How the rise of digital banking might set back a US civil-rights law

The rise of internet banking is making itself felt in an unexpected area: American civil-rights law.

The rise of internet banking is making itself felt in an unexpected area: American civil-rights law.

Before the financial crisis, bank branches in the US multiplied like Starbucks locations. Now they’re dwindling like Radioshacks. During the boom, banks largely excluded minority and working-class communities from new branch openings. Since then, they’ve been targeting them first for branch closures, as a means of cutting costs amid falling foot traffic.

Enacted in 1977, the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) was a federal response to decades of redlining—a type of racial and economic segregation best known for a legacy of denying mortgages to black people—and a tool to discourage banks from such unfairness. It penalizes banks that don’t provide certain levels of service to low-income communities.

But with the increasing popularity of mobile and online banking, regulators have proposed an update to the CRA that would give less weight to physical branches. This is despite concerns that doing so will perpetuate discrimination against minorities and the poor—as well as letting banks off the hook for decades of such discrimination in the past.

“There ought to be some caution,” said Bob Dickerson, board chairman of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC), which opposes the shift (pdf). “Our communities need banks that have a physical presence as well as an online presence.”

The limited powers of bank regulation

A key provision of the CRA, the “service test,” gauges how much banks are serving their communities. How many branches a bank has in lower-income areas weighs heavily in the determination of whether it passes or fails that test. If it fails the service test and other parts of the CRA examination, then regulators have more power to block expansions or mergers.

Under the proposed rule change (pdf, p.3), the distribution of bank branches would still be a factor in the service test, but would no longer be the “primary emphasis.” Gaining greater weight would be “alternative” systems like ATMs and digital banking. The proposed rewording was submitted in September and the comment period ended months ago, but regulators haven’t come out with a final rule yet.

Dickerson, the NCRC chairman, got his start in banking in the late 1970s in Mississippi and Alabama, and he remembers that bank branches weren’t equal in distribution or even quality. (“This is a 30-year problem,” he told Quartz.) When he worked for Deposit Guaranty Bank, a predecessor of today’s Regions Bank, in Jackson, Mississippi, the differences were stark. The downtown branch, close to the city’s commercial center, was far nicer than the one he worked at in a poorer, blacker neighborhood. “My branch was so small that when my secretary was getting ready to get up, her chair bumped my desk,” he said.

Though the CRA is explicitly about economic discrimination, not racial discrimination, the government has used the law to prosecute banks for explicitly racial discrimination in the past. In 1994, the Justice Department settled charges with Virginia’s Chevy Chase Bank because it didn’t market to customers or open branches in Washington DC’s black neighborhoods, despite them being included in its CRA service area.

