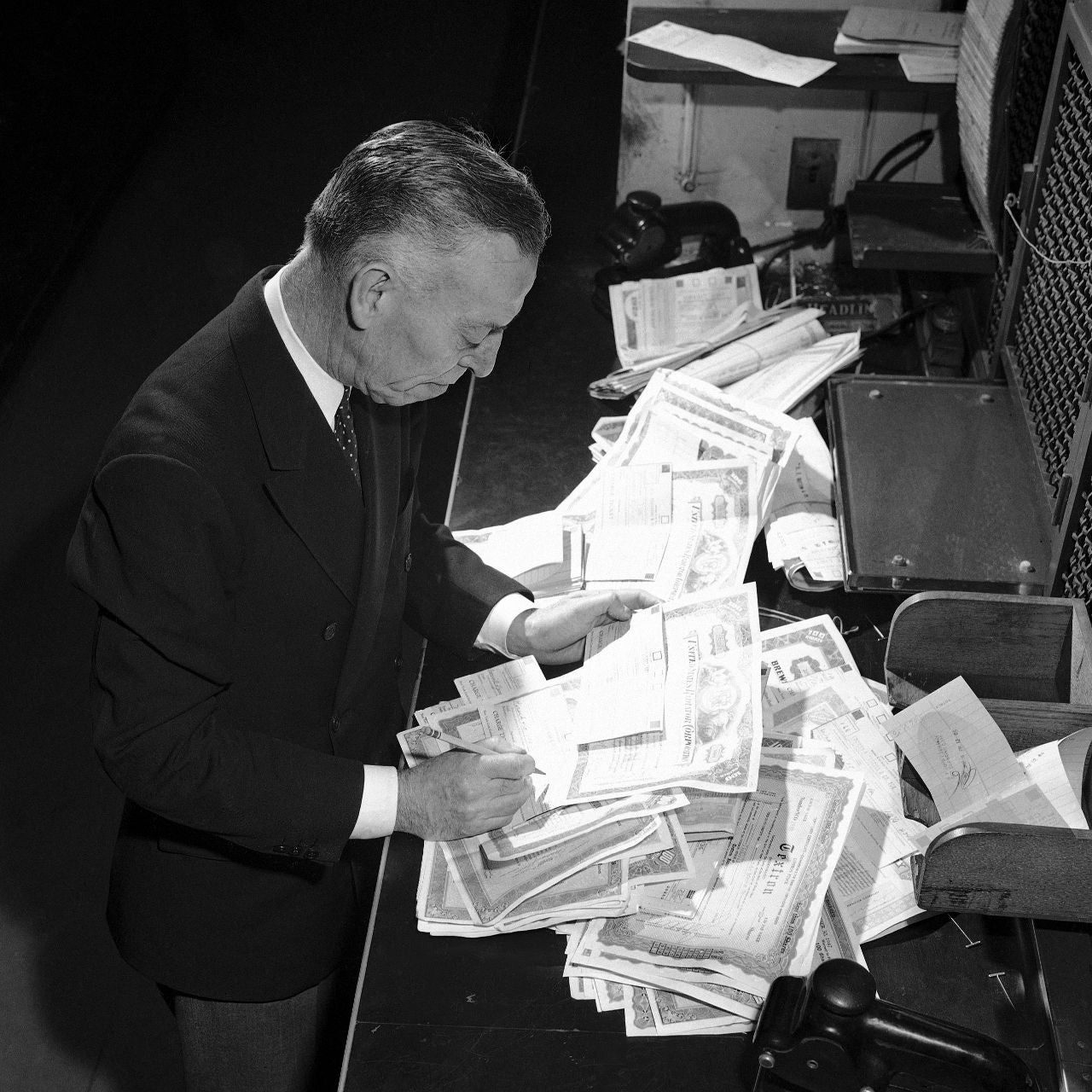

Back then, the securities business relied on a cottage industry of old men, often retired police officers and firemen, chomping cigars in trench coats as they schlepped valises, suitcases and even steamer trunks full of stock certificates—or bearer bonds, or cash—to and fro in lower Manhattan, in New York’s financial district. If a courier was out on the street with a particularly valuable suitcase, the risk manager—he was not a spreadsheet jockey, but rather the guy who managed the metal cage holding the firm’s valuable documents and cash—would ask the other couriers to sit tight until the transaction “cleared” and the other side of the trade was safely back in the bank.

