Cotton, the other globally glutted commodity

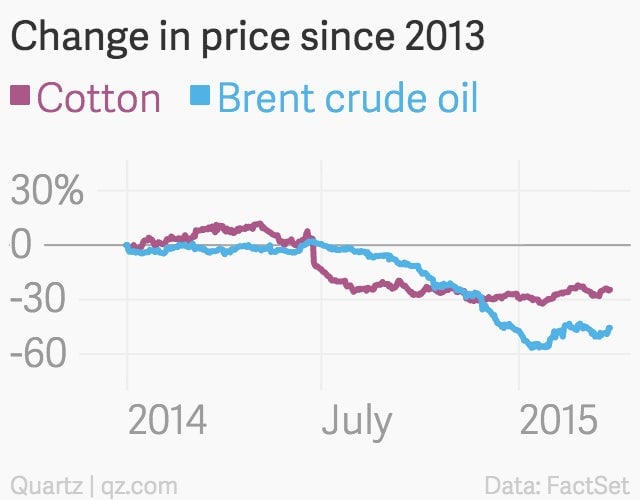

The price of a given commodity is falling, rapidly. A key market has way more of the stuff than it used to. Producers are panicking and trying to shift resources to avoid selling into the glut—not to mention the strong US dollar is making it harder for manufacturers around the world to import what they need.

The price of a given commodity is falling, rapidly. A key market has way more of the stuff than it used to. Producers are panicking and trying to shift resources to avoid selling into the glut—not to mention the strong US dollar is making it harder for manufacturers around the world to import what they need.

That’s a scenario that has been playing out a lot recently, as a global economic slowdown (paywall) makes it harder for countries around the world absorb all the natural resources getting plucked and mined from the earth.

One of the latest examples: cotton. And the key market stuffed to the brim with it? China.

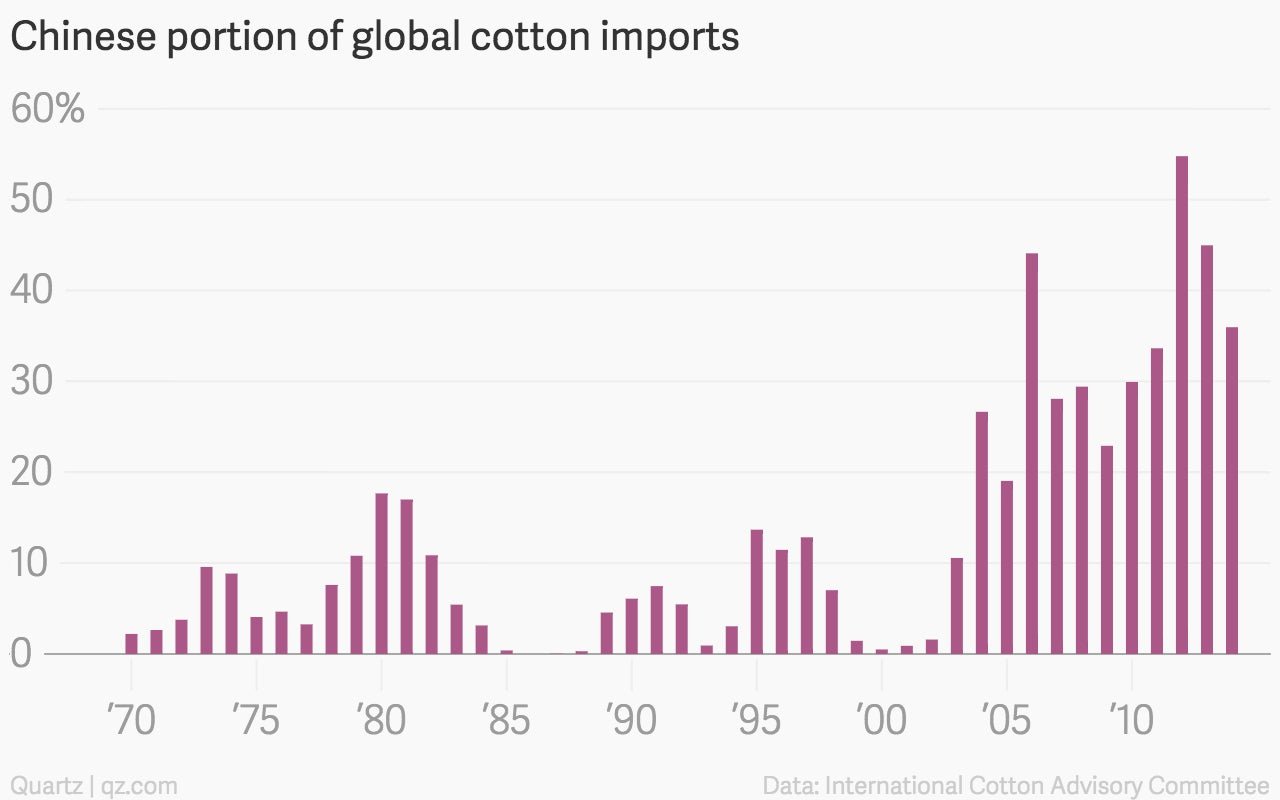

“The international cotton market is really driven by China,” says Victoria Crandall, a commodities analyst for Togo-based Ecobank. “It’s the largest producer and it’s also the largest buyer.” (But it won’t be the largest producer for long; India is expected to overtake the rankings by next year.)