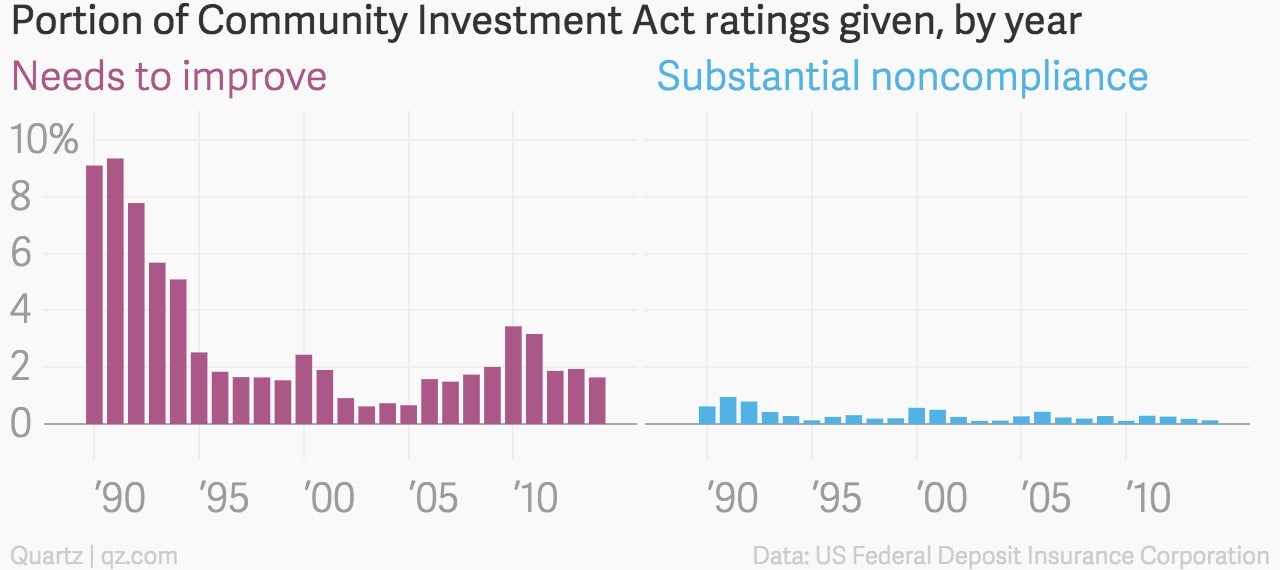

But banks seem to get in a lot less trouble under the law than they used to. For most banks, there are four possible CRA ratings: “outstanding,” “satisfactory,” “needs improvement,” and “substantial noncompliance” (large banks get a high or low satisfactory rating). The bottom two ratings can have problems when they want to expand or merge, though fewer and fewer banks are receiving them these days.

On its face, this suggests banks are actually getting better. But some critics of the CRA say (paywall) that it encourages “tokenistic” compliance with the rules, rather than demonstrable improvements in the availability of credit or banking services in lower-income communities.

What’s certainly true is that the CRA’s powers are limited. It can put pressure on banks with plans to expand, such as BBVA Compass, the last high-profile bank to fall foul of the CRA, which promised $11 billion in loans and development funds to poorer communities after getting a ”needs to improve” rating last year. But the consequences of a low rating are less clear for banks that have no ambition to add branches or merge with another institution.

Reynolds State Bank, a small lender in Reynolds, Illinois, for example, has received seven “substantial noncompliance” ratings in a row since 2006, with no discernible impact on its operations, though it has recently launched a website and is planning a mobile banking app. “We regard it as significant and important and we’re trying to correct it,” a representative from the bank told Quartz regarding its CRA ratings.

In this context, opponents of changing the CRA argue that it’s too weak already. “I don’t think that the regulators are tough enough, nor is there a penalty for not complying,” Dickerson said.