The growth in stock trading in prosperous post-World War II America, and the burgeoning financial sector’s own ambitions, eventually overwhelmed exchanges and brokers. In 1969, a firm that was later folded into Merrill Lynch employed 600 people just to manage stock certificates.

The whole, paper-based system left plenty of room for mix-ups and foul play, resulting in missed trades, brokerage failures, market shutdowns, and theft. According to a New York Times report from the era, up to $400 million in lost or stolen securities were reported between 1967 and 1970—in 2015, that would be equal to $2.8 billion, adjusting for inflation. In 1967, a 22-year-old stock clerk was indicted for stealing $900,000 in IBM stock certificates—a cool $6.3 million in today’s dollars.

The RAND Corporation, a policy research group, was called in to help solve the problem. Technology seemed to be the solution. Computerized punch cards soon began to take over the exchanges. But as late as 1973, financial advice columns urged people to take delivery of their stock certificates rather than leave them “in the street,” that is, in the hands of their brokers. When brokerages failed, any investments they still held for their customers would disappear, too.

This history echoes loudly in the recent failures of bitcoin exchanges and in the lost investments of users who kept their cryptocurrency “in the street”—in this case, on the ledgers of an exchange, rather than secured in their own bitcoin wallets.

These failures, however, weren’t due to paperwork problems, since the blockchain protocol behind bitcoin builds the record of a transaction into every transaction it executes.

So does that mean we’ve reached the end of our parable about 1960s Wall Street and its parallels to bitcoin? Of course not.

Trust us

Wall Street’s big problem back then wasn’t actually solved with technological advances in bookkeeping, but with trust.

By the end of the 1960s, the New York Stock Exchange had debuted a “central stock certificate system,” to deliver securities electronically. It was rudimentary, voluntary, and unreliable, but it formed the basis for the major breakthrough that would come in 1973: the creation of the Depository Trust Corporation. As its name indicated, the DTC required that all the players in the market rely on a single, centralized institution to hold, in 1973, 1.5 billion shares worth $55 billion.

Bitcoin, in contrast, is famously designed to be a “trust-less” payments system (pdf). It relies on an electronic ledger and a deliberately decentralized accounting system, giving users the ability to transact quickly, without intimate knowledge of the person on the other side of the exchange.

That hasn’t prevented a problem that plagued the paper-based Wall Street of yore: competing claims on ownership. As the Financial Times noted this week:

Indeed, given the high volume of fraud and default in the bitcoin network, chances are most bitcoins have competing claims over them by now. Put another way, there are probably more people with legitimate claims over bitcoins than there are bitcoins. And if they can prove the trail, they can make a legal case for reclamation.

This has George Fogg, a lawyer with Perkins Coie who is cited in the FT piece, thinking about bitcoin’s relatively ambiguous treatment under the United States’ Uniform Commercial Code, and the role that a trusted intermediary might play. And as Fogg told the FT, the precedent for this dates back to Wall Street’s shift from delivery of paper stock certificates to centralized clearing.

There are a limited number of bitcoin in circulation, and a not-trivial amount has been exchanged in disputed transactions, whether robbed from troubled exchanges or seized by the government. Nonetheless, bitcoin users generally are not enthusiastic about that kind of centralization Fogg is suggesting.

Nothing new under the sun

Watching the bitcoin market develop, you get an appreciation for why other financial systems developed the way they did.

Companies that help you buy bitcoin, hold it, and transact it: you might call them brokerages, or even banks. Deposit insurance? Bitcoin doesn’t have it yet, but there’s a clamoring for it every time an exchange fails and its customers are left with no recourse for their vanished wealth. And while bitcoin was designed to function without a central bank, the currency’s price volatility has some bankers recommending the creation of one.

And now here we are, half a dozen years into bitcoin’s existence, talking about the potential value of centralized clearing.

It’s not criticism to say that the bitcoin financial system will likely adopt a number of the features of the current one—merely a reminder that those features tend to exist for good reason.