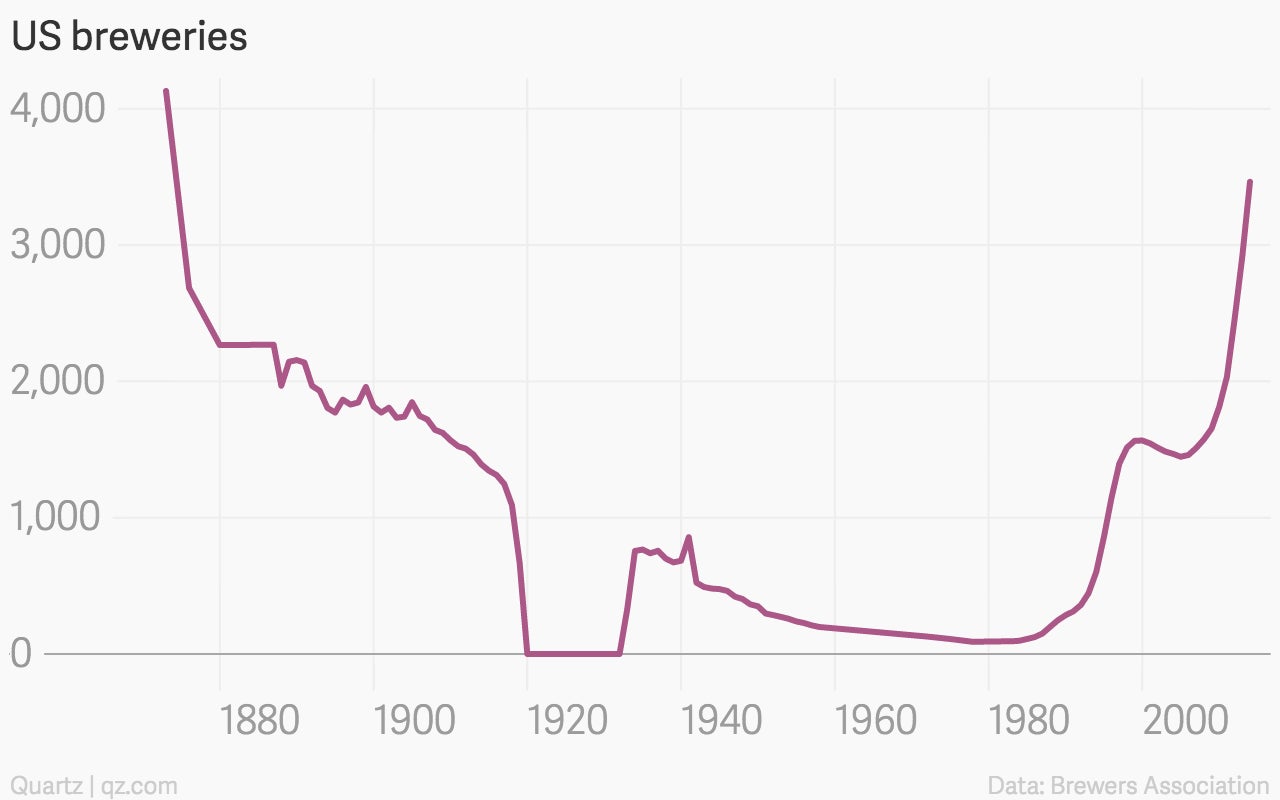

The birth, death and resurrection of American beer: 1873-2014

Mass-produced beer wasn’t always America’s brew of choice.

Mass-produced beer wasn’t always America’s brew of choice.

Hard cider was the preferred North American beverage in the early years of the nation. (Founding father President John Adams was famously said to knock back a tankard of cider at breakfast each day.) Some drank ales and porters, traditionally British brews. But their heavier alcohol content and uneven quality made them something of a niche product.

In fact, beer as Americans know it—a lighter, lager-style beverage—didn’t burst on the scene in until the 19th century, thanks to surging German immigration to the US. In the three decades after the US civil war, which ended in 1865, a growing population and an influx of beer-drinking immigrants sent per capita consumption of beer up 340%, to 15 gallons a year in 1895.

Initially, regional and local breweries met most of this demand. But increasingly a crop of German-American beer barons took advantage of new technology such as refrigeration, pasteurization, mechanized bottling and national railroad networks to dramatically boost production and distribution. Over time these famous brewing families—Pabst, Busch and Schlitz among them—elbowed aside the smaller regional breweries.

America’s experiment with the prohibition of all alcohol sales in the 1920s literally stopped industrialized brewing in its tracks. (Large breweries such as Anheuser-Busch managed to survive by selling products for home brewing—such as malt and yeast—which was still allowed and understandably surged in popularity during the period.) After prohibition large national breweries rapidly returned to dominance, as the number of US breweries continued to decline before reaching a nadir in the late 1970s.

That industrialization of the US brewing industry has long been held up as a model of US management savvy and expertise in exploiting economies of scale. But over time, big beer’s strength—an unparalleled ability to ship standardized, consistent product throughout a vast distribution network—has become its liability. Starting in the 1980s, the number of US breweries began a sharp rise, driven by increasing demand for craft beers.

The rise of craft beer reflects the fact that consumers in developed market economies are increasingly opting for higher-priced smaller, regional, and organic offerings, and that’s prompting food and beverage giants around the world to rethink their approach to their traditional products. Anheuser-Busch’s parent conglomerate AB InBev has recently been snapping up smaller craft breweries such as Seattle’s Elysian Brewing, Chicago’s Goose Island, and Long Island’s Blue Point, in order to cater to this market. Other beer giants have ginned up craft-like brews of their own, that are careful to de-emphasize—or just hide—the beverage’s corporate parentage. SAB Miller’s Blue Moon is an example of that strategy in action.

While it’s unclear whether their newfound attention to craft beer will offset weakness in the beer giants’ core lager business over the long term, this attention to consumer habits in the US has worked well recently, amid a slowdown in emerging markets such as China and Russia over the last year.