The hidden downside of the mobile revolution

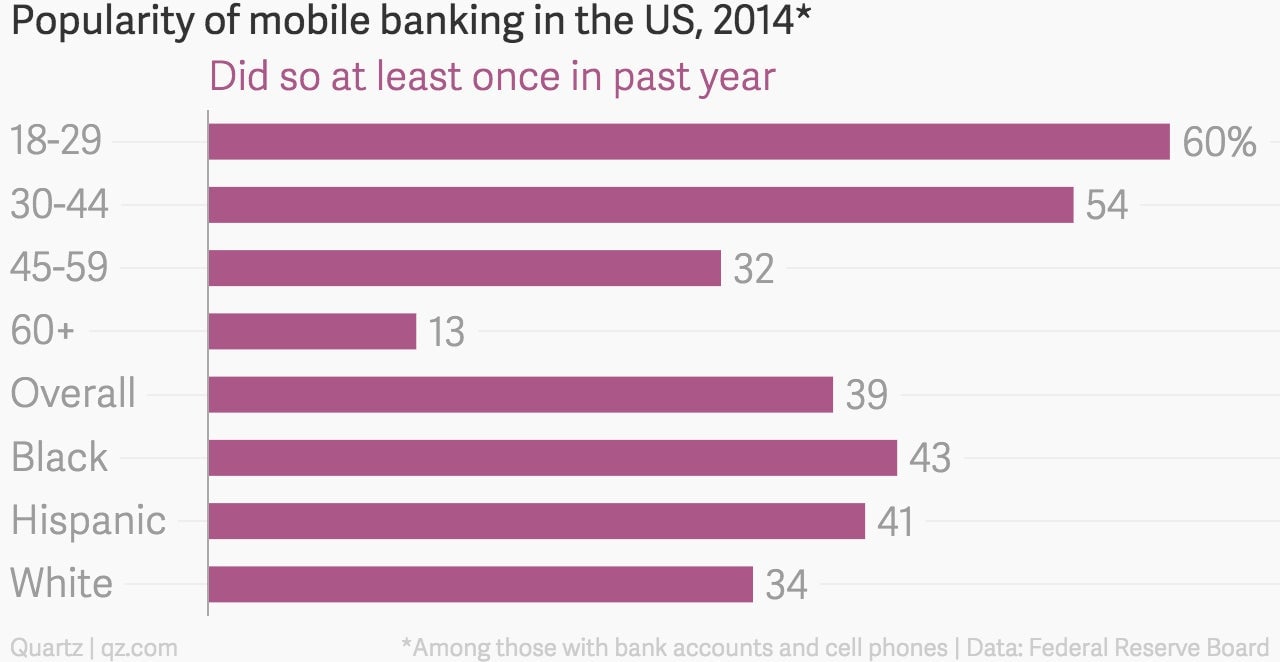

On its face, a change to bring the CRA in line with modern technology makes sense. For example, among Americans who have bank accounts, both young people and people of color are more likely to use mobile banking than their older or whiter peers, according to the Federal Reserve (pdf, p. 12).

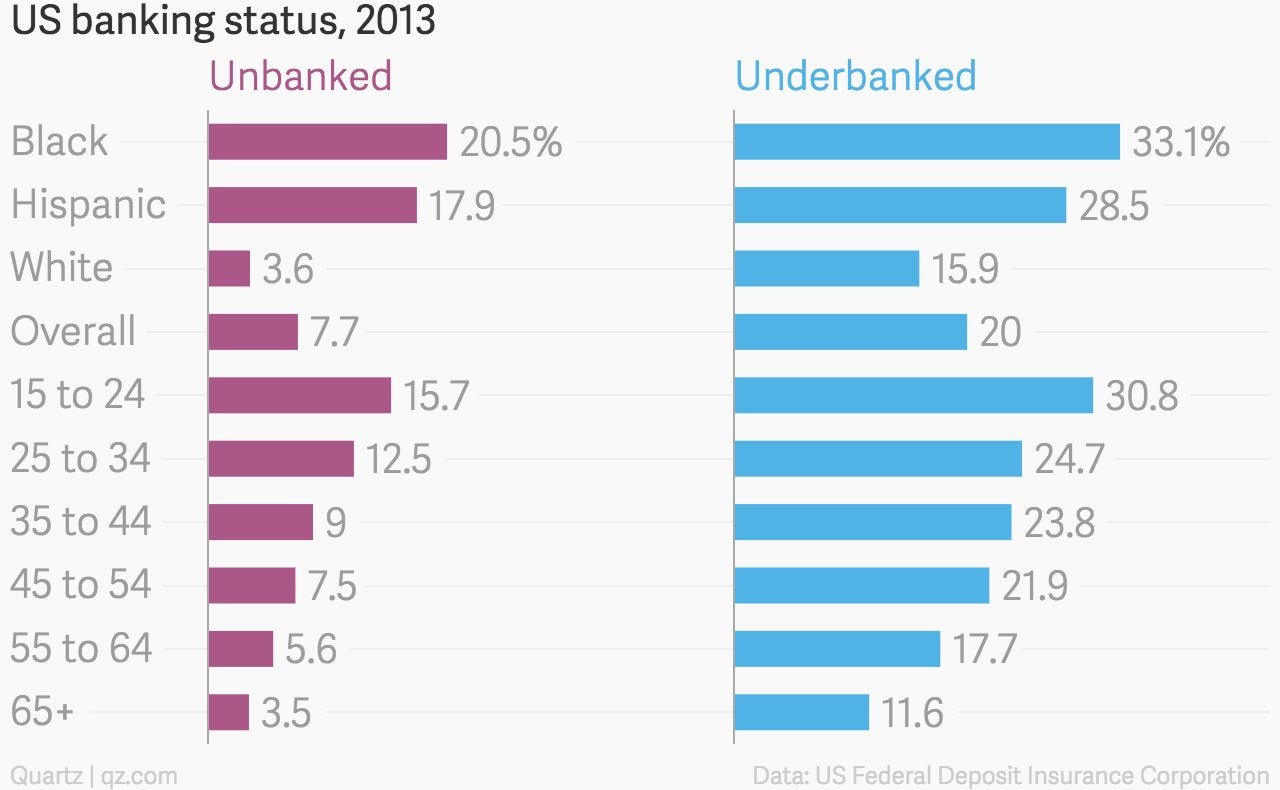

That seems heartening at first sight, since the young and people of color are more likely to be missing from the mainstream financial system in the first place. They’re likelier to be either unbanked (have no bank account) or underbanked (have a bank account but still use alternative financial services like money orders, check cashers, and payday loans), according to a 2013 survey (pdf, p. 16) by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

However, these statistics conceal a problem. A big reason that the young and people of color are more likely to use mobile banking is that they’re more likely to own a smartphone (according to a recent Pew Research Center study on smartphone use). And that’s partly because their phones are more likely to be their only way to get onto the internet.