In 2012, China accounted for more than half of global cotton imports, according to the International Cotton Advisory Committee. Last year it took in barely more than a third. And the ICAC is expecting that number to shrink further this year.

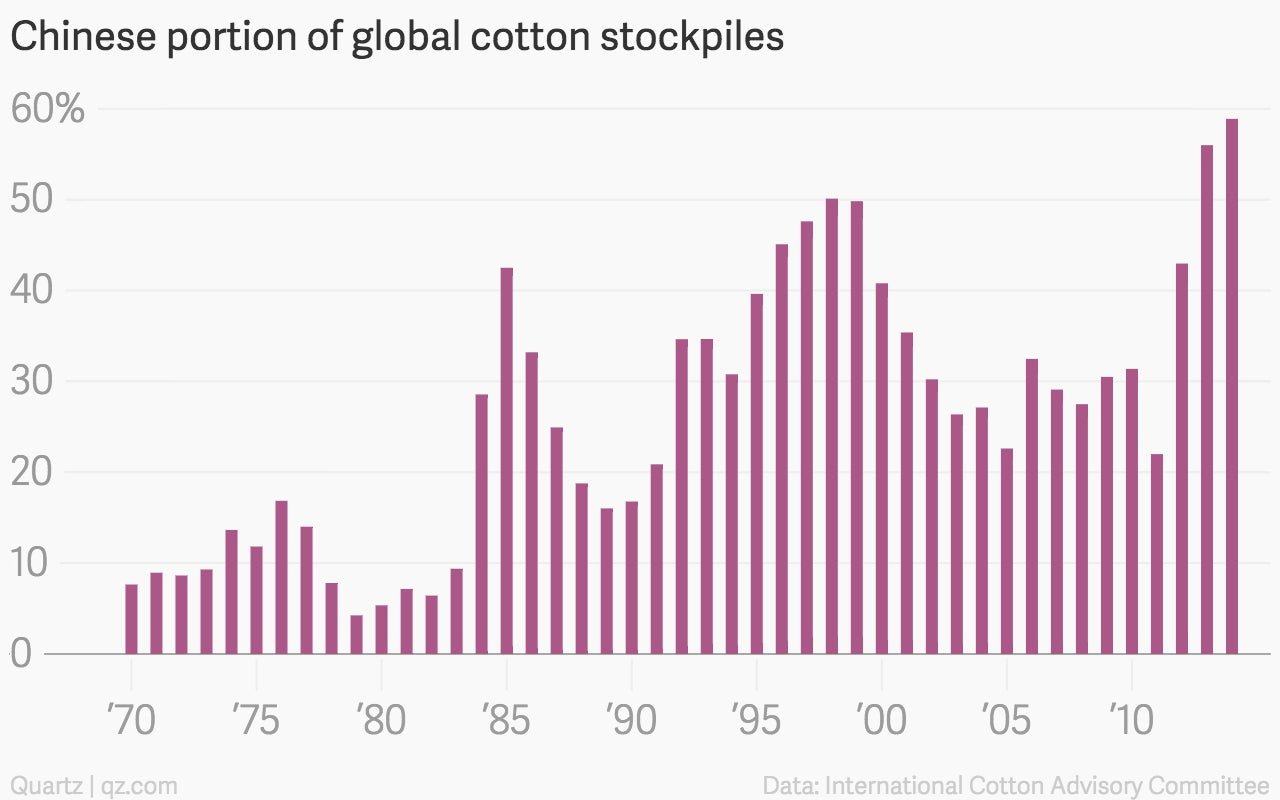

But those imports weren’t all going to textile factories and domestic consumers. No, China was stuffing it in warehouses as part of a strategic reserve it started in 2011 to support Chinese farmers.

“They use it as a tool against US exports,” says Avery Putter of commodities broker Sweet Futures. The US (which has its own protectionist cotton policies) is the world’s biggest cotton exporter.

As China’s cotton supplies exploded, so did its portion of the global cotton stock.

