It’s looking increasingly likely that the Obama administration will not reach a deal with the Republicans who dominate the US House of Representatives before Jan. 1, triggering the automatic tax hikes and spending cuts known as the “fiscal cliff.”

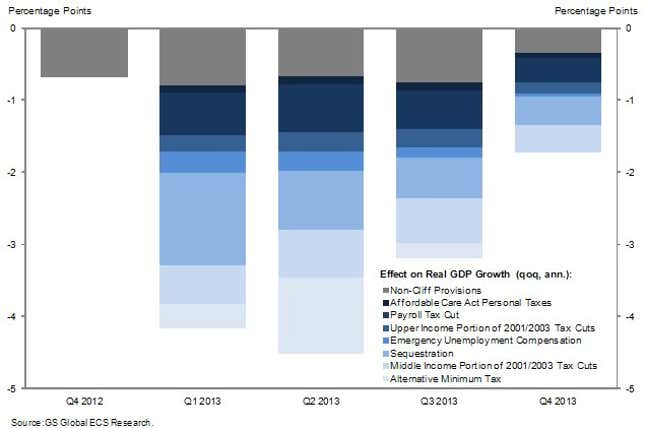

As several commentators have pointed out, the cliff is really more of a slope. It’s true that by the end of 2013 it could slash GDP growth by 4%-5% as the government saps some $600 billion from the private sector and households (see chart below). But—and this is why the administration seems pretty relaxed about letting the deadline expire—most of the potential impact won’t happen on Jan. 1.

Nor during the rest of January, for that matter. Nearly all of the tax increases will take effect gradually. And though the president will direct agencies to implement ”sequestration” (i.e., spending cuts) on Jan. 2, the Office of Management and Budget has plenty in its bag of tricks to forestall the cuts. In fact, government agencies have reacted hardly at all to the new inevitability of cliff-diving. At least during January, going over the cliff will have all the observable impact of, say, the Mayan apocalypse.

Still, the impact will build, slowly but steadily, as the month wears on. If there’s still no deal by February, the outlook will be much darker. Here’s a rundown of what might happen from now until the end of January:

- When they reopen Wednesday, markets, already increasingly volatile, will begin to show more pronounced signs of jitters. As Time reports in an excellent interactive chart, a recent Bank of America survey of money managers suggests that markets had not yet priced in the impact of the fiscal cliff. Plus, the impasse in the House now makes it clear a swift consensus after Jan. 1 won’t be easy.

- While markets may adjust to the expectation of a delayed deal in the week before New Year, Jan. 2 will almost certainly see pessimism punish equities, setting off a chain reaction in the rest of the world’s markets. A flight to safety could drive even more money into Treasurys as well.

- On Jan. 1, physicians will begin to see a 27% drop in Medicare reimbursement payments due to the expiry of an annually negotiated provision known as the “doc fix”. At minimum, this could mean that fewer physicians accept Medicare (i.e., elderly) patients.

- On Jan. 7, 2.1 million Americans who had been eligible for an extended period of unemployment insurance, which averages out to about $284 a week, will stop getting it. (The Washington Post reports that another 1 million will see their unemployment checks slashed in April.) That loss of income will contribute to the gradual cave-in of consumer demand.

- A still bigger blow to demand comes on January 15, when working Americans will start losing an extra 2% from their paychecks as the Social Security payroll tax cut expires. Those earning more than $250,000 will also pay new taxes associated with Obama’s health care reform.

- Technically, the Bush tax cuts expire on Jan. 1, raising most people’s federal income tax rate by several percentage points. They’re unlikely to be felt all at once: the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which each year tells employers how much tax to withhold from paychecks, hasn’t yet issued a withholding schedule for 2013, because it’s expecting that a deal will prolong at least some of the tax cuts. If negotiations drag on, the IRS will eventually have to act, and the higher taxes will start to bite—another knock to demand. However, at some point in January, absent a comprehensive deal, the House will be compelled to pass a stopgap bill making the expired Bush tax cuts permanent for those making more than $250,000 (the Senate has already passed something similar, and the measure is popular with the public). Such a measure would also limit the fiscal cliff’s impact by stopping the defense-related sequestration cuts, predicts Ezra Klein.

- While reinstating the Bust tax cuts for all but the wealthy is the bare minimum that the American public can expect in January, it can be confident about a bargain on little else. Whether a small-scale deal that Klein thinks is likely would revive stocks and unwind money from Treasurys will depend in large part on whether the two sides agree on a timeframe for signing a broader package. If a stopgap deal extending the Bush tax cuts and preventing defense cuts is the most that occurs in January, other government departments will need to begin making more serious attempts to slash their spending toward the end of the month and the beginning of February. These cuts will compound the drag on demand, nudging the economy into a recession, most likely toward the end of Q1.

The macroeconomic impact

If January comes and goes without a comprehensive deal, the above changes will have leached off only about 0.85% of GDP growth, based on estimates from T. Rowe Price.

However, as sequestration cuts and tax withholdings began whirring into motion in February, growth will contract more dramatically. With no deal by the start of February, the US is also likely to run up against its debt ceiling again—another item that the fiscal cliff negotiations were supposed to resolve—although the timing depends on whether a stopgap deal replenishes government coffers and on how fast sequestration takes effect.

Another showdown on the debt ceiling could prompt a sovereign-debt downgrade by Fitch Ratings, echoing last year’s downgrade by Standard & Poor’s. Ironically, this will likely drive more money into US sovereign debt instead of less, as investors sell off equities and other risky assets and rush to the safety of US Treasurys. The irony is, however, also telling: since the fiscal cliff’s effect would be to sharply tighten government finances, it would quell paranoia about the US’s debt-to-GDP ratio, even as a recession starts to take hold. That might be grim tidings for corporate earnings and US households, but it’s good news for deficit-phobes. And, in a way, they might be right—after months of being compared to that of Greece, the American economy will finally have set off down the path of euro-style austerity.