With lower incomes on average, these groups are also a lot more likely than their older, whiter peers to run into data caps, or suspend or cancel their phone plans because they were too expensive, the Pew study found. If they don’t have a bank branch nearby, that leaves them without a way to access their accounts—and with yet another obstacle to being part of the mainstream financial system.

Why bank branches still matter

So the central question with the CRA shuffle is: Do bank branches matter if some of the people who weren’t being served by banks before are finding ways to connect with them with using newer, digital methods?

The answer: It depends.

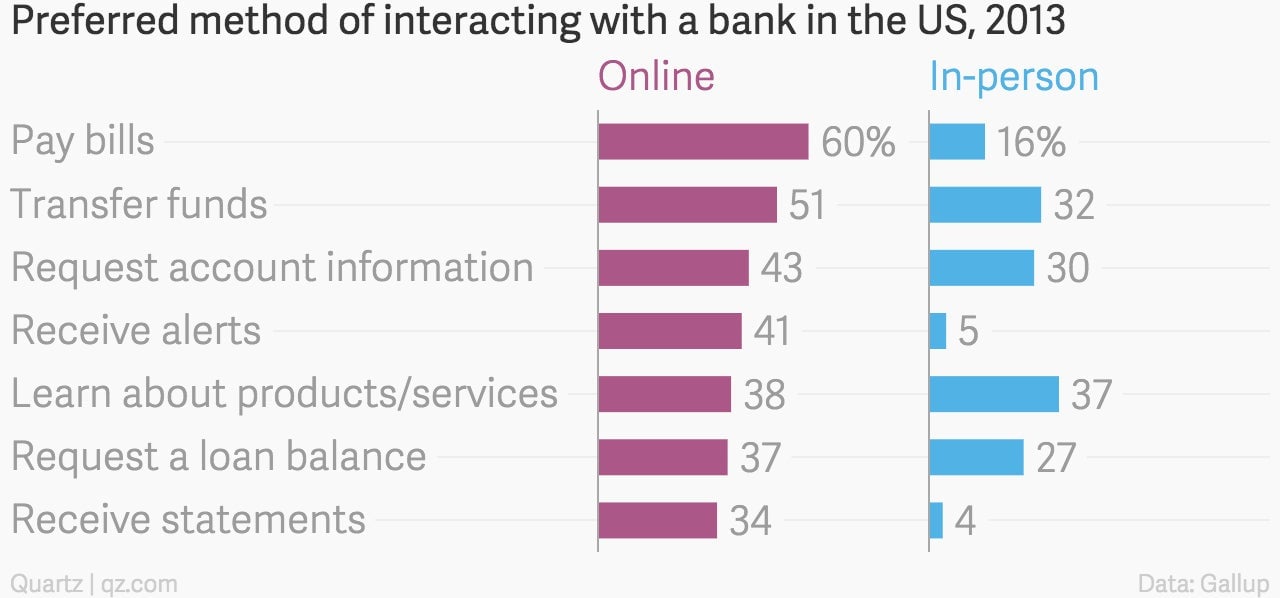

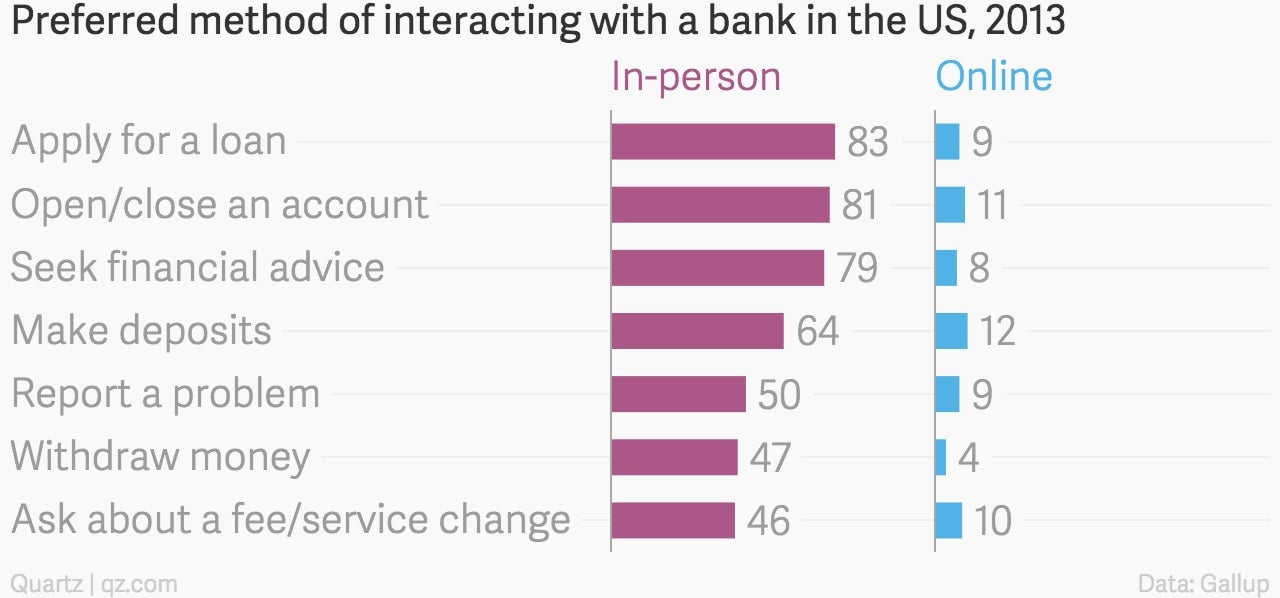

On the one hand, mobile and online banking are very good for giving people access to everyday bank stuff. A Gallup poll in 2013 showed people were more than happy to do a lot of the run-of-the-mill interactions online.

For example, Hope Credit Union in Jackson, Mississippi, which mainly serves low-income, minority, and rural communities, debuted a mobile app for its members in 2012. (Credit unions are different from banks in that they are not-for-profit, offer a different deposit insurance structure, and typically serve a far narrower customer base, but they’re still essentially in the same business of taking deposits and making loans.) Ed Sivak, Hope’s chief spokesman and policy director, told Quartz that the app has been catching on quickly with its members.