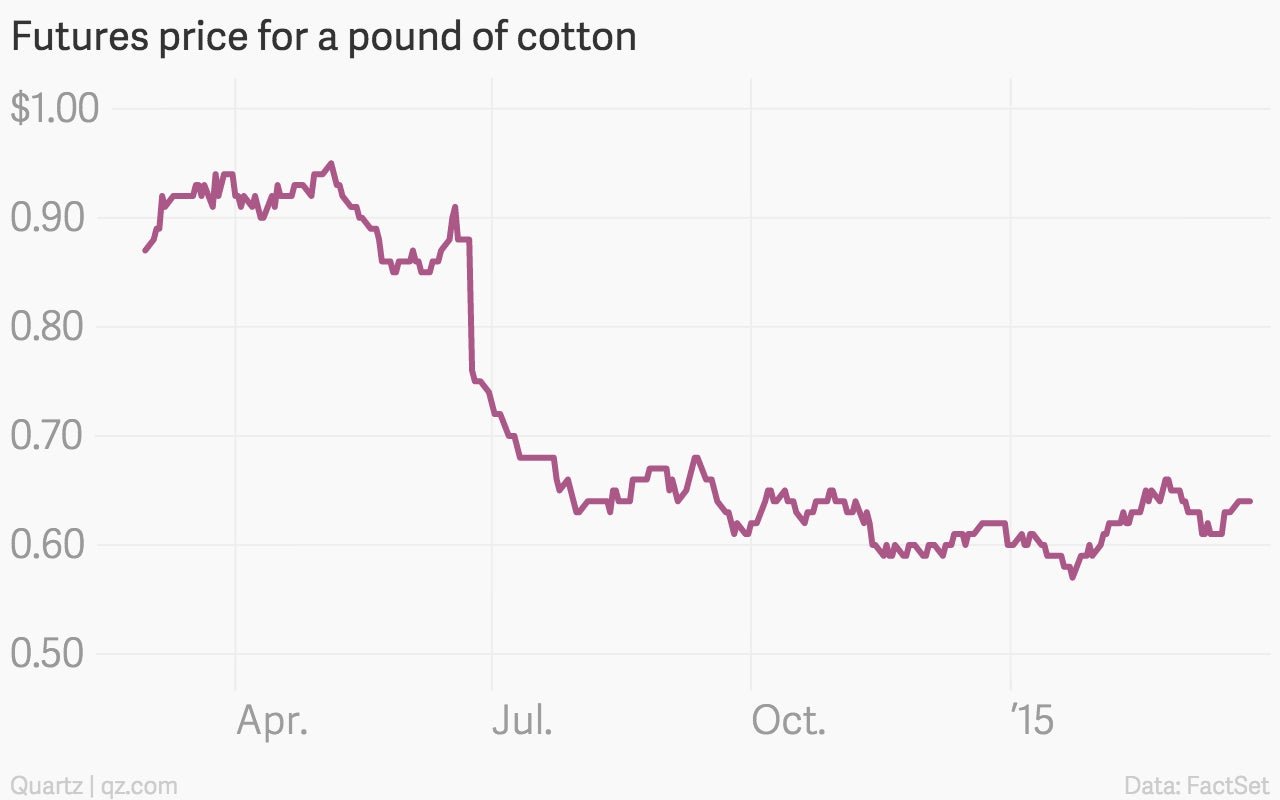

But China ended its cotton reserve policy (paywall) last year, so now that cotton is flooding back into the market, crushing prices.

“China’s trying to flush out these stocks as fast as it can,” Crandall says.

As the market seeks its equilibrium, the rest of the world is consuming a bit more cotton and—more importantly—planters are easing up on production. That shows up in the the ICAC stats, with demand now forecast to outstrip supply next year. But it’s showing up anecdotally, too. Agricultural chemicals company FMC saw one segment’s sales fall 7% last quarter, which it blamed on the cotton slump. “This performance was primarily due to slower demand in Brazil, specifically delayed planting and lower cotton acreage reduced insecticide and herbicide volumes,” CEO Pierre Brondeau told investors during the company’s most recent earnings call.

But the reduced planting might not be enough to prop up cotton prices. Besides China’s huge stockpile lingering in the background, cotton competes with synthetic fibers like polyester, which are also getting cheaper because of lower oil prices.

“Moreover, as technology has improved the texture and durability of man-made fibres, cotton’s share of the fibre market has fallen to 29%, from 36% ten years ago, a trend we expect to continue,” commodities economist Hamish Smith wrote in a note for Capital Economics clients earlier this month.

You might think that all this cheap cotton is having an impact on clothing prices. It isn’t! Like most firms with large commodity needs, clothing manufacturers hedge their purchases so far in advance that sudden price drops don’t show up instantly, or as dramatically as you’d think. Here’s how H&M’s head of investor relations broke it down during a February earnings call:

Okay, let us start with the cotton then. It’s true that cotton prices, spot prices, have been decreasing last six months or so, but we don’t buy cotton as such. We design products, we have them produced, and it’s more about the prices or cost on fabrics, and of course it’s much more than just cotton that goes into a fabric—there are chemicals and other materials, etc. And all in all, the prices of fabrics have not decreased as much as the cotton prices. So it’s—yes, it’s a decrease, but not materially.