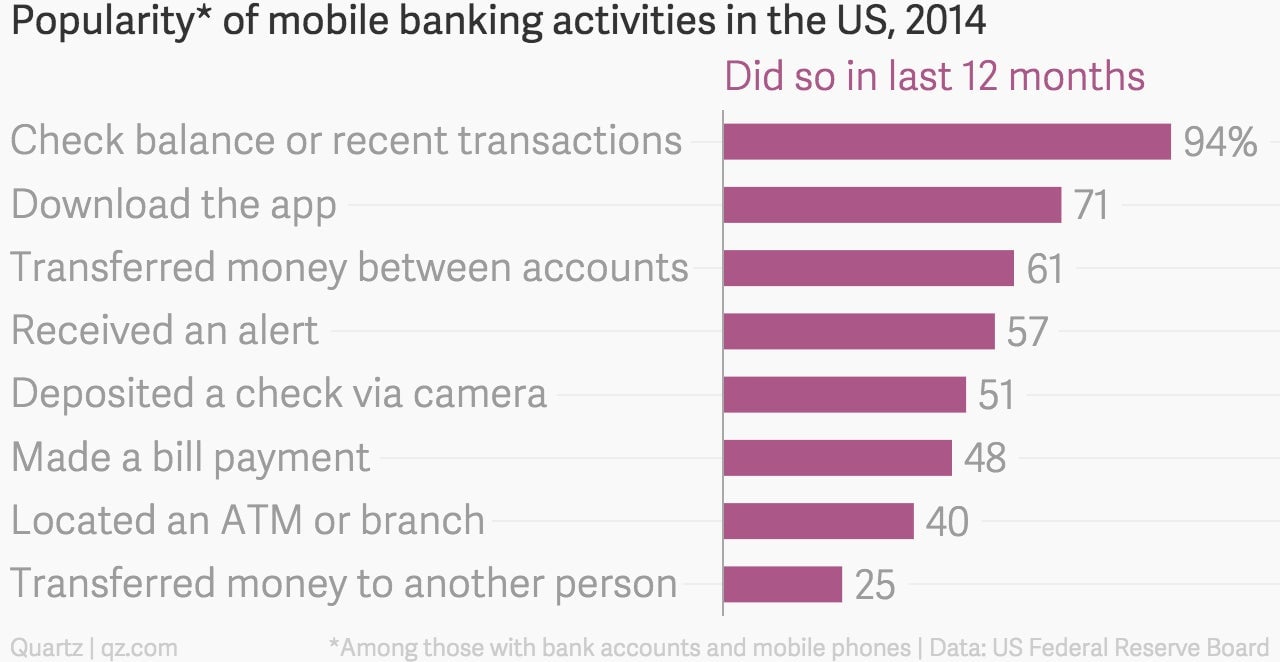

“The mobile app is really important, he said. “It’s a financial education tool.” The most popular feature is the one that lets users check their balances, he said. The Fed’s findings agree:

Many banks therefore think the revised CRA should give them credit for reaching the underbanked via mobile apps and online banking.

“Given the speed at which technological changes are altering how consumers bank, we strongly agree that consideration for newer delivery channels—especially digital channels—should receive greater consideration in the CRA evaluation,” wrote Capital One (pdf) in a letter to regulators. The American Bankers Association (pdf) and JPMorgan Chase (pdf) had similar views.

But you can only do so much on your phone. That same Gallup poll showed that Americans like going into a branch for big-ticket items, like opening accounts and applying for loans.

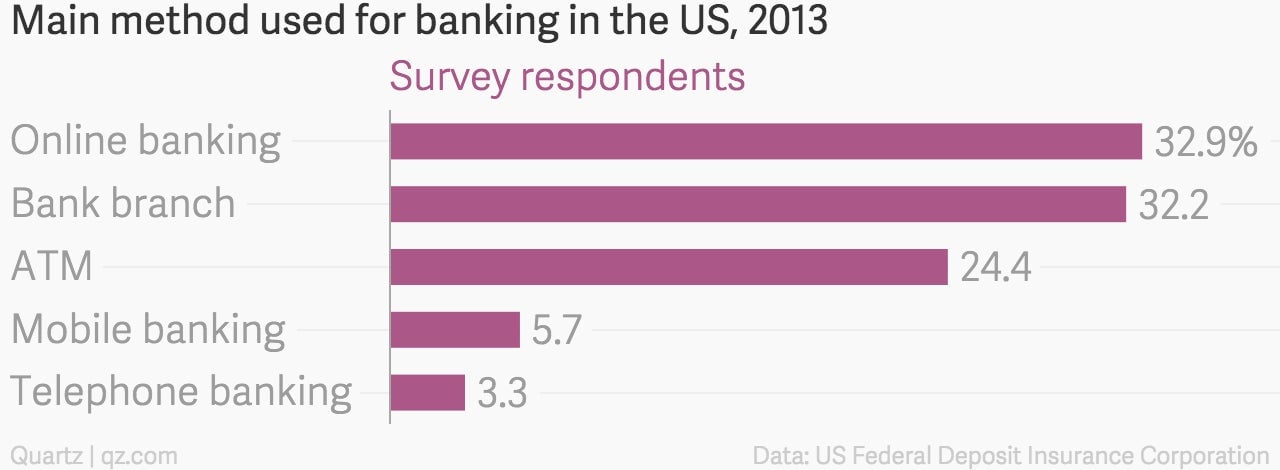

Another survey, by the FDIC, found that overall, online banking is just barely more popular than branches as people’s main means of interaction with their bank. And mobile banking trails far behind.

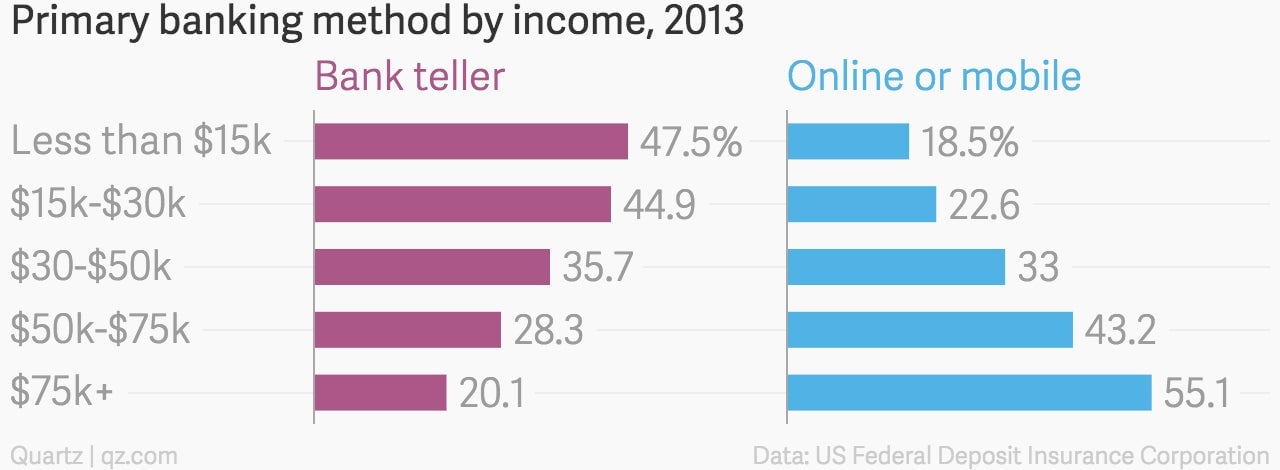

Moreover, the FDIC found, the less money people make, the likelier they are to use a branch and less likely to use online or mobile banking.

A problem of trust

There are also more structural reasons that a bank branch is important. In a 2011 commentary, researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland asked “Do bank branches matter anymore?” Their work focused on how lending decisions get made. They found that in the mortgage market, bond investors and market data more heavily influence who gets credit. But in consumer and business lending in poor and minority communities, a bank’s physical presence plays a bigger role. The intangible bits of knowledge that come out of dealing with a given population day in and day out go a long way for marginal customers, who might otherwise get weeded out with an algorithm.

A paper out of MIT’s economics department last year explored the issue further. It found that when banks merged, consolidated branches, and dropped parts of their combined loan portfolios, those same underbanked neighborhoods often had a harder time getting loans because of those lost relationships.

Last but certainly not least, a bank branch is a marker of a neighborhood’s perceived commercial and existential value. In a 2013 NPR piece on so-called “bank deserts,” Catherine Crosby of Dayton, Ohio’s Human Relations Council traced an arc of disinvestment on the city’s west side that concluded with a PNC Bank branch closing up shop: ”So we had our jobs leave and so then we had our grocery store leave and now we had our bank leave.”

Jeanne Hogarth, a vice president for policy at the Center for Financial Services Innovation, said the banks’ lack of branches in areas where the unbanked live changes the way that people interact with them. “Banks are not a presence in these communities,” she told Quartz. “People don’t grow up going to the bank every week. Mom and dad don’t have bank accounts.”

In addition, overdraft fees, minimum balance fees, and risk management tools like ChexSystems—which block “problem” customers from opening new accounts—foment a distrust in low-income households. This makes it harder to get people back into a branch, if there is one in the first place.

When people from poor backgrounds or minorities say why they prefer mobile banking, Hogarth says, “there is one reason that keeps coming up in the top three reasons: I don’t like working with banks.”

And Sivak, the policy head from Hope, said that despite their growing popularity, smartphones and computer screens won’t be enough to bridge that divide. Most Hope members still come to a branch to conduct business. “I think it would be hard to establish the trust that a community needs simply through a mobile interface,” he said.

Don’t get carried away

The FDIC, in a report last year (pdf), asked how much mobile and online banking could do to bring the unbanked and underbanked into the financial system. There was lots to be optimistic about: Digital banking already has created more access, easier access, and faster access to basic financial services. But the report also recognized the technology’s limitations.

“Relying exclusively on a mobile device for a relationship with a bank is unlikely to fully achieve the economic inclusion objectives of fostering financial empowerment, growing banking relationships, and fulfilling financial goals,” it read. “Instead, other delivery channels, particularly human interaction, are likely to be important for providing consumers the support and guidance they need.”

Mobile and online banking is cheaper for banks, and it’s good at delivering some basic services. But it’s less good for the kind of meaningful banking activity the CRA was meant to encourage. And that goal of the CRA is precisely what regulators now seem poised to